Fisioter Bras.

2023;24(2):153-65

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

High versus low frequency transcutaneous acupoint

electrical stimulation as an adjunct therapy to prevent nausea and vomiting in

the first 24 hours after infusion of high-grade emetic chemotherapy: a

randomized controlled trial

Estimulação

elétrica transcutânea de alta versus baixa frequência como terapia adjuvante

para prevenir náuseas e vômitos nas primeiras 24 horas após a infusão de

quimioterapia emética de alto grau: um estudo controlado randomizado

Rafael

Ailton Fattori1, Júlia Schlöttgen1, Fernanda Laís Loro1,

Pauline Lopes Carvalho1, Rodrigo Orso2, Fabricio Edler Macagnan1

1Universidade Federal de Ciências da

Saúde de Porto Alegre, RS Brasil

2Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio

Grande do Sul

Received: 2022,dec 22;

accepted 2023, feb 25.

Correspondence: Fabricio Edler Macagnan,

fabriciom@ufcspa.edu.br

How to cite

Fattori RA,

Schlöttgen J, Loro FL, Carvalho PL, Orso R, Macagnan FE. High versus low frequency transcutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation

as an adjunct therapy to prevent nausea and vomiting in the first 24 hours

after infusion of high-grade emetic chemotherapy: A randomized controlled

trial. Fisioter Bras 2023;24(2):153-65. doi: 10.33233/fb.v24i2.5136

Abstract

Background: Transcutaneous

acupoint electrical stimulation (TAES) has been tested as antiemetic therapy. Objective:

Evaluation of the effectiveness of two different frequencies of the electrical

current as adjunctive therapy in the prevention of nausea and vomiting. Methods:

This placebo-controlled clinical trial compared the incidence of nausea and

vomiting (within the first 24 hours after high-grade emetic chemotherapy

infusion) of 61 women (54 ± 11 years) with breast cancer undergoing three modes

of TAES: high frequency (HF:150 Hz), low frequency (LF:10 Hz), and placebo (P).

Electrodes were fixed at the acupuncture point PC6 and a symmetric bipolar

current (pulse width 200 µs) was applied in a single 30-minute session prior to

the start of chemotherapy infusion. All patients receive fixed antiemetic

treatment infusions (ondansetron 8 mg) and rescue medication instructions, if

necessary, according to the routine for infusions of cyclophosphamide

associated with anthracycline. Results: The incidence of nausea was 47%

in P, 45% in HF and 26% in LF. Although not significant, the intervention with

LF-TAES at PC6 acupoint reached relevant values in reducing the relative risk

of developing nausea (RR = 0.51; CI 95% = 0.18 to 1.44; p = 0.18) and a trend

toward improved reported well-being (p = 0.06) and a lower Edmonton Symptom

Rating Scale score (p = 0.08). The incidence of vomiting and the consumption of

rescue antiemetic doses were very similar between the groups. Conclusion:

New studies with LF and HF of TAES as adjuvant therapy for the prevention of

nausea and vomiting should be carried out to confirm this hypothesis.

Keywords: Antineoplastic combined

chemotherapy protocols; antiemetic agents; electrical stimulation therapy;

acupuncture.

Resumo

Introdução: A estimulação elétrica transcutânea em

pontos de acupuntura (TAES) foi testada como terapia antiemética.

Objetivo: Avaliar a eficácia de duas frequências diferentes de corrente

elétrica como terapia adjuvante para a prevenção de náusea e vômito. Métodos:

Este ensaio clínico controlado por placebo comparou a incidência de náusea e

vômito (nas primeiras 24 horas após a infusão de quimioterapia emética de alto

grau) em 61 mulheres (54 ± 11 anos) com câncer de mama em três modos de TAES:

alta frequência (HF:150 Hz), baixa frequência (LF:10 Hz) e placebo (P). Os

eletrodos foram fixados no ponto de acupuntura PC6 e uma corrente bipolar

simétrica (largura de pulso 200 µs) foi aplicada em uma única sessão de 30

minutos antes do início da infusão de quimioterapia. Todos os pacientes recebem

infusões fixas de tratamento antiemético (ondansetrona

– 8 mg) e orientação de uso de medicação de resgate, se necessário, conforme

rotina para infusões de ciclofosfamida associada à antraciclina.

Resultados: A incidência de náusea foi de 47% no P, 45% na HF e 26% na

LF. Embora não significativa, a intervenção com LF-TAES no ponto de acupuntura

PC6, alcançou valores relevantes na redução do risco relativo de desenvolver

náuseas (RR = 0,51; IC 95% = 0,18 a 1,44; p = 0,18) e tendência de melhora na

sensação de bem estar (p = 0,06) e pontuação mais baixa na Edmonton Symptom Rating Scale (p = 0,08).

A incidência de vômitos e o consumo de doses antieméticas

de resgate foram muito semelhantes entre os grupos. Conclusão: Novos

estudos com LF e HF de TAES como terapia adjuvante na prevenção de náuseas e

vômitos devem ser realizados para confirmar essa hipótese.

Palavras-chave: protocolos combinados de quimioterapia

antineoplásica; agentes antieméticos; terapia de estimulação elétrica;

acupuntura

Introduction

The Multinational Association of

Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) cites that nausea and vomiting incidence in

antineoplastic protocols that combine anthracycline with cyclophosphamide can

reach 90% [1], but antiemetic drugs can reduce this incidence to values close

to 50% [2]. Nevertheless, non-pharmacological techniques such as transcutaneous

electric nerve stimulation (TENS) were proposed as complementary therapies to

support in the control of nausea and vomiting in these patients [3,4] as well

during postoperative period [5,6,7].

The last meta-analysis that

evaluated the effect of electric stimulating a specific acupuncture point (PC6)

associated with antiemetic drugs showed that the association of these

interventions is more effective in preventing postoperative vomiting when

compared to the exclusive use of drugs (RR = 0,56, CI 95% = 0,35 to 0,91; 9

trials, 687 participants). This therapy combination was not effective for the

prophylaxis of nausea (RR = 0,79, CI 95% = 0,55 to 1,13; 8 trials, 642

participants), but there was a reduction in the necessity for antiemetic drugs

in the postoperative period (RR = 0,61, CI 95% = 0,44 to 0,86; 5 trials, 419

participants) [7].

The mechanisms of action were

studied in an animal model [8] and some clinical trials, conducted in cancer

patients, have measured the effect of electrical stimulation under different

isolated or associated acupuncture points that are traditionally used in the

treatment of nausea and vomiting [3,4,8,9,10,11]. In an overview, there are many

discrepancies between these studies, but the PC6 was the most frequently

acupuncture point mentioned. The clinical characteristics of the patients

allocated were quite variable. The interventions also expose a quite different

between treatment time, weekly frequency and duration of the session. The

parameters used in electrical stimulation showed important differences, such as

the frequency of the electrical pulse, which in some studies was applied high

frequency others low frequency. Another aspect observed in these studies is a

tendency to applied electroacupuncture by transcutaneous acupoint electrical

stimulation (TAES) to avoid the risk of infection, inherent to the invasive

procedures. The results showed a favorable effect of TAES for the management of

nausea and vomiting, but there are many variations in these responses and

important discrepancies between the protocols.

The frequency of the electric pulse

is one of the main variables that make up the electric current, but there is no

consensus on whether high or low frequency is more effective. On the other

hand, the rate of incidence for nausea and vomiting is treatment-depended. Some

anticancer protocols are classified as high-grade emetic chemotherapy (HEC).

One of the most used HEC protocols combines anthracycline with

cyclophosphamide. This combination can induce nausea and vomiting up to 90% in

the first 24 hours after the infusion [12] and this specific characteristic

induced by the pharmacological association of the antineoplastic protocol

frequently used in the treatment of breast cancer, may be appropriate as a

clinical trial model to study antiemetic agents. Therefore, this study aims to

evaluate the acute effect of two frequencies of TAES on the incidence of nausea

and vomiting in volunteers undergoing a fixed regimen of HEC associated with

antiemetics usually prescribed in the care service.

Methods

This randomized, placebo-controlled

clinical study was conducted at the chemotherapy outpatient clinic after

approval by the local ethics committee (CAAE: 07489019.8.0000.5335) and

registered on the clinicaltrials.gov platform (NCT03145727). The study was

carried out in accordance with the ethical standards elaborated in the

Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and later amendments. Informed consent was

obtained from all individual participants included in the study (Form number:

3.265.023).

Sixty-one women (54 ± 11 years)

with breast cancer assigned to the HEC constituted by anthracycline combined

with cyclophosphamide were included. A fixed 8 mg ondansetron infusion (5-HT3

receptor antagonist) was administered prior to the chemotherapy session and

rescue doses of ondansetron and/or antihistamines and/or antidopaminergics were

instructed to use at home as needed. Only women with good functional capacity (Karnofsky score ≥ 70 points) and without previous (72

hours) nausea/vomiting symptoms were included. Patients with cognitive

limitations, undergoing concomitant radiotherapy, gastrointestinal and/or brain

metastases, cardiac pacemaker, or skin changes that did not allow electrical

stimulation to be performed were excluded.

Clinical evaluation

All participants received guidance

and training to record nausea and vomiting in the first 24h post-infusion of

HEC. The intensity/severity of nausea (visual analog scale 0-10) and vomiting

were recorded as recommended by the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO)

and the MASCC [12]. Home use of antiemetic drugs has been strictly controlled.

Telephone contact was maintained to answer questions and request form

(photographic) submission. The Edmonton Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS) was

incorporated into the form to control adverse symptoms [13].

Treatments

Eligible patients were randomized

into three groups: placebo (P); high frequency (HF) and low frequency (LF) of

the TEAS. An independent researcher used a random sequence generated at

randomizer.org to make opaque envelopes that were sealed and kept completely

confidential until the volunteers were assigned to one of the three

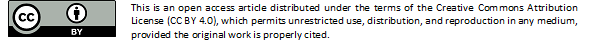

interventions. Neurodyn® III electro stimulator (Ibramed, Brazil) was applied 30-90 minutes before

chemotherapy. Reusable adhesive electrodes were positioned at the acupuncture point

PC6 on the contralateral infusion arm. One electrode was attached to two "tsuns" proximal to the flexion groove of the wrist in

the middle of the anterior surface of the forearm between the tendons of the

palmar muscles and radial flexors of the carpus, and the second electrode was

placed 5 cm above the CP6 towards the elbow (figure 1). For group P, the

electric current was adjusted with 75 Hz/200µs and intensity at the lower limit

of sensitivity. After 10 s, the intensity was reduced to zero, but the

electrodes were kept fixed for 30 minutes. In the LF and HF groups, the

currents were adjusted at the frequencies of 10 Hz and 150 Hz (respectively)

and both at the 200 µs pulse width. The stimulation time was 30 minutes and the

intensity was constantly increased to keep the

electric current at the upper tolerance limit.

Fig. 1 - The PC6 acupuncture point is

represented by the anatomical location demarcated by the first black circle

(1). The second black circle (2) indicates the position where the second electrode

was connected to complete the electrical circuit. The intervention by

transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TEAS) was performed in the arm opposite

to the chemotherapy infusion

Statistical analysis

An independent researcher used

Shapiro-Wilk, Fisher's exact, G (Williams), chi-square, relative risk (RR),

relative risk reduction (RRR), absolute risk reduction (ARR) to test the acute

effect of TEAS on the incidence of nausea and vomiting. Mann-Whitney was

conducted to analyze the intensity of nausea and vomiting as well the systemic

symptoms (ESRS) between interventions and placebo.

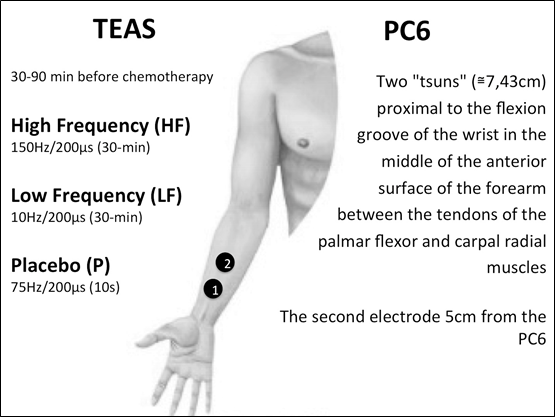

Fig. 2 - Study procedures flowchart

(CONSORT -2010)

Results

At baseline, 77 volunteers met the

eligibility criteria, but 75 patients agreed to participate in the study and

were randomized. However, only 61 completed and returned the nausea and

vomiting registering form (Figure 2). The total loss rate of the study sample

was 18%. There was homogeneity between the groups for age, type and phase of

chemotherapy cycles (Table I).

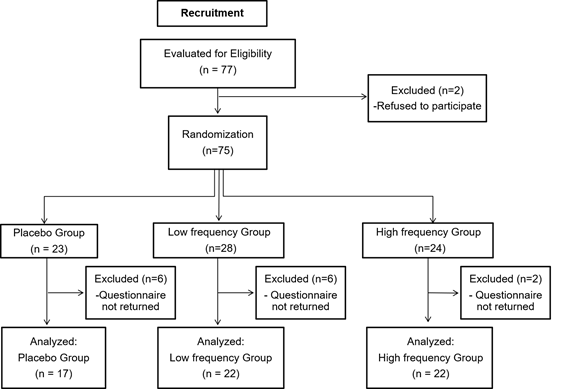

Table I - Clinical characteristics and

nausea symptoms and vomiting episodes in the first 24 hours after infusion of

high-grade emetic chemotherapy

The results were summarized using

values expressed in absolute terms and percentages, as well as mean and

standard deviation. The comparison between independent samples was performed

using Shapiro-Wilk, Chi-Square, G-test (Willians) and

Fisher’s exact tests

The incidence rate of nausea and

vomiting was statistically similar between groups. The total notifications of

nausea and vomiting were also similar between interventions. The same results

were found between interventions regarding the intensity of nausea symptoms.

Controlling the use of antiemetics in the domestic environment demonstrates

that the need for additional pharmacological management was very balanced

between interventions. The number of rescue doses of antiemetics was similar

between interventions, although the mean number of doses consumed in the LF and

HF groups represented 75% and 58%, respectively, of the mean number of doses

ingested in the placebo group.

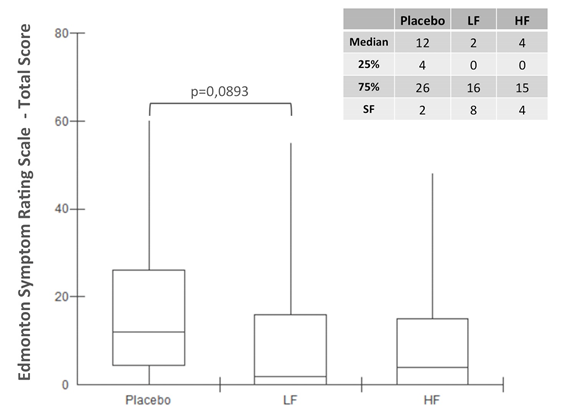

Fig. 3 - Edmonton Symptom Rating Scale

(ESRS) total score for placebo and low-frequency (LF) and high-frequency (HF)

TAES interventions. The box plot presents data through the median and maximum

and minimum values and interquartile range (25%-75%). The effect of LF and HF

was compared individually to placebo using the Mann-Whitney test. SF = symptom

free is the number of volunteers who remained asymptomatic during the first 24

hours after infusion of high-grade emetic chemotherapy

The relative risk of nausea was

very close between HF-TAES and placebo (RR = 0.97; p = 0.41; CI 95% = 0.49 to

1.91; RRR = 3%; ARR = 1.6%; NNT = 63), but when comparing LF-TAES with placebo,

the relative risk reduction was much more expressive. There is a high

probability of error in this estimation, but the magnitude of the relative risk

was substantially high (RR = 0.58; p = 0.17; CI 95% = 0.25 to 1.35; RRR = 42%;

ARR = 18%; NNT = 6).

The occurrence of symptoms assessed

by the ESRS was evenly distributed among the interventions (data not shown).

Symptom intensity was also equivalent between groups for pain, tiredness,

drowsiness, nausea, appetite, shortness of breath, depression and anxiety.

However, when compared to the placebo the LF-TAES showing a trend towards

improvement in the perception of well-being (p = 0.06) and in the total ESRS

score (p = 0.09) (Fig. 3). The number of volunteers who remain asymptomatic in

the first 24 hours after HEC infusion also tends to be smaller in the LF group

compared to placebo (RR = 0.72; p = 0.08; IC 95% = 0.50 to 1.03; RRR = 28%; ARR

= 24%; NNT = 5).

Discussion

TEAS applied to a unilateral PC6

acupuncture point, as proposed in this protocol, showed an uncertainly effect

in preventing nausea and vomiting in the first 24 hours after HEC infusion. The

incidence of nausea in placebo and HF-TAES interventions was proportionally

equivalent to the rates described by Roiola et al.

[12], but with a LF-TAES, there was almost half and, additionally, there was a

strong tendency to less intense manifestations. However, even with this

reduction in the proportion of the incidence of nausea, we cannot consider it

appropriate to attribute to LF-TEAS the effect of reducing the incidence of

nausea in the first 24 hours due to the high level of type I error observed.

The variability of the distribution reinforced the statistical requirement of

expanding the sample size. However, omitting this information would be an even

bigger mistake.

Nausea and vomiting can be

controlled by serotonin receptor inhibitors, antihistamines and

antidopaminergics [1,2] however, after cisplatin infusion, electroacupuncture

(applied to the acupuncture point VC12) showed lower plasma serotonin

concentration in animal [8]. This finding links the action of acupuncture's

antiemetic mechanism to state-of-the-art pharmacological therapies that involve

the serotonin-signaling pathway [14,15]. This connection between acupuncture

and pharmacological therapies became more unequivocal after the latest review

published by Lee et al. [7], PC6 acupoint stimulation was compared with

six different types of antiemetic drugs (metoclopramide, cyclizine,

prochlorperazine, droperidol, ondansetron and

dexamethasone), and no difference was found in the incidence of nausea (RR

0.91, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.10; 14 trials, 1.332 participants), vomiting (RR 0.93,

95% CI 0.74 to 1.17; 19 trials, 1.708 participants), or the need for rescue

antiemetic drugs (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.16; 9 trials, 895 participants).

The review included clinical trials that tested the effect of various types of

PC6 acupuncture point stimulation (acupuncture, electro-acupuncture,

transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation, transcutaneous nerve

stimulation, laser stimulation, capsicum plaster, acu-stimulation

device, and acupressure) as a way to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting

[5,6,7].

Another interesting result appeared

when Lee et al. [7] analyzed clinical trials that compared the effect of

PC6 stimulation combined with antiemetic drug and antiemetic drug alone. This

assessment showed that stimulation of acupuncture points as an adjunctive

therapy reduces the incidence of vomiting (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.91; 9

trials, 687 participants) and the necessity for rescue antiemetic drugs (RR

0.61, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.86; 5 trials, 419 participants) but not nausea (RR 0.79,

95% CI 0.55 to 1.13; 8 trials, 642 participants). Our findings have progressed

in a slightly different direction. The incidence of vomiting and the

consumption of rescue antiemetic doses were very similar between the groups,

but the few occurrences of vomiting made the analysis unfeasible.

Postoperative nausea and vomiting

are clinically distinct from chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting,

particularly when HEC is infused, but there is some

evidences that acupoint therapy could be useful to prevent nausea and vomiting

induced by chemotherapy [16,17]. In patients under chemotherapy for lung

cancer, the acupoint stimulation drastically decreased the nausea and vomiting

at Grade II-IV when compared to the control group (RR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.37-0.51;

P = 1E-5, 8 studies, 501 patients). In addition, increases in hemoglobin,

platelets and immunomodulatory response markers were also observed (increase of

IL-2, CD3+ and CD4+ T cells and NK cells) [18]. Some studies showed an

advantage in the improvement of performance status and quality of life

(EORCT-QLQ-C30) [19].

The overall score of the main

symptoms evaluated in our study showed a strong favorable trend for LF-TEAS.

The benefits of LF-TAES on cancer-related symptoms open an opportunity for

clinical studies on the effect of electro stimulation on the quality of life of

patients undergoing anticancer treatment. The feeling of well-being was the

best scored aspect by patients undergoing LF-TAES. In this sense, another

important finding was the substantial number of volunteers who remained

asymptomatic after the intervention with LF-TAES.

Nonetheless, our results indicate

the possibility that the frequency used in the TAES may have a relevant role in

the effects size of the intervention. This hypothesis was described before, but

Xie et al. [9] found no statistical

significant differences between placebo and low frequency (4Hz) applied under

multiple acupuncture points simultaneously stimulated (PC6, E36 and LI4; with

electrode patch placed on the skin surface, and intensity between 7-15 mA;

twice a day, for 30 min to 60 min by six consecutive days) combined with a

fixed dose of an antagonist of serotonin (palonosotron,

0.25 mg). The patients (active acupuncture, n = 72 or placebo acupuncture, n =

70) were followed for 5 days after cisplatin infusion (60 mg) and no significant

differences were found.

Interpersonal variations play an

important role in the development of anticancer chemotherapy-induced

nausea/vomiting. As described by McKeon et al. [10], chemotherapy side

effects worsen after the first infusion cycle. In this regard, it is worth

noting that 56% of the volunteers who participated in our study had completed

the first cycle of chemotherapy treatment. For prophylaxis purposes, evaluating

the effect of antiemetic strategies in volunteers free of cumulative effects is

the best scenario, but the interpersonal variations described in the literature

bring with them the need for studies with large samples, especially when the

incidence rate of symptoms is low, as observed in our study in relation to

episodes of vomiting. An interesting alternative would be to evaluate the

adjuvant effect of TAES in the management of nausea and vomiting in patients

who suffer recurrently from these disorders. Including only patients with

nausea and vomiting refractory to antiemetic therapies could be useful to

increase the accuracy of detection of the antiemetic effect of TAES. With more

occurrences of symptoms, the consistency of the adjuvant effects of TAES could

be explored in future clinical trials. In addition, the hypothesis of the

existence of other antiemetic action pathways of acupuncture could be tested.

On the other hand, we must consider

that the antiemetic mechanism of TAES is the same as that of some antiemetic.

Duplicating or intensifying the same antiemetic pathway may be ineffective in

preventing symptoms of nausea and vomiting, as this could be achieved simply by

increasing drug doses. Therefore, it is possible that TAES involves other

signaling pathways, but this hypothesis still needs to be confirmed. Our

results may be contributing to this possibility, whether the recommended dose

in routine cancer care is in fact the best dose established by the evidence

described in the literature.

Even though our results were

inconclusive due to intergroup variations and small sample size, this clinical

trial supports the possibility of using TEAS as an adjuvant therapy for the

management of undesirable effects of antineoplastic treatment and brings

additional information that reinforces the role of stimulation frequency in the

action pathway.

Conclusion

The results were inconclusive and

reinforce the need to increase the sample size. However, there is no evidence

to exclude the possibility of an antiemetic benefit from the use of TEAS as

adjunctive antiemetic therapy. Keeping the proportion of reduction in the

incidence of nausea observed in the intervention with LF-TEAS, it is perfectly

expected that in studies with larger sample sizes, this finding will indeed be

confirmed. The relevance of further studies is centered on the high number of

patients undergoing anticancer therapies who may benefit from this therapeutic

modality.

Acknowledgements

Eliane Goldberg Rabin, providing acupuncture knowledge support and article

review.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of

interest.

Study funding

This study was awarded the National

Multiprofessional Residency Scholarship Program of

the Ministry of Education of the Federal Government of Brazil, obtaining

financial support for conducting research in public health.

Authors' contributions

Concepção

e desenho da pesquisa:

Fattori RA; Macagnan FE; Obtenção

de dados: Fattori RA; Schlöttgen

J; Loro FL; Carvalho PL; Análise e interpretação dos dados: Fattori RA; Macagnan FE; Análise

estatística: Macagnan FE; Redação do

manuscrito: Fattori RA; Macagnan

FE; Schlöttgen J; Loro FL; Carvalho PL; Orso R; Revisão crítica do manuscrito quanto ao conteúdo

intelectual importante: Fattori RA; Macagnan FE

References

- Herrstedt J, Roila F, Warr D, Celio L, Navari RM, Hesketh PJ, Chan A, Aapro MS. 2016 Updated MASCC/ESMO Consensus

Recommendations: Prevention of Nausea and Vomiting Following High Emetic Risk

Chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2017 Jan;25(1):277-88. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3313-0 [Crossref]

- Rapoport B, Schwartzberg L, Chasen M, Powers D, Arora S, Navari R, Schnadig I. Efficacy and safety of rolapitant for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting over multiple cycles of moderately or highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2016 Apr;57:23-30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.023 [Crossref]

- Ozgür TM, Sandıkçı Z, Uygur MC, Arık AI, Erol D. Combination of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and ondansetron in preventiOzgür TM, Sandıkçı Z, Uygur MC, Arık AI, Erol D cisplatin-induced emesis. Urol Int. 2001;67(1):54-8. doi: 10.1159/000050945 [Crossref]

- Dou P-H, Zhang D-F, Su C-H, Zhang X-L, Wu Y-J. Electrical stimulation on adverse events caused by chemotherapy in patients with cervical cancer: A protocol for a systematic review of randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Feb;98(7):e14609. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014609 [Crossref]

- Lee A, Done ML. Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. The Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD003281. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub3 [Crossref]

- Lee A, Fan LT. Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD003281. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub3 [Crossref]

- Lee A, Chan SKC, Fan LTY. Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point PC6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2015(11):CD003281. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub4 [Crossref]

- Cui Y, Wang L, Shi G, Lui L, Pei P, Guo J. Electroacupuncture alleviates cisplatin-induced nausea in rats. Acupunct Med. 2016 Apr;34(2):120-6. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2015-010833 [Crossref]

- Xie J, Chen L-H, Ning Z-Y, Zhang C-Y, Chen H, Chen Z, et al. Effect of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation combined with palonosetron on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a single-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Chin J Cancer. 2017;36(6). doi: 10.1186/s40880-016-0176-1 [Crossref]

- McKeon C, Smith CA, Gibbons K, Hardy J. Electro Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture and no acupuncture for the control of acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a pilot study. Acupunct Med. 2015 Aug;33(4):277-83. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2015-010781 [Crossref]

- Chen B, Hu S, Liu B, Zhao T, Li B, Liu Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of electroacupuncture with different acupoints for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015 May;16:212. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0734-x [Crossref]

- Roila F, Herrstedt J, Aapro M, Gralla RJ, Einhorn LH, Ballatori E, et al. Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2010 May;21 Suppl 5:v232-43. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq194 [Crossref]

- Bruela E,

Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The

Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method of the assessment of

palliative care patients. J Palliat Care.

1991;2(7):6-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1714502/

- Herrstedt J. The latest consensus on antiemetics. Curr Opin Oncol. 2018 Jul;30(4):233-39. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000450 [Crossref]

- Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Chen G, Hong S, Yang Y, Fang W, Luo F, Chen X, Ma Y, Zhao Y, Zhan J, Xue C, Hou X, Zhou T, Ma S, Gao F, Huang Y, Chen L, Zhou N, Zhao H, Zhang Li. Olanzapine-based triple regimens versus neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist-based triple regimens in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with highly emetogenic chemotherapy: a network meta-analysis . Oncologist 2018 May;23(5):603-16. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0378 [Crossref]

- Ezzo J, Vickers A, Richardson MA, Allen C, Dibble SL, Issell B, Lao L, Pearl M, Ramirez G, Roscoe AJ, Shen J, Shivnan J, Streitberger K, Treish I, Zhang G. Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(28):7188-98. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002285.pub2 [Crossref]

- Ezzo JM, Richardson MA, Vickers A, Allen C, Dibble SL, Issell BF, Lao L, Pearl P, Ramirez G, Roscoe Ja, Shen J, Shivnan JC, Streitberger K, Treish I. Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD002285. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002285.pub2 [Crossref]

- Han JS. Acupuncture: neuropeptide release produced by electrical stimulation of different frequencies. Trends Neurosci. 2003 Jan;26(1):17-22. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)00006-1 [Crossref]

- Chen H-Y, Li S-G, Cho WC, Zhang Z-J. The role of acupoint stimulation as an adjunct therapy for lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013 Dec 17;13:362. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-362 [Crossref]