ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Effect of early intervention in an interdisciplinary

group of children with Down syndrome in a special integration center

Efeito da estimulação precoce em grupo

interdisciplinar de crianças com síndrome de Down em um centro de integração

especial

Renata Pianezzola de

Oliveira*, Daniela Azambuja Ilha**, Carolina Maria Mugnol**, Rejane

Terezinha Gonçalves Conceição***, Sílvia Bitencourt****, Viviane da Silva

Machado*****, Laís Rodrigues Gerzson******, Carla Skilhan de

Almeida, D.Sc.*******

*Fisioterapeuta,

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre/RS,

**Fisioterapeuta, Kinder - Centro de Integração da Criança Especial,

Porto Alegre/RS, ***Fonoaudióloga, Kinder - Centro de Integração da

Criança Especial, Porto Alegre/RS, ****Psicóloga, Kinder - Centro de

Integração da Criança Especial, Porto Alegre/RS, *****Terapeuta

Ocupacional, Kinder - Centro de Integração da Criança Especial,

Porto Alegre/RS, ******Fisioterapeuta, Doutoranda do Programa de Pós

graduação Saúde da Criança e do Adolescente da Universidade Federal do Rio

Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre/RS, *******Fisioterapeuta, Docente do Curso

de Fisioterapia da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS),

Porto Alegre/RS

Received: April 20,

2018; Approved: August 9, 2018.

Corresponding

author:

Carla Skilhan de Almeida, Rua Felizardo, 750 Jardim Botânico 90690-200 Porto

Alegre RS, E-mail: carlaskilhan@gmail.com; Renata Pianezzola de Oliveira:

pianezzola.re@gmail.com; Daniela Azambuja Ilha: reabilitação@kinder.org.br;

Carolina Maria Mugnol: carolinamugnol@yahoo.com.br; Rejane Terezinha Gonçalves

Conceição: rejanifono@hotmail.com; Sílvia Bitencourt:

bitencourtsilvia@hotmail.com; Viviane da Silva Machado: vivica2608@gmail.com;

Laís Rodrigues Gerzson: gerzson.lais@yahoo.com.br

Abstract

Objective: To verify the

effects of early stimulation on the motor and cognitive development of children

with Down syndrome taking part of an interdisciplinary early stimulation group at

a Special Child Integration Center. Methods:

Prospective Observational Study carried out at a Special Child Integration Center

with children from 0 to less than 1 year of age, taking part of an early stimulation

group and who were not participating in any other intervention. Children included

were evaluated in the rehabilitation sector of the institution. The instrument used

was the Child Behavior Development Scale and the data were presented descriptively

with percentage based on the answers of individual behavior and on the group average

pre- and post-intervention. Results: The

group was homogeneous regarding the characteristics and possible factors associated

to developmental delay. In the motor and cognitive performance, individually all

children had an improvement on their performance equal or greater than 50% in comparison

to the initial assessment, and the group had a 62.5% growth in comparison to the

initial evaluation. Conclusion: In group

early stimulation brings benefits on the motor and cognitive development of children

with Down syndrome in interdisciplinary care.

Key-words: early stimulation,

child development, Down syndrome.

Resumo

Objetivo: Verificar os efeitos

da estimulação precoce sobre o desenvolvimento motor e cognitivo de crianças com

síndrome de Down que participam do grupo interdisciplinar de estimulação precoce

oferecido em um Centro de Integração da Criança Especial. Métodos: Estudo observacional prospectivo. Foi realizado em um Centro

de Integração da Criança Especial com crianças de zero a um ano incompleto, que

estivessem participando do grupo de estimulação precoce e que não participassem

anteriormente de outra intervenção. As crianças incluídas foram avaliadas no setor

de reabilitação da instituição. O instrumento utilizado foi a Escala do Desenvolvimento

do Comportamento da Criança e os dados foram apresentados de forma descritiva com

percentual baseado nas respostas do comportamento individual e da média do grupo

pré e pós-intervenção. Resultados: O grupo foi homogêneo em relação às características e possíveis

fatores associados ao atraso do desenvolvimento. No desempenho motor e cognitivo,

individualmente todas as crianças obtiveram um crescimento em seu desempenho igual

ou superior a 50% comparado com a avaliação inicial e o grupo obteve crescimento

de 62,5% comparado com a avaliação inicial. Conclusão:

A estimulação precoce em grupo traz benefícios sobre o desenvolvimento motor e cognitivo

de crianças com síndrome de Down em atendimento interdisciplinar.

Palavras-chave: estimulação precoce,

desenvolvimento infantil, síndrome de Down.

Introduction

Early childhood, from birth to three years of age, is marked by an accelerated

growth rate [1]. Infant motor development is characterized by the child’s motor

acquisitions, from the simpler to the more complex, which allow a wide and precise

succession of movements and interaction with her/his environment [1,2]. Such changes

are intrinsically related to the interactions within the subject and also interactions

between the subject, the environment and the proposed task [2]. In this period,

movement is extremely important for the child’s cognitive development, and such

experiences offered to the child can positively influence the development of his/her

motor skills [3].

However, there are many factors which can compromise child development, such

as biological risks – which affect prenatal development and usually are associated

with gestation and birth conditions; environmental risks – which include the aspects

related to deficient family structure and inadequate stimulation [3]. Other factors,

such as prematurity and low birthweight and inborn errors

of metabolism are also found in the literature as being responsible for a higher

risk for deficits in neuropsychomotor development. Thus,

the child can present learning difficulties, problems with language, social interaction

and motor coordination [4,5]. Down syndrome (DS), a genetic

condition with specific physical and mental characteristics, also leads to neuropsychomotor developmental delay. In the realm of motor

activities, children with DS reach basic motor milestones at slower times than children

with normal development and, from the cognitive point of view,

the language area is highly compromised [6].

Given the importance and impact of developmental delay, early identification

of infants at risk is vital to minimize the consequent effects [7]. Each child has

her/his own characteristics, that is, s/he is an individualized being, and genetic

and environmental factors influence her/his neuropsychomotor

development. Therefore, the treatment shall consider the individuality of each child,

as well as the familiar context in which s/he is inserted [8]. The main goal of

the Physical Therapy intervention is to stimulate motor development, in association

with the acts initiated by the child herself/himself, encompassing her/his neuropsychomotor aspects and the context in which s/he lives

[8].

In light of such reality, the Early Intervention Program (EIP) exists as

part of the special education realm and targets children with special needs from

birth to three years of age [9]. The EIP consists of a set of encouraging activities

designed to provide the child with meaningful experiences, aiming at reaching the

full development of her/his evolutionary process [10]. The EIP also consists of

planning specific psychomotor activities, respecting the age group and encouraging

the child to interact in the environment without threating her/his freedom of expression

[11]. Thus, it is important to stress that the EIP’s role is not to make the child

a typical one, but to make up for the deficiencies and their effects [10]. With

that, the EIP’s main goal has been to minimize, remedy or prevent, through actions,

the adverse effects of the development of children with disabilities [9].

The human being is an integral individual that requires a care which understands

her/his integrality, which meets her/his biopsychosocial

needs. Thus, interdisciplinarity is fundamental because

it allows for a new configuration of health knowledge and a new way to provide health

[12]. Therefore, health is viewed as interdisciplinary, so, health professionals

need to be ready and committed to the reality of health. In addition to that, they

must be willing to share their knowledge to attain a common goal [13].

Hence, the objective of this study was to determine the effects of early

intervention on the motor and cognitive development of children with Down syndrome

who participated in an early intervention interdisciplinary group offered at a Special

Child Integration Center.

Methods

Sample

This study had a quasi-experimental design and was devised according to the

guidelines and regulatory norms for research involving human beings, presented to

the Ethics and Research Committee and approved under No. 1.009.551, with the participation

of 6 children of the Early Intervention Program First Steps at Kinder - Special

Child Integration Center. The sample was intentional, with infants between 4 and

7 months of age. All children who participated in the study met the following inclusion

criteria: 1) were under one year of age; 2) did not participate in any other intervention.

The parents/guardians of each child were previously informed about the collection

procedures and signed a Free and Clarified Consent Term (FCCT).

Instruments

The children included in the study were assessed in the rehabilitation sector

at Kinder - Special Child Integration Center, located in Porto Alegre, the capital of the State of Rio Grande do Sul. Each participant was assessed by the same trained researcher,

who used the Child Behavior Development Scale in the First Year of Life [14]. The

collection happened in two moments and was carried out with the presence of the

person responsible for the child in a room with a tatami and the materials composing

the assessment kit. Thus, the first assessment happened at the beginning of the

program and, the second one, four months later.

This scale allows the assessment of an infant’s development in 64 behaviors

distributed month to month and in different age groups. This scale presents motor,

cognitive and social behaviors, which can be axial or appendicular; stimulated or

spontaneous; communicative or non-communicative. The axial motor behavior was designated

as motor organization related to posture, equilibrium and movement and sound emission;

the appendicular motor behavior was designated as organization in skills and dexterity,

encompassing manual, hearing and visuomotor coordination.

The classification of stimulated or spontaneous motor behavior was associated

to a specific stimulation, such as sounds and verbal communication, or a non-specific

one, triggered by the child’s position and environmental stimuli; such classifications

indicated the motor behavior.

As for the communicative or non-communicative, exteriorization in relation

to the child’s interaction with other people was observed, indicating the activity

behavior. Hence, the instrument was divided into eight subscales: Axial Spontaneous

Non-Communicative (fifteen activities of movement and posture); Axial Spontaneous

Communicative (eight activities of sound emission and repetition); Axial Stimulated

Communicative (five activities of body games and interaction with the examiner);

Appendicular Spontaneous Non-Communicative (eleven activities of perceiving and

manually exploring objects); Appendicular Spontaneous Communicative (one activity

of interaction with the researcher); Appendicular Stimulated Non-Communicative (eight

activities of handling and recognition of object function) and Appendicular Stimulated

Communicative (nine activities of task completion on request) [15].

Procedures

The interventions took place once a week with the presence of a family member/responsible

for the child during four months, according to the proposal offered by the institution,

with each session lasting one hour and twenty minutes. The Early Intervention Program

First Steps proposes group sessions with an interdisciplinary intervention model.

The professionals who work in that institution and are part of the program involve

a physical therapist, a psychologist, a speech therapist and an occupational therapist.

The professionals work in pairs, with physical therapy being matched with psychology

and occupational therapy with speech therapy, alternating their actions in the groups

fortnightly. The physical therapist guides the child’s proper positioning at home

and explains the stages of development; teaches movements to facilitate postural

changes and improve postural control (head and trunk); makes referrals, performs

exams and requests lower limbs orthoses. The psychologist

stimulates mother-infant bond, interaction among children, child’s acceptance, and

interaction and integration of the families; establishes group routines and gives

attention to the necessities of each family and helps build up a support network

for the families.

The speech therapist guides the positioning when eating, watches out for

food consistency, daily utensils and oral hygiene, makes exercises to facilitate

eating and communication; stimulates language – comprehension and speaking – and

observes hearing alteration and/or loss. The occupational therapist guides the positioning

to facilitate the use of the upper limbs to play, eat and do other daily activities;

indicates the adequate toy for each age group, helps with clothing, shower and makes

visual stimulation; requests furniture to keep the sitting position and hand orthoses; adapts utensils – cutlery, pencil, baby bottle, wheelchair

– and provides the infants with sensory and motor experiences to stimulate functionality.

The program aims at providing the families, in addition to the stimulation of their

children, with a moment of exchange of experiences, stories, fears and hopes, bringing

them closer and creating a support network for them.

At the end of this period, a reassessment was scheduled to carry out a new

collection, just like the first assessment.

Data analysis

Motor and cognitive development was assessed through the Child Behavior Development

Scale and the data are presented descriptively with percentage based on the responses

of the individual behavior and the group average pre- and post-intervention. To

that, a score from one to five was given to classify the child: with delay, at risk,

regular, good and excellent, respectively.

Results

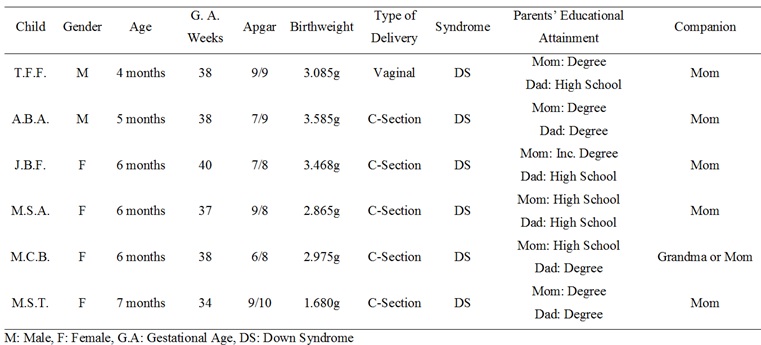

Six children with Down syndrome participated in the study, being two boys

and four girls, with ages between four and seven months (the mean age was 5.67 months).

Only one child was born preterm (gestational age ≥ 36 weeks) and with low

birthweight (≥ 2.500g). However, for the assessment,

her/his age was corrected. In relation to the Apgar score, none of the infants had

a score lower than 7 in the fifth minute, and no operative vaginal delivery was

performed, therefore, all babies were delivered either vaginally or by C-section.

As for the parents’ educational attainment, all of them had high school or a degree.

In terms of housing conditions, all children lived in proper places with water and

power supplies and sanitation. All children were accompanied by their mothers during

the intervention period (Table I).

Table I - Characteristics and possible factors associated

with developmental delay.

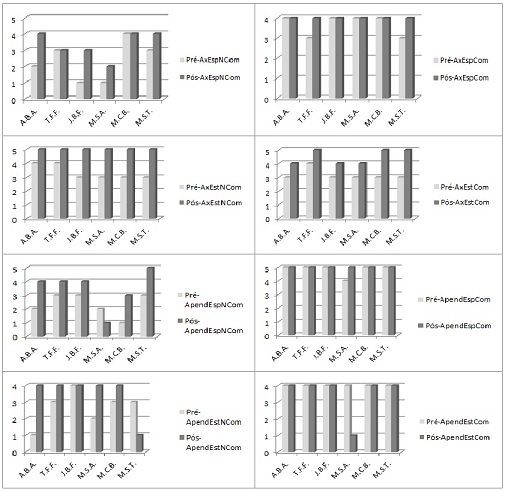

Figure 1 displays pre- and post-intervention results distributed into eight

subscales. The data indicate that participant A.B.A boosted his performance in five

out of eight subscales (62.5%), improving on the items related to posture and movement;

auditory reaction and visual sensitivity; body games and interaction with the examiner;

perception and manual exploration of objects; handling and recognition of object

function. As for the sound emission and repetition activities; interaction with

other people and task completion on request, it was noted that the child kept the

same classification pre- and post-intervention.

The participant T.F.F. boosted his performance in five out of eight subscales

(62.5%), improving on the items related to sound emission and repetition; auditory

reaction and visual sensitivity; body games and interaction with the examiner; perception

and manual exploration of objects; handling and recognition of object function.

He kept the same classification in the activities related to movement and posture;

interaction with other people and task completion on request.

The participant J.B.F. boosted her performance in four out of eight subscales

(50%), improving on the items related to posture and movement; auditory reaction

and visual sensitivity; body games and interaction with the examiner; perception

and manual exploration of objects, while keeping the classification in sound emission

and repetition; interaction with other people; handling and recognition of object

function and task completion on request.

The participant M.S.A. boosted her performance in five out of eight subscales

(62.5%), improving on the items related to posture and movement; auditory reaction

and visual sensitivity; body games and interaction with the examiner; interaction

with other people and handling and recognition of object function, while keeping

the same classification in the activities related to sound emission and repetition

and having a decrease in perception and manual exploration of objects and task completion

on request.

The participant M.C.B. boosted her performance in four out of eight subscales

(50%), improving on the items related to auditory reaction and visual sensitivity;

body games and interaction with the examiner; perception and manual exploration

of objects and handling and recognition of object function, while keeping the same

classification in the activities related to posture and movement; sound emission

and repetition; interaction with other people and task completion on request.

The participant M.S.T. boosted her performance in five out of eight subscales

(62.5%), improving on the items related to posture and movement; sound emission

and repetition; auditory reaction and visual sensitivity; body games and interaction

with the examiner; and perception and manual exploration of objects, while keeping

the same classification in the activities involving interaction with other people

and task completion on request and having a decrease in the activities related to

handling and recognition of object function.

As for the group, the results suggest that the post-intervention performance

has significantly progressed in comparison to the initial period in five out of

eight subscales (62.5%) in the activities related to posture and movement; auditory

reaction and visual sensitivity; body games and interaction with the examiner; perception

and manual exploration of objects; and handling and recognition of object function.

The group did not get any increase or decrease in the activities related to sound

emission and repetition; interaction with other people and task completion on request.

Figure 1 – Pre- and post-intervention assessment results.

Discussion

The results are favorable concerning physical environment and family structure,

because virtually all children came from structured families who had good housing

conditions. Studies point to peculiar issues related to the physical structure of

the house and the external environment in which the child is inserted as factors

which can help or harm her/his development, as well as the interpersonal relations

and the roles played by the family members [16]. Low-stimuli environments can negatively

interfere, that is, the place in which the baby lives offers different formats or

shapes aspects of her/his behavior [17]. Thus, the context in which the child is

inserted, including social interactions and family environment, influences either

positively or negatively both skill acquisition and functional independence [1,3,17,18].

This study wanted to determine the effects of early intervention on the motor

and cognitive development of children with Down syndrome who currently participate

in an early intervention interdisciplinary group offered at a Special Child Integration

Center. Studies provide evidence on the characteristics of the motor and cognitive

development of children with Down syndrome. When developing motor skills, studies

indicate that this public presents a delay in basic motor milestones, which manifest

at slower times than children with typical development, and cognitive developmental

delay stems from the symptom manifestation of this genetic condition [6]. It is

also seen in the literature that motor deficits are predominant in early childhood,

whereas cognitive deficits are predominant at school age [6]. A study which evaluated

the functional performance of children with Down syndrome in relation to the performance

of children with typical development (with average age of 5-7½ years) suggests that,

as the child with delay is acquiring skills, these are incorporated in her/his daily

life and, consequently, they will increase her/his independence [19].

The intervention proposed by the institution recommends interdisciplinary

and group care to provide the children and their families with a thorough follow-up.

We find in the literature the bases to structure this kind of intervention regarding

the organization and the way to provide care. Thus, the work of early stimulation

must be structured so as to welcome the child and her/his family. Regarding integrality,

professionals need a broader view of health, including their different forms of

production and the users’ perception of their biopsychosocial

totality. The professional must listen the user attentively, receive her/him in

a humanized way, using adequate answers, and then becoming responsible, generating

links, humanization, care and welcoming, actions which can contribute to the construction

of integrality. The professionals must understand the context of people and identify

assistance, prevention and health promotion needs, hence exchanging knowledge among

professionals [20].

Therefore, the care should be weekly, lasting between twenty and forty minutes

for individual care, and between one hour and one hour and forty minutes in groups.

Family members play a fundamental role in this context and need to receive the due

support and necessary orientations from the professionals involved to ensure the

continuity of the treatment at their homes [10]. The materials and physical spaces

should also be taken into account, with the former being suitable for each age group,

and the latter ventilated and adapted to the child’s needs [10,21]. The team of professionals must be willing to play an active

part in the intervention processes, take part in triage and assessment processes,

as well as provide the families with orientation and information for the program’s

full implementation [10]. The child with Down syndrome presents deficiency in the

motor, cognitive, sensory and vestibular system, thus, the treatment with an interdisciplinary

team is vital, since the therapies complement each other [22]. There is also the

possibility of a single therapist, in case there is not any multidisciplinary team

available, but such professional must pay attention to all the child’s needs and

not stick to the knowledge field of her/his speciality

[10].

Motor performance, which is addressed in the activities related to posture

and movement; auditory reaction and visual sensitivity; body games and interaction

with the examiner; perception and manual exploration of objects and handling and

recognition of object function had the highest growth when comparing pre- and post-intervention

results. It is believed that, in this case, the early stimulation program has allowed

for the integration of multiple systems and, therefore, made it easier for the children

to reach such motor milestones more rapidly. A study concluded that children who

received in group motor intervention showed a dramatic increase in their basic motor

skills, such as lying down and rolling, crawling and kneeling, in comparison to

children who only received individual training [23]. In a systematic review of the

motor performance of children with Down syndrome, it has been found that early intervention

can be used to reach motor milestones more rapidly, mainly in gait, and that such

positive response in motor performance is fundamental to the child’s integral development

[24].

It is noted that the activities related to sound emission and repetition;

interaction with other people and task completion on request kept the same classifications.

These activities address areas concerning language/cognition. In regard to the activities

of task completion on request, that is, to stop the activity when asked to, to clap,

to stroke and to reply to the request to hand objects in, these are behaviors which

usually appear at the end of the third trimester of life and normalize and stabilize

in the fourth trimester [14]. It is possible to infer, from this, that the children

were not able to perform such activities because, in the second assessment, most

of them were at the end of the second trimester of life. Our results corroborate

the findings of another study on motor performance, coordination and language which

observed that language had the lowest scores than the control group and that such

developmental area is the most compromised in children with Down syndrome [25,26].

It is widely known that the three first years of a child are crucial, because

her/his brain potentialities are fully developing. It is fundamental to provide

children with a welcoming and appropriate environment, to create strong bonds with

their careers, thus forming the bases for a full development [27].

Conclusion

In group early stimulation has brought benefits on the motor and cognitive

development of children with Down syndrome in a Special Child Integration Center.

It should be noted that this study has some limitations, such as the small number

of children assessed and the absence of a control group. Despite these limitations,

this study has raised pertinent issues concerning the interdisciplinary care of

children with Down Syndrome aiming at their full development.

References

- Illingworth RS. The development of the

infant and the young child: Normal and abnormal. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013

- Palma MS, Pereira BO, Valentini NC. Guided play and free play in an enriched environment:

Impact on motor development. Motriz: Revista de Educação Física 2014;20(2):177-85.

- Ammar D, Acevedo GA, Cordova A. Affordances

in the home environment for motor development: a cross-cultural study between American

and Lebanese children. Child Dev Res

2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/152094

- Caçola P, Bobbio

TG. (2010). Low birth weight and motor development outcomes: the current reality.

Rev Paul Pediatr 2010;28(1):70-6.

- Gallahue DL, Ozmun JC, Goodway JD. Compreendendo

o desenvolvimento motor-: bebês, crianças, adolescentes e adultos.

Porto Alegre: AMGH; 2013.

- Martin GE, Klusek J, Estigarribia B, Roberts

JE. Language characteristics

of individuals with Down syndrome. Topics in Language Disorders 2009;29(2):112.

- Saccani R, Valentini NC. Cross-cultural analysis of the motor development of Brazilian, Greek and

Canadian infants assessed with the Alberta Infant Motor Scale. Rev Paul Pediatr 2013;31(3):350-8.

- Saccani R, Valentini NC, Pereira KR, Müller AB, Gabbard

C. Associations of biological factors and affordances in the home with infant motor

development. Pediatr Int 2013;55(2):197-203.

- Bolsanello

MA. Interação mãe-filho

portador de deficiência: concepções e modo de

atuação dos profissionais em estimulação

precoce [Dissertation]. São Paulo: Universidade de São

Paulo; 1998.

- Brasil.

Diretrizes Educacionais

sobre Estimulação Precoce. In: Ministério da

Educação: Organização das

Nações Unidas

para a educação, a ciência e a cultura. Brasília: MEC/

Unesco; 1995.

- Nair MKC, Resmi VR, Krishnan R, Nair GH, Leena ML, Bhaskaran D et al. CDC Kerala 5: developmental

therapy clinic experience–use of child development centre

grading for motor milestones. Indian J Pediatr 2014;81(2):91-8.

- Farias Brehmer

LC, Souza Ramos FR. O modelo de atenção à

saúde na formação

em enfermagem: experiências e percepções.

Interface-Comunicação, Saúde,

Educação

2016;20(56).

- Silva TRD, Canto GDL.

Dentistry-speech integration:

the importance of interdisciplinary teams formation. Revista CEFAC 2014;16(2):598-603.

- Pinto EB, Vilanova LC.

O desenvolvimento do comportamento da criança no primeiro ano de vida: padronização

de uma escala para a avaliação e o acompanhamento. Casa do Psicólogo; 1997.

- Almeida CS, Valentini NC, Lemos CXG. (2006). A influência de um programa

de intervenção motora no desenvolvimento de bebês em creches de baixa renda. Temas Desenvolv 2006;14(83/84):40-48.

- Souza ESD, Magalhães LDC. Motor and functional

development in infants born preterm and full term: influence of biological and environmental

risk factors. Rev Paul Pediatr 2012;30(4):462-70.

- Miquelote AF, Santos DC, Caçola PM, Montebelo MIDL, Gabbard C. Effect of the home environment on motor and cognitive

behavior of infants. Infant Behav Dev

2012;35(3):329-34. http:// doi:

10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.02.002

- Sgandurra G, Bartalena L, Cioni G, Greisen G, Herskind A, Inguaggiato E, et al.

Home-based, early intervention with mechatronic toys for preterm infants at risk

of neurodevelopmental disorders (CARETOY): a RCT protocol. BMC Pediatrics 2014;14(1):268.

- Martins MRI, Fecuri MAB, Arroyo MA, Parisi MT. Evaluation of functional skills and self care of Down's syndrome people included in therapeutic

workshop. Revista

CEFAC 2013;15(2):361-5.

- Sanchez HF, Werneck MAF,

Amaral JHL, Ferreira EF. Integrality in everyday

dental care: review of the literature. Trab Educ

Saúde 2015;13(1):201-14.

- Frônio JDS, Silva LMDA, Gonçalves

RJ, Chagas PSDC, Ribeiro LC. Influence of object position

on the frequency of manual reaching in typically developing infants. Fisioter Pesqui

2011;18(2):139-44.

- Edgin JO. Cognition in Down syndrome: a developmental cognitive neuroscience

perspective. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science 2013;4(3):307-17.

- Fiss ACL, Effgen SK, Page J, Shasby

S. Effect of sensorimotor groups on gross motor acquisition for young children with

Down syndrome. Pediatr Phys

Ther 2009;21(2):158-66.

- Bertapelli F, Silva FF, Costa LT,

Gorla JI. Desempenho motor de crianças com Síndrome de

Down: uma revisão sistemática. J Health Sci Inst 2011;29(4):280-84.

- Priosti PA, Blascovi-Assis SM, Cymrot

R, Vianna DL, Caromano FA. Grip strength and manual dexterity in Down Syndrome

children. Fisioter Pesqui 2013;20(3):278-85.

- Carvalho AMDA, Befi-Lopes DM, Limongi SCO. (2014, June).

Mean length utterance in Brazilian children: a comparative

study between Down syndrome, specific language impairment, and typical language

development. CoDAS 2014;26(3):201-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2317-1782/201420140516.

- Cunha AJLAD, Leite AJM,

Almeida ISD. The pediatrician's role in the first thousand days of the

child: the pursuit of healthy nutrition and development. J Pediatr

2015;91(6):S44-S51.