Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc 2020;19(4):312-321

doi: 10.33233/rbfex.v19i4.4007

REVIEW

Physical

exercise with aerobic predominance associated with blood flow restriction in

the elderly: is there enough evidence for its clinical application?

Exercício físico com

predominância aeróbia associado a restrição de fluxo sanguíneo em idosos: há

evidências suficientes para sua aplicação clínica?

Mariane Botelho Ferrari1,

Igor Covre Forechi1, Valério Garrone Barauna2, Leandro dos Santos3

1Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo,

Vitória, ES, Brazil

2Laboratório de Fisiologia Molecular, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo,

Vitória, ES, Brazil

3Unidade Acadêmica de Serra Talhada, Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Serra Talhada, PE, Brazil

Received

on: April 7, 2020; Accepted on: July 6, 2020.

Corresponding author: Leandro dos

Santos, Unidade Acadêmica de Serra Talhada, Universidade Federal Rural de

Pernambuco, Av. Gregório Ferraz Nogueira, S/N, José Tomé de Souza Ramos

56909-535 Serra Talhada PE, Brasil

Mariane Botelho

Ferrari: mariane_bferrari@hotmail.com

Igor Covre Forechi:

igorforechi@gmail.com

Valério Garrone Barauna:

barauna2@gmail.com

Leandro dos Santos:

leandro.santos79@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Physical exercise with aerobic predominance is already a known

strategy with benefits for the elderly population, and the use of blood flow

restriction (BFR) can be a promising and effective alternative to bring vaster

benefits with lower training loads when compared to physical exercise without

restriction. Objectives: To review the scientific literature regarding

the effects of aerobic physical exercise using blood flow restriction in the

elderly. Methods: Searches were performed in three databases (PEDro, Pubmed, and Scielo). As descriptors, the combination of the terms blood

flow restriction/KAATSU, endurance/aerobic/walking aged people/elderly was

used. Results: Eight articles were included in the review. Three studies

investigated muscle adaptations, two studies investigated aerobic capacity,

three studies addressed cardiovascular and hemodynamic responses, two articles

analyzed oxidative stress and hormonal responses, and one article assessed

physical function. Conclusion: Aerobic exercise in the elderly with BFR

seems to be superior to without BFR in this population. However, the low number

of studies does not allow a definitive conclusion. It should be noted that no

study has shown adverse effects or contraindications for the application of the

BFR.

Keywords: blood flow restriction; aerobic; elderly.

Resumo

Introdução: O exercício físico

com predominância aeróbia já é uma estratégia conhecida com benefícios para a

população idosa, e o uso da restrição de fluxo sanguíneo (RFS) pode ser uma

alternativa promissora e eficaz para trazer benefícios maiores com cargas de

treino menores, quando comparado ao exercício físico sem a restrição. Objetivos:

Revisar a literatura científica a respeito dos efeitos do exercício físico

aeróbico com uso da restrição de fluxo sanguíneo em idosos. Métodos:

Foram realizadas buscas em três bases de dados (PEDro,

Pubmed e Scielo). Como

descritores, foi utilizada a combinação dos termos blood

flow restriction/KAATSU, endurance/aerobic/walking aged people/elderly. Resultados: Foram incluídos oito artigos na

revisão. Três estudos investigaram adaptações musculares, dois estudos

investigaram a capacidade aeróbica, três estudos abordaram as respostas

cardiovasculares e hemodinâmicas, dois artigos analisaram o estresse oxidativo

e respostas hormonais, e um artigo avaliou a função física. Conclusão: O

exercício físico aeróbico em idosos com a RFS parece ser superior que o mesmo

realizado sem RFS nessa população. Entretanto, o baixo número de estudos

encontrado não permite uma conclusão definitiva. Deve-se ressaltar que nenhum

estudo mostrou efeitos adversos ou contraindicação para a aplicação da RFS.

Palavras-chave: restrição de fluxo

sanguíneo; exercício aeróbico; idosos.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines the elderly from their

chronological age, that is, elderly is any individual aged 60 or over in

underdeveloped countries, as is the case in Brazil [1]. According to the WHO,

by the year 2025, Brazil will be the sixth country in the world in the number

of elderly people, because of the increase in average life expectancy. Thus,

the quality of life of the elderly has been the subject of discussions for the

aspects that it involves and interferes with.

The regular practice of physical exercise reduces the risk of developing

chronic diseases, brings benefits to mental health and social integration.

According to the American College of Sports Medicine, long-term adaptive

responses in non-frail older adults are qualitatively like those seen in young

individuals. Although there may be a long time for adaptation, the elderly also

have benefits such as improved VO2max,

submaximal metabolic responses, exercise tolerance, muscle strength,

resistance, and hypertrophy when undergoing training [4].

Recently, interest in physical activity associated with blood flow restriction

(BFR) has grown. BFR consists of restricting part of the blood flow to a

specific limb by applying a cuff to the proximal portion of the upper or lower

limbs. This technique, also known as KAATSU, does not generate ischemic

conditions in the muscles, but an accumulation of blood in the capillaries,

making the flow turbulent [5].

The BFR as a viable strategy to be used in different sports practices

(walking, cycling, resistance exercises) has become an important topic of

study. BFR exercises have shown promising results in increasing muscle

strength, hypertrophy, cardiorespiratory, and muscle resistance. During

resistance training, results of muscle hypertrophy and increased strength are

observed like those of a high-intensity exercise but using a lower intensity

[6,7]. However, there are restrictions to BFR not directly linked to the aging

process, but specific circulatory diseases, hemodynamic or clinical issues.

Studies with aerobic predominance exercises associated with BFR bring

several chronic and acute adaptations in the general population. The acute

adaptations of this type of exercise with BFR are mainly the increase in energy

expenditure, oxygen consumption and increase in excessive oxygen consumption

after exercise (EPOC), increased intracellular signaling, and increased growth

hormone (GH). However, there is still no consensus specifying which is the best

protocol to be followed in the use of BFR with aerobic exercise for each

determined type of population. Therefore, this study aimed to review the

effects of aerobic exercise with the use of blood flow restriction in the

elderly [8].

Methods

In this study, there was a systematic narrative review of scientific

articles on the topic chosen. To conduct this study, articles published in the

databases Pubmed, PEDro,

and Scielo were selected, from January 2000 to May

2019, using the descriptors, in English: “blood flow restriction endurance

elderly”; “blood flow restriction endurance aged people”; “blood flow

restriction aerobic elderly”; “blood flow restriction aerobic aged people”; “kaatsu endurance elderly”; “kaatsu

endurance aged people”; “kaatsu aerobic elderly”; “kaatsu aerobic aged people”; “kaatsu

walking aged people”; “kaatsu walking elderly”.

Two researchers performed the searches

independently and compared the results found. A third researcher supervised the

selection and collaborated with the identification following the inclusion and

selection criteria. Subsequently, an analysis of the references of the selected

studies was carried out to identify other studies not included in the searches.

The exclusion criteria for this study were: studies not performed in the

elderly, literature review, studies addressing caloric restriction, studies

using animal models, and studies that did not perform aerobic exercise.

Results

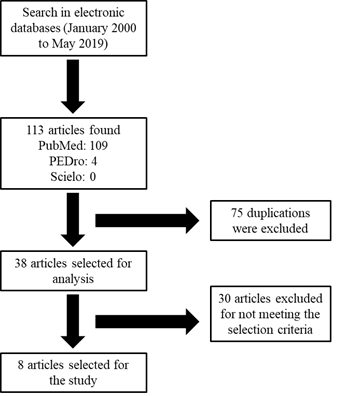

There were found 113 articles in the three selected databases. In

PubMed, 109 articles were found, in PEDro 4, and in Scielo, no study was found. Then, there were verified

duplications, 75 studies were excluded.

Thus, 38 articles were analyzed with information obtained through the

title and abstract. Eleven studies were identified as able to enter this work

and later read in their entirety, with only eight selected in the end. The flow

chart below summarizes the article selection process.

Figure

1 – Flow chart

The presentation of the results was performed, according to the study

outcome. Table I, at the end of the results, presents a summary of the studies.

Hypertrophy

and muscle strength

Regarding the increase in strength and hypertrophy, three studies

investigated the effects of aerobic exercise with BFR.

Libardi

et al. [9] concluded that muscle strength and hypertrophy increased

similarly after 12 weeks with both traditional concurrent training and that

associated with BFR. The only advantage observed in the groups with BRF was

that the total training volume was lower to obtain a result like the group

without BFR [9].

Abe et al. [10] concluded that walk training for six weeks

associated with BFR improves muscle strength and functional capacity in both males

and elderly females. The results showed that there were no significant changes

in body mass and body mass index for any of the groups. However, the group with

the BFR showed an increase in the perimeter of the thigh (5.8%) and the leg

(5.1%). The maximum isometric torque of knee extension increased (11.8%) in the

group with BFR. The same occurred with isokinetic knee extension and flexion,

which increased (7.1 to 12.2% and 13.4 to 16.1%, respectively) in the presence

of BFR. The only limitation of this study was that two participants did not

support the 200mmHg occlusion pressure due to the perception of muscle fatigue

during exercise with BFR [10].

The research by Ozaki et al. [11] concluded that walking with BFR

performed 4 times a week for 10 weeks was an effective strategy to promote

muscle hypertrophy and to increase the strength of knee flexors and extensors

in the elderly population. The results showed a better response in muscle

hypertrophy (3.2%), improvement in muscle strength of extensors (8.7%), and

knee flexors (15%) in the group with BFR when compared to the control group

[11].

Aerobic

capacity

Two studies investigated the effects of aerobic exercise with BFR on

aerobic capacity. The study by Libardi et al.

[9] found similar improvements in the cardiorespiratory capacity of both groups

(VO2 max increased from 9.5 to 10.3% with or without BFR) [9]. However,

the study by Abe et al. [10] found no increase in %VO2 max in any of the

groups, concluding that walking training with BFR for 6 weeks does not improve

cardiovascular fitness in the elderly [10].

Physical

function

Clarkson et al. [12] concluded that walking 4 times a week for 6

weeks at a speed of 4 km/h associated with BFR brings beneficial results to

improve physical fitness in sedentary elderly individuals. The results show

that the BFR group increased the number of repetitions performed during the

sitting and standing test in 30 seconds, compared to the group without BFR. The

other measures of physical function, such as distance covered in the 6-minute

walk test (6MWT), the time to complete the Timed Up and Go (TUG), and the steps

of the Queen's College Step Test (QCST), showed similar improvement in both

groups, with and without BFR [12].

The previously mentioned study by Abe et al. [10] also investigated the

functional capacity. The results show an increase of approximately 13% in the

TUG test and about 14% in the sitting and standing test in the BFR group [10].

Cardiovascular

and hemodynamic responses

Four of the selected studies aimed to investigate the cardiovascular and

hemodynamic responses of aerobic exercise with BFR in the elderly.

The study by Staunton et al. [13] demonstrated that the use of

BFR caused an increase in cardiac output (L/min: Rest: 4.2 ± 0.1 vs.

Post-exercise: 8.4 ± 0.4) and systolic blood pressure (mmHg: Rest: 123 ± 3 vs.

Post-exercise: 138 ± 3) in a similar way when BFR is absent. There was an

increase in heart rate (bpm: BFR: 92 ± 5 vs. CON: 86 ± 3), mean arterial

pressure (mmHg: BFR: 108 ± 3 vs. CON: 100 ± 2), and the double product (×103

bpm x mmHg: BFR: 12.3 ± 0.7 vs. CON: 11.0 ± 0.6) significantly higher after

exercise in the BFR group. The authors concluded that walking associated with the

use of BFR could be a viable alternative without overloading the cardiovascular

system in an exacerbated manner [13].

Ferreira et al. [14] conducted a study to evaluate the autonomic

cardiac effects and hemodynamic responses up to 30 minutes after aerobic

exercise with the use of BFR in the elderly. The BFR group showed a tendency to

reduce systolic blood pressure (mmHg: pre: 130 vs. post: 120) and diastolic

blood pressure (mmHg: pre: 70 vs. post: 66), mean blood pressure (mmHg: pre: 94

vs. post: 87). A reduction in the double product (bpm x mmHg: BFR: 8000 vs.

CON: 10100) was found when comparing the group with and without BFR 30 minutes

after exercise. A reduction in HR (bpm: BFR: 66 vs. CON: 80) was also found in

the post-exercise period. The authors concluded that low-intensity aerobic

exercise with BFR can generate autonomic and hemodynamic cardiac responses that

cause less cardiovascular stress in this population. This study shows the

safety, from the cardiovascular point of view, of performing the aerobic

exercise with 50% BFR occlusion pressure [14].

Barili et al.

[15] conducted a study to investigate the acute responses of the

cardiorespiratory system in low-intensity aerobic exercise with BFR in aged

women, however, hypertensive. The study demonstrated that there is a similar

increase in HR, SBP, and MAP in the group with BFR versus without BFR, even in

hypertensive aged people during exercise. The authors concluded that

low-intensity aerobic exercise (30% of VO2 max) associated with BFR

generates cardiovascular stress like high-intensity aerobic exercise (50% of VO2max)

[15].

Finally, the study by Ozaki et al. [11] observed an improvement

in arterial compliance in both groups (with and without BFR) with no significant

difference between them. This improvement in carotid artery compliance was

observed after ten weeks of walking with BFR [11].

Hormonal

responses and oxidative stress

Ozaki et al. [16] conducted a study to investigate the acute

effects of hormonal responses after walking with the use of BFR in the elderly.

The study demonstrated that the levels of norepinephrine, insulin, and growth

hormone (GH) were higher in the period immediately after exercise in the BFR

group [16].

The study by Barili et al. [15],

previously mentioned, also aimed to analyze oxidative stress in low-intensity

aerobic exercise. The study showed that in the BFR group, there was an increase

in the activity of antioxidant enzymes in the post-intervention period. Increases

in the damage markers caused by oxidative stress after exercise were found in

both groups with and without BFR in a similar way. The authors concluded that

in addition to cardiovascular responses, low-intensity aerobic exercise with

BFR in hypertensive aged women could trigger an increase in antioxidant enzymes

[15].

Table

I - Summary of articles according to the order of

appearance in the text. (ver Anexo em PDF)

Discussion

According to the review, aerobic exercise with BFR appears to be as

effective as a training alternative to improve cardiorespiratory fitness,

muscle strength, hypertrophy, and physical function in elderly individuals.

However, the effects still do not seem to be as superior to exercise without

BFR. Besides, one must observe the broad heterogeneity between the study

protocols. Among the 8 studies included, there are variations between acute and

chronic, in the intensity of occlusion pressure, in the control group, and

mainly in the results. However, one interesting point is that no study has had

results that contradict the application of the BFR in the elderly population.

Although there are possible side effects related to the inadequacy of the

utilization of the restriction, uses under strict protocols solve this issue.

The mechanisms that allow these adaptations include: local hypoxia;

recruitment of fast muscle fibers; increased metabolic acidosis time;

stimulation of metabolic receptors; change in the muscular contractile

mechanism and deformation of the sarcolemma; greater stimulation of the

fast-glycolytic pathway, production of reactive oxygen species and hyperemia

after removing the cuff. The study by Wenborn et

al. [17] examined 3 series of unilateral knee extension of low intensity

(30% of 1-RM) using BFR performed until failure. In the 3rd series, the

electromyographic activity of the group with BFR was significantly higher in

the eccentric phase when compared to the group that did not use the restriction

[17].

Metabolic responses are due to the metabolic stress that restriction of

blood flow promotes. Several studies have shown that ischemic and hypoxia

conditions in muscle induce a higher demand for ATP hydrolysis, increase

phosphocreatine depletion, and decrease pH. The

research by Suga et al. [18] concluded that during low-intensity exercise (20%

of 1-RM) associated with BFR, there was also higher metabolic stress when

compared to the same exercise without restriction.

Regarding muscle strength gain and hypertrophy, three studies were found

[9-11]. All of them detected an increase in strength or hypertrophy after the

period of exercise with aerobic predominance associated or not with resistance

exercises. In the study by Libardi et al. [9],

the volume of training with resistance exercise in the BFR group was lower than

the group without BFR, which is an advantage for the use of BFR as already

described by Sakamaki et al. [19]. In this

study, Sakamaki et al. [19] also found

improvement in muscle hypertrophy in the lower limbs (3.2%) of individuals who

performed low intensity walking on a treadmill associated with BFR. The study

by Abe et al. [10] showed that the practice of aerobic exercise with BFR

improves muscle parameters, such as isometric and isokinetic strength, compared

to the control group. However, since they compared only with the control group

that did not perform physical exercise, it is hard to compare results regarding

the addition of BFR. However, we highlight the favorable results found in this

study in a short period and with low-intensity exercises, such as the 11.8%

increase in maximal isometric torque of knee extension and isokinetic of knee

extension and flexion with an addition of 7.1% and 13.4%, respectively.

Regarding aerobic capacity, only the study by Libardi

et al. [9] observed a significant improvement in VO2max, but

with no difference between groups with and without BFR. This result may have

been positive due to the protocol adopted being aerobic exercises + resistance

exercises (concurrent training), while the study by Abe et al. [10] found no

difference in either group. In another study by Abe et al. [7], low-intensity

aerobic exercise (40% VO2max) with BFR was performed in young

adults, demonstrated an increase in VO2max in the BFR group (6.4%)

when compared to the group that performed aerobic exercise without restriction

(0.1%) [7]. Other studies have also observed an improvement in VO2max

in young adults who were walking with BFR [20].

According to the American College of Sports Medicine, for an adaptation

of the aerobic capacity of a healthy elderly individual, it is necessary to

carry out an exercise program using at least 60% of VO2max, ≥3

times a week with a minimum duration of 16 weeks [4].

As for physical function, the study by Clarkson et al. [12]

showed significant improvement in all the functional measures evaluated. The

gain was approximately 4 repetitions in the sitting and standing test, which

corresponds to 28% of the baseline value. The improvements obtained in this

study are even better than those in the study by Abe et al. [10], who found

gains of 13% and 14% in the functional measures of TUG and in the sitting and

standing test, respectively in the BFR group.

Regarding cardiovascular and hemodynamic responses, the four studies

[13-16] presented favorable results in their findings regarding the use of BFR.

The study by Cirilo-Sousa et al. [21] also found a reduction in BP, HR,

and DP after aerobic exercise associated with BFR, with results like the study

by Ferreira et al. [14]. The research by Kumagai

et al. [22] found an increase right after the most relevant exercises of

SBP, MAP, DBP, and HR during aerobic exercise associated with the use of BFR,

demonstrating a cardiac stimulus like that without BFR [22]. These data confirm

the findings in the studies by Staunton et al. [13] and Barili et al. [15]. From an autonomic cardiovascular point

of view, Ferreira et al. [14] justify the lower cardiovascular stress

due to the increase in parasympathetic reactivation that was found only in the

BFR group.

Conclusion

We can conclude that the use of BFR associated with aerobic exercise as

a training alternative for the elderly resulted in improved muscle strength,

hypertrophy, and physical function in elderly individuals. However, the

evidence about its real effect on the cardiorespiratory capacity of this

population is still unclear.

Finally, no study has shown adverse effects or contraindications for the

application of physical exercises associated with BFR in this population.

However, it is necessary to conduct new studies that seek results comparing

aerobic training with BFR versus without BFR in the elderly, given the low

number of studies and heterogeneous protocols. It is also important to

emphasize the importance of studies for the establishment of protocols with

safety criteria for the application of the method.

References

- Organização Mundial da

Saúde [homepage na internet]. Relatório Mundial de Envelhecimento e Saúde

[citado 2019 Out 9]. Disponível em:

https://www.who.int/eportuguese/countries/bra/pt/

- Instituto Brasileiro de

Geografia e Estatística. Projeção da população [citado 2018 Out 9]. Disponível

em: https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br

- Civinski C, Montibeller

A, Oliveira AL. A importância do exercício físico no envelhecimento. Revista da

UNIFEBE 2011;1(9):163-75.

- Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, Singh MAF, Minson CT,

Nigg CR, Salem GJ et al. Exercise

and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc

2009; 41(7):1510-30. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a0c95c

- Sato

Y. The history and future of KAATSU training. International Journal of KAATSU

Training Research 2005;1(1):1-5. https://doi.org/10.3806/ijktr.1.1

- Abe

T, Kearns CF, Sato Y. Muscle size and strength are increased following walk

training with restricted venous blood flow from the leg muscle, Kaatsu-walk training. J Appl Physiol

2006;100(5):1460-6. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01267.2005

- Abe

T, Fujita S, Nakajima T, Sakamaki M, Ozaki H,

Ogasawara R et al. Effects of low-intensity cycle training with restricted leg

blood flow on thigh muscle volume and VO2max in young men. J Sports

Sci Med 2010;9(3):452.

- Silva

JCG, Neto EAP, Pfeiffer PAS, Neto

GR, Rodrigues AS, Bemben MG et al. Acute and chronic

responses of aerobic exercise with blood flow restriction: a systematic review.

Front Physiol 2019;10:1239.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.01239

- Libardi

CA, Chacon-Mikahil MP, Cavaglieri CR, Tricoli V, Roschel H, Vechin FC et al. Effect of concurrent training with blood flow restriction in the

elderly. Int J Sports Med 2015;36(5):395-9.

https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1390496

- Abe

T, Sakamaki M, Fujita S, Ozaki H, Sugaya

M, Sato Y et al. Effects of low-intensity walk

training with restricted leg blood flow on muscle strength and aerobic capacity

in older adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther

2010;33(1):34-40.

- Ozaki

H, Miyachi M, Nakajima T, Abe T. Effects of 10 weeks walk training with leg

blood flow reduction on carotid arterial compliance and muscle size in the

elderly adults. Angiology 2011;62(1):81-6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003319710375942

- Clarkson

MJ, Conway L, Warmington SA. Blood flow restriction

walking and physical function in older adults: A randomized control trial. J

Sci Med Sport 2017;20(12):1041-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2017.06.013

- Staunton

CA, May AK, Brandner CR, Warmington

SA. Hemodynamics of aerobic and resistance blood flow restriction exercise in

young and old adults. Eur J Appl Physiol

2015;115(11):2293-2302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-015-3213-x

- Ferreira

MLV, Sardeli AV, Souza GV, Bonganha

V, Santos LDC, Castro A et al. Cardiac autonomic and haemodynamic

recovery after a single session of aerobic exercise with and without blood flow

restriction in older adults. J Sports Sci 2017;35(24):2412-20.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1271139

- Barili A, Corralo

VDS, Cardoso AM, Mânica A, Bonadiman

BDSR, Bagatini MD, et al. Acute responses of

hemodynamic and oxidative stress parameters to aerobic exercise with blood flow

restriction in hypertensive elderly women. Mol Biol Reports

2018;45(5):1099-1109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-018-4261-1

- Ozaki

H, Loenneke JP, Abe T. Blood flow-restricted walking

in older women: does the acute hormonal response associate with muscle

hypertrophy? Clin Physiol Funct

Imaging 2017;37(4):379-83. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpf.12312

- Takarada Y, Takazawa

H, Sato Y, Takebayashi S, Tanaka Y, Ishii N. Effects

of resistance exercise combined with moderate vascular occlusion on muscular

function in humans. J Appl Physiol

2000;88(6):2097-2106. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.2000.88.6.2097

- Suga

T, Okita K, Morita N, Yokota T, Hirabayashi

K, Horiuchi M et al. Intramuscular metabolism during low-intensity resistance

exercise with blood flow restriction. J Appl Physiol

2009;106(4):1119-24. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.90368.2008

- Sakamaki MG, Bemben M, Abe T. Legs and trunk muscle hypertrophy

following walk training with restricted leg muscle blood flow. J Sports Sci Med

2011;10:338-40.

- Park

S, Kim JK, Choi HM, Kim HG, Beekley MD, Nho H. Increase in maximal oxygen uptake following 2-week

walk training with blood flow occlusion in athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol 2010;109:591-600.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-010-1377-y

- Cirilo-Sousa

MS, Araújo JP, Freitas ED, Aniceto RR, Araújo VC,

Pereira PMG, et al. Acute effect of aerobic exercise with blood flow

restriction on blood pressure and heart rate in healthy young subjects. Motricidade 2017;13:17-24.

https://doi.org/10.6063/motricidade.12874

- Kumagai K, Kurobe, K, Zhong,

H, Loenneke, JP., Thiebaud

RS, Ogita F, et al. Cardiovascular drift during low

intensity exercise with leg blood flow restriction. Acta Physiol Hung 2012;99:392-9.

https://doi.org/10.1556/APhysiol.99.2012.4