REVIEW

Pathophysiology

of worsening lung function in COVID-19

Fisiopatologia da piora

da função pulmonar no COVID-19

Giulliano Gardenghi,

PhD1,2,3,4

1Scientific Coordinator

of Hospital ENCORE, Aparecida de Goiânia/GO

2Scientific Coordinator

of the CEAFI Faculty, Goiânia/GO

3Technical Consultant of

Lifecare / HUGOL – Burns Intensive Care Unit, Goiânia/GO

4Technical Consultant at São Cristóvão

Hospital and Maternity, São

Paulo/SP

Corresponding author: Giulliano

Gardenghi, Hospital ENCORE, Rua Gurupi, Quadra 25,

Lote 6 a 8 Vila Brasília 74905-350 Aparecida de Goiânia GO Brazil

E-mail:

ggardenghi@encore.com.br

Abstract

Introduction: The new coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) has emerged as the main

threats to global health since December 2019. Addressing part of the pulmonary

pathophysiology involved in the disease is important to help interested health

professionals better understand the different aspects of this complex

pathology. Aim: This article aims to present part of the

pathophysiological process involved in pulmonary complications associated with

Covid-19. Methods: An integrative literature review was carried out,

with articles published between 2019 and 2020, in the Google and PubMed

databases, using the following search terms: coronavirus, COVID-19, pulmonary

complications, pneumonia. Results: 6 articles were included, addressing

the proposed theme. Conclusion: The individual's infection with COVID-19

has the potential to cause significant changes in ventilatory capacity, leading

to diffuse pulmonary impairment and worsening gas exchange. Further studies are

needed to clarify the pathophysiology of this complex disease with a high

potential for contagion, morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: coronavirus

infections, communicable diseases, pneumonia.

Resumo

Introdução: A nova pneumonia por coronavírus (COVID-19) surgiu como as principais ameaças à

saúde global desde dezembro de 2019. Abordar parte da fisiopatologia pulmonar

envolvida na doença é importante para ajudar os profissionais de saúde

interessados a compreender melhor os diversos aspectos dessa complexa

patologia. Objetivo: Esse artigo tem o intuito de apresentar parta do processo

fisiopatológico envolvido nas complicações pulmonares associadas à Covid-19. Métodos:

Foi realizada uma revisão integrativa da literatura, com artigos publicados

entre 2019 e 2020, nas bases de dados Google e PubMed,

utilizando os seguintes termos para pesquisa: coronavirus,

COVID-19, complicações pulmonares, pneumonia. Resultados: Foram

incluídos 6 artigos, abordando o tema proposto. Conclusão: A infecção do

indivíduo pela Covid-19 tem potencial de causar alterações significativas na

capacidade ventilatória, cursando com comprometimento pulmonar difuso e piora

nas trocas gasosas. Mais estudos são necessários para esclarecer a

fisiopatologia dessa doença complexa com alto potencial de contágio, morbidade

e mortalidade.

Palavras-chave: infecções por coronavirus, doenças transmissíveis, pneumonia.

Introduction

COVID-19, or the coronavirus, started in

China in late 2019 as a set of cases of pneumonia with an unknown cause. The

cause of pneumonia was found to be a new virus - severe acute respiratory

syndrome coronavirus 2 or Sars-CoV-2. Now declared a pandemic by the World

Health Organization (WHO), most people who contract COVID-19 suffer only mild

symptoms. The WHO says that only one person in six becomes seriously ill

"and will develop difficulty in breathing". Almost all

of the serious consequences of COVID-19 have pneumonia. The WHO also

says that elderly people and people with underlying problems, such as high

blood pressure, heart and lung problems or diabetes, are more likely to develop

serious illnesses [1].

Regularly, when people with COVID-19

develop cough and fever, this is a result of the infection that affects the

bronchial tree. The lining of the bronchi is injured, causing inflammation.

This, in turn, irritates the nerves in the lining of the airways, and in such

situations, just a grain of dust can stimulate coughing. With the evolution of

the condition, the virus reaches the gas exchange units (alveoli), igniting

them and, consequently, promoting the filling of such alveoli by liquids,

cellular debris and others, due to the alterations caused in the

alveolar-capillary membrane. This condition will therefore be characterized as

pneumonia, resulting in an inability of gas exchange with consequent hypoxemia

and hypercapnia. Pneumonic conditions are associated with mortality, especially

in the elderly [1].

Chen et al. [2] retrospectively

studied 99 patients with pneumonia caused by COVID-19. The average age of the

patients was 55.5 years, including 67 men and 32 women. 51% of patients had

chronic diseases. The patients presented clinical manifestations of fever

(83%), cough (82%), shortness of breath (31%), muscle pain (11%), mental

confusion (9%), headache (8%), headache throat (5%), rhinorrhea (4%), chest

pain (2%), diarrhea (2%) and nausea and vomiting (1%). According to the imaging

exam, 75% of patients had bilateral pneumonia, 14% of patients had multiple

spots and ground-glass opacity, and 1% of patients had pneumothorax. 17% of

patients developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and, among them,

11% of patients worsened in a short period and died from multiple organ

failure.

Methods

An integrative literature review was

carried out, with articles published between 2019 and 2020, in the Google and

PubMed databases, using the following search terms: coronavirus, COVID-19,

pulmonary complications, pneumonia, and 06 articles were selected for writing

the present manuscript.

Histopathological

findings

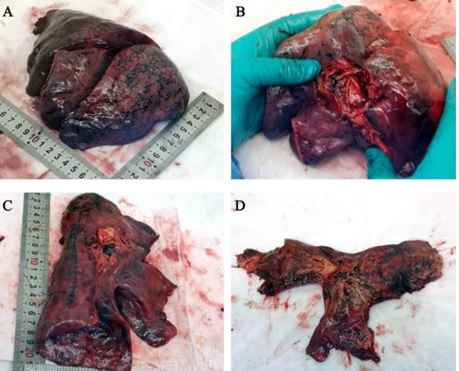

Luo et al. [3] describe, in data

not yet published, histopathological findings related to a 66-year-old male

patient who had symptoms of high fever and cough when he returned to Shenzhen

City, coming from Wuhan on January 4, 2020 This individual had only

hypertension as a comorbidity. On macroscopic examination (Figure 1), the

surface of the entire lung showed a diffuse congestive appearance. There was

punctual hemorrhage and partially hemorrhagic necrosis. Hemorrhagic necrosis

was present mainly on the outer edge of the lower right lobe, middle lobe and

upper lung lobe. The bronchi were swollen and the

mucous surfaces were covered with hemorrhagic exudation. The cut surfaces of

the lung showed severe congestive and hemorrhagic changes.

Figure

1 - Macroscopic lung examination at COVID-19.

Morphology of the right lung (Panel A and B) and the left lung (Panel C and D).

Hemorrhagic necrosis is obvious at the outer edge of the right pulmonary lobe.

Image reproduced from the data of Luo et al. [3].

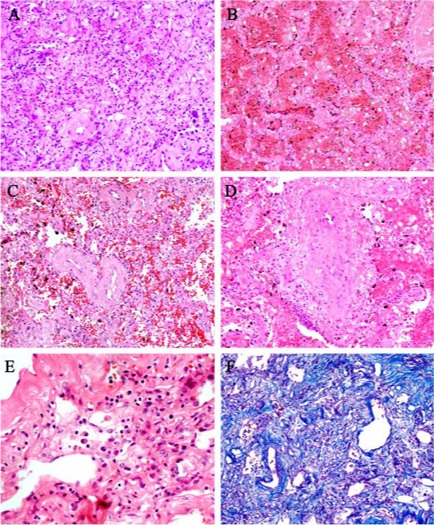

As shown in Figure 2, histopathological

findings showed extensive interstitial fibrosis with partially hyaline

degeneration and pulmonary hemorrhagic infarction. The small vessels showed

hyperplasia, thickening of the vessel wall and stenosis / occlusion.

Interstitial infiltration of inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes and

mononuclear cells. Pulmonary interstitial fibrosis was confirmed, and no other

bacterial and fungal infections were found by special staining.

Figure

2 - Pulmonary interstitial histopathology associated

with a critical patient in COVID-19. A: Massive pulmonary interstitial

fibrosis. B: Pulmonary hemorrhagic infarction. C: Vascular wall thickening and

stenosis of the lumen. D: Thromboangiitis Obliterans

surrounded by inflammatory cells. E: Infiltrated interstitial plasma cells. F:

Pulmonary interstitial fibrosis. Image reproduced from the data of Luo et al.

[3].

There was alveolitis with atrophy,

proliferation, desquamation and various changes in the squamous metaplasia of

alveolar epithelial cells (mainly type ?), as listed

in Figure 3. The remaining pulmonary alveoli showed a thickened septum,

necrosis and desquamation of alveolar epithelial cells. In addition, massive

fibrous exudate, giant multinucleated cells and intracytoplasmic viral

inclusion bodies. Necrotizing bronchiolitis and manifest necrosis of the

bronchiolar wall, with epithelial cells present in the lumen.

Figure

3 - Changes in the pulmonary alveoli of COVID-19. A:

Necrotizing bronchiolitis, necrotic bronchial epithelial cells are present in

the lumen. B: Atrophy of alveolar epithelial cells. C and D: Various changes in

squamous metaplasia of alveolar cells. E: Thickened alveolar septum. F:

Necrosis and desquamation of alveolar epithelial cells. G: massive fibrinous

exudate in the lumen. H: Multinucleated giant cell. I: Intracytoplasmic viral

inclusion body in an alveolar epithelial cell (indicated in the box). Image

reproduced from the data of Luo et al. [3].

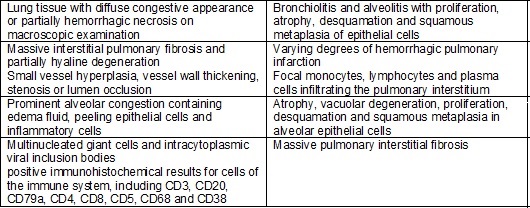

Chart

I - Summary of anatomical and pulmonary

histopathological findings in COVID-19, based on the study by Luo et al. [3].

Abnormalities

seen on chest tomography (CT)

COVID-19 pneumonia manifests with

abnormalities in chest CT, even in asymptomatic patients, with rapid evolution

of unilateral to diffuse bilateral ground-glass opacities that evolve or

coexist with consolidations in 1-3 weeks. Combining the assessment of imaging

resources with clinical and laboratory findings can facilitate the early

diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia [4].

Abnormalities

in chest CT before symptoms

Shi et al. [4] retrospectively

reviewed the chest CT findings of 81 patients with confirmed COVID-19. Patients

were subdivided into 4 groups based on the duration of clinical symptoms. Group

1 consisted of 15 patients who underwent a chest CT scan before any clinical

symptoms; group 2 underwent a CT scan within 7 days after the onset of

symptoms; group 3 patients were examined 7 to 14 days after the onset of

symptoms. It is important to note that all 81 patients [including those without

symptoms] had an abnormal chest CT consistent with viral pneumonia. In the

asymptomatic group, the typical pattern was ground-glass, multifocal and

peripheral opacities (figure 4). Thickening of the interlobular septum,

thickening of the adjacent pleura, nodules, round cystic changes,

bronchiectasis, pleural effusion and lymphadenopathy were rarely observed in

the asymptomatic group.

Figure

4 - Illustration of the evolution of chest CT during

COVID-19. Hypothetical initial stage with bilateral, multifocal and predominantly

peripheral ground-glass opacity. Source: author's archive image.

Still analyzing the study by Shi et al.

[4], there was radiographic progression after the first symptoms. In group 2

(that is, in the first 7 days of symptoms), CT chest lesions became bilateral

in 90% and diffuse in more than 50%, predominantly with ground-glass opacities

(figure 05). Pleural effusion and some cases of lymphadenopathy were also

detected in group 2. In group 3 (ie, 7 to 14 days

after symptoms), the ground-glass aspect was still the predominant finding on

CT in more than 50% of cases, however, consolidation patterns were also seen in

about a third of patients. Finally, in group 4 (that is, more than 14 days

after symptoms), ground-glass opacities and reticular patterns were more

common.

Figure

5 - Illustration of the further evolution of

ground-based opacities in ground glass in COVID-19. The lesions are now

bilateral and multifocal. Source: author's archive image.

Association

of COVID-19 with hemoglobin

Wenzhong & Hualan [5] released the results of their study, mentioning

that in the viral replication phase after entering a person's organism,

coronavirus RNA encodes the production of structural proteins (for the

structure of the virus) and other non-structural proteins. One of these

non-structural proteins invades hemoglobins, removes

the iron atom and binds at the site, preventing oxygen from being carried. This

would explain the rapidly evolving hypoxia picture. They postulate that the

lung parenchyma lesions (ground glass) are a consequence of hypoxia and

consequent necrosis and not a direct effect of the inflammatory process caused

by the virus. This could explain people with comorbidities, especially

diabetes, who decompensate quickly due to hypoxia, sometimes even with

supplemental oxygen supply, as these individuals would have fewer binding sites

in hemoglobins. Theoretically, in people without

comorbidities, the initial viral load would be responsible for determining the

severity of the condition since the higher the viral load, the more

theoretically there are compromised hemoglobins. It

is also suggested that the change in the structure of red blood cells would

explain vessel damage and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Conclusion

Infection of the individual by

COVID-19 has the potential to cause significant changes in ventilatory

capacity, leading to diffuse pulmonary impairment and worsening gas exchange.

Further studies are needed to clarify the pathophysiology of this complex

disease with high potential for spread, morbidity and mortality.

References

- World

Health Organization - WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic [accessed in

Apr 10 2020]; Available in:

https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- Chen

N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang

J, Liu Y, Wei Y, Xia J, Yu T, Zhang X, Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical

characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan,

China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507-13.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7

- Luo

W, Yu H, Gou J, Li X, Sun Y, Li J, Liu L. Clinical Pathology of Critical

Patient with Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (COVID-19). Preprints 2020, 2020020407

[periódicos na Internet]. [acesso em 10 abr 2020];

Disponível em: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202002.0407/v1

- Shi

H, Han X, Jiang N, Cao Y, Alwalid O, Gu J, Fan Y,

Zheng C. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in

Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20(4):425-34.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4

- Wenzhong L, Hualan

L. COVID-19: Attacks the 1-Beta Chain of Hemoglobin and Captures the Porphyrin

to Inhibit Human Heme Metabolism. ChemRxiv 2020; Preprint. https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv.11938173.v6