Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc 2021;20(1):93-100

doi: 10.33233/rbfex.v20i1.4090

REVIEW

Physical exercise during the COVID-19 pandemic for

individuals with a risk factor for cardiovascular disease: benefits and safety

Exercício

físico durante a pandemia da COVID-19 para indivíduos com fator de risco para

doença cardiovascular: benefícios e segurança

Wallace

Machado Magalhães de Souza1,2,3, Diogo Van Bavel

Bezerra1,4, Michel Silva Reis1,2,4

1Grupo de Pesquisa em Avaliação e

Reabilitação Cardiorrespiratória (GECARE), Universidade Federal do Rio de

Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil

2Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro,

Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil

3Centro de Cardiologia do Exercício,

Instituto Estadual de Cardiologia Aloysio de Castro (CCEx/IECAC),

Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil

4Instituto do Coração Edson Saad,

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (ICES/UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil

Received on: May 3, 2020; accepted on:

September 8, 2020.

Correspondence: Wallace Machado Magalhães de Souza, Grupo de Pesquisa em

Avaliação e Reabilitação Cardiorrespiratória, Universidade Federal do Rio de

Janeiro, Rua Prof. Rodolpho Paulo Rocco, 255, 21941-590 Rio de Janeiro RJ

Wallace Machado Magalhães de Souza: wallacemachado@ufrj.br

Diogo Van Bavel Bezerra:

diogobavel@gmail.com

Michel Silva Reis: msreis@hucff.ufrj.br

Abstract

Introduction: Physical

exercise is one of the main components of the cardiovascular rehabilitation

program (CR). However, due to the social isolation adopted by public

authorities because of the new coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), the performance

of CR in an outpatient setting is impractical at this time. Objective:

To discuss about safe, efficient, and pleasant physical exercise strategies for

individuals with clinically stable risk factors for cardiovascular disease,

outside the traditional CR environment. Methods: Narrative literature

review with search of the sources made in Medline databases via PubMed and

Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciElo),

without date limit, with the key-words: physical exercise, coronavirus,

cardiovascular rehabilitation and risk factors for cardiovascular disease, in

Portuguese and English. Results: 25 articles and 1 book in electronic

format were included. Conclusion: The physical exercise program improves

functional capacity, muscle strength, oxygen perfusion, mental and social status and quality of life, minimizing the negative impact

of social isolation on health. Thus, the recommendations suggested in this

article are safe measures that bring benefits to individuals with risk factors

for CVD.

Keywords: cardiovascular rehabilitation;

functional capacity; coronavírus.

Resumo

Introdução: O exercício físico é um dos principais

pilares do programa de reabilitação cardiovascular (RC). Entretanto, devido ao

isolamento social adotado pelas autoridades públicas por causa da pandemia da

infecção provocada pelo novo coronavírus (COVID-19),

a realização de RC em ambiente ambulatorial é impraticável neste momento. Objetivo:

Discutir sobre estratégias seguras, eficientes e prazerosas de exercícios

físicos para indivíduos com fatores de risco para doença cardiovascular (DCV),

clinicamente estáveis, fora do ambiente tradicional de RC. Métodos:

Revisão de literatura narrativa com busca das fontes realizadas nas bases de

dados Medline via PubMed e Scientific

Electronic Library Online (SciElo),

sem limite de data, com as palavras-chave: exercício físico, coronavírus, reabilitação cardiovascular e fatores de risco

para doença cardiovascular, em português e inglês. Resultados: Foram

incluídos 25 artigos e 1 livro no formato eletrônico. Conclusão: O

programa de exercício físico provoca melhoras na capacidade funcional, força

muscular, perfusão de oxigênio, estado mental e social e a qualidade de vida,

minimizando o impacto negativo do isolamento social na saúde. Desta forma, as

recomendações sugeridas neste artigo são medidas seguras e que trazem

benefícios para indivíduos com fatores de risco para DCV.

Palavras-chave: reabilitação cardiovascular;

capacidade funcional; coronavírus.

Introduction

Patients with

risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) (i.e., obesity, systemic arterial

hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia) are eligible for

cardiovascular rehabilitation (CR) programs. Outpatient CR involves several

components to improve the physical, mental, and social health of the

participants and must occur under the supervision of a multi-professional team composed

of doctors, physiotherapists, Physical Education teachers, nutritionists,

psychologists, social workers, and nurses. In this environment, educational

activities are carried out on health care in several aspects. Among the

activities developed in outpatient CR, physical exercise is one of the main

pillars due to its well-pronounced benefits in functional capacity, in the

control of risk factors, and the quality of life in this population [1].

However, the

social isolation measures certainly adopted by the World Health Organization

(WHO) and public authorities due to the pandemic of the new coronavirus

infection (COVID-19), caused by SARS-CoV-2, prevent the practice of physical

exercises in CR is carried out by security measures of this population. Data

presented by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention point to a

lethality rate of 2.3% by COVID-19 (1,023 deaths out of 44,672 confirmed

cases). Still, when patients had some risk factors for CVD, such as systemic

arterial hypertension or diabetes mellitus, this rate reached 10.5%, which

shows that this population is more vulnerable when infected by the virus [2].

This social seclusion can induce sedentary behaviors, favoring an increase in

body mass, an increase in systemic blood pressure, greater intolerance to

glucose, dyslipidemia, as well as psychosocial disorders such as depression and

anxiety [3]. The psychological impact of prolonged quarantine is associated

with feelings of anger, frustration, boredom, controversial information (i.e.,

fake news), and financial losses [4].

Therefore, due

to this challenging scenario that will last for a long period, the objective of

this article is to discuss the safety of prescription, efficiency and

enjoyment of physical exercises for requirements with risk factors for

clinically stable CVD (i.e., with optimized medication and no signs/symptoms of

uncontrolled blood pressure and/or blood glucose) for the traditional CR

environment.

Methods

A

narrative literature review was carried out with the search for sources made on

Medline via PubMed and Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciElo), with no date limit, with the key-words: physical

exercise, coronavirus, cardiovascular rehabilitation and risk factors for

cardiovascular disease, in Portuguese and English.

Benefits of physical exercise

If, on the one

hand, social isolation is crucial for patients with risk factors for CVD,

avoiding greater exposure to the virus, on the other hand, this withdrawal can

lead to a reduction in daily physical activities and physical exercise

practices [5]. Physical exercise is a way to improve the health of this

population, with significant effects on glucose metabolism, on skeletal muscle

function, on the respiratory, cardiac, and bone systems [6], on improving

mental health [7], on endothelial function, reduced levels of lipoproteins and

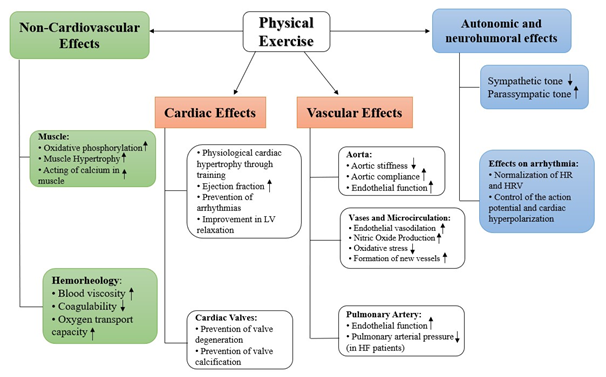

atherosclerotic lesions [8] and other organs (Figure 1).

Prolonged

periods of physical inactivity lead to changes in the sympathovagal

modulation and oxidative function of skeletal muscle, resulting in reduced

stroke volume and peripheral muscle dysfunction [9]. WHO data from 2016

indicate that 44% of the causes of death worldwide were cardiovascular

etiology. When physical inactivity is associated with some heart disease, the

risk of mortality increases significantly [10].

HR =

Heart rate; HRV = Heart rate variability; HF = Heart failure; LV = Left

ventricle. Niebauer J, 1996 [11]; Gielen

et al., 2010 [12].

Figure 1 - Effect of physical exercise

on the myocardium, blood vessels, and skeletal muscle

In patients with

risk factors for CVD, there is a significant improvement in functional

capacity, blood pressure, and quality of life with interventions through

aerobic and/or strength exercise, with no risk associated with disease

progression [13,14]. A study carried out with 5,641 patients with coronary

artery disease submitted to a CR program concluded that an increase of 1 MET

(metabolic equivalent) was able to reduce the risk of cardiovascular mortality

by 25% [15]. A recent meta-analysis pointed out that aerobic training combined

with strength training improved oxygen consumption at peak effort (VO2peak),

muscle strength, and quality of life in patients with heart failure, mainly due

to improved transport capacity and use of oxygen by peripheral musculature

[16].

Physical

exercise at home environment is considered an essential tool for the prevention

and treatment of diseases related to physical inactivity, especially in

situations where practice outside this environment is not possible [17]. In

this sense, even minimal amounts of physical exercise at home environment

(e.g., walking for 20 minutes) promote reductions in the risk of mortality from

CVD by improving systemic blood pressure and glycemic control [18].

Thus, physical

exercise promotes physiological adaptations that increase the perfusion and

oxygen supply to the cardiac and skeletal muscle, resulting in improvement of

peripheral muscle dysfunction, as a consequence, contributing to the reduction

of effort intolerance and risk of cardiovascular mortality in individuals with

factors risk factors for CVD [19].

Recommendations for physical exercise prescription

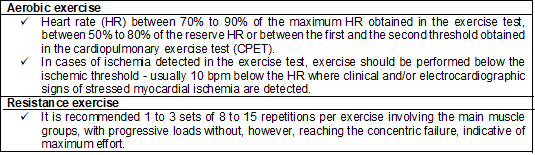

The current

Brazilian Cardiovascular Rehabilitation Guideline provides the following

recommendations for patients with clinically stable CVD risk factors for

physical exercise and will be presented in Chart 1 [1]:

Chart 1 - Recommendations for exercises

to improve functional capacity in cardiac patients

HR =

Heart rate. CPET = Cardiopulmonary exercise test. Carvalho et al., 2020 [1]

Although the

recommendations for exercise intensity are based on physiological parameters

(i.e., HR), the use of these indices can be difficult to monitor by the

patients themselves due to 1) lack of technological resources to monitor HR

(e.g., heart rate monitor); 2) lack of knowledge on how to measure HR using the

radial pulse and; 3) the influence of the fitness level on the HR response,

through sympathovagal modulation, in which the same

absolute HR value can represent a different physiological response, according

to the individual's fitness level.

As an

alternative that is easily accessible and understood by most people, especially

when performing physical exercises without direct supervision by a

multi-professional team, the intensity of the effort can be controlled by a

subjective effort perception scale. Among these scales, the most known and used

is the Borg Scale [20], which was originally developed on a scale of 6 to 20

and, alternatively, has a version adapted on a scale of 0 to 10 (Picture 2).

Borg,

1990 [20]

Figure 2 - Borg Scale (scale from 0 to

10)

The use of the

Borg Scale is a strategy widely used in exercise tests and the prescription of

physical exercise, both for cardiac patients and healthy individuals [21,22].

The safe training intensity should represent an effort up to 4 (on a scale from

0 to 10), corresponding to the intensity considered moderate. Thus, as a way of

controlling the intensity of effort, the Borg Scale is an important control

tool for self-monitoring during physical exercises [23].

Thus, the

physical exercise program for patients with risk factors for CVD to perform at

home should consider the following points:

- Training frequency: Three to five times a week,

respecting the rest interval so that there are no harmful effects on the body

due to overtraining.

- Session duration: Initially, 20 minutes a day,

progressing gradually until reaching 60 minutes a day.

- Intensity: HR or Borg Scale, as previously discussed.

- Modality: Due to limited resources and space, it is

recommended that circuit exercises with their body weight and using home

equipment (i.e., chair, broom, bottles).

- Safety: It must be ensured that the place does not

have objects that can facilitate the fall or cause trauma during the execution

of physical exercises (i.e., carpets, furniture, toys). Also, whenever

possible, monitor the levels of blood pressure (hypertension) and capillary

blood glucose (diabetics) before and after exercise.

The training

sessions must consist of: 1) the warm-up phase, to

prepare the body for the increase in physiological demand; 2) training itself

and; 3) cool down, to help to return physiological parameters to rest indexes.

Physical

exercises should be stopped immediately if angina, severe dyspnoea,

syncope, and headache are present. However, in the presence of fever, the

practice of physical exercise is contraindicated, at least on that day.

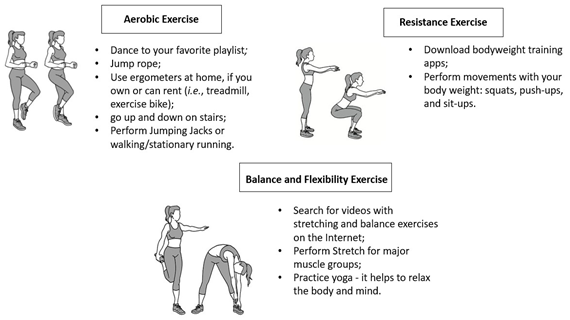

Suggested physical exercises to be performed at home

There is a

challenge in prescribing physical exercises in the home environment due to the

limitation of equipment/resources for the execution of different types of

movements and the difficulty in controlling the variables and performing the

exercises. Besides, the physical exercise program should promote pleasant

experiences for the individual in a way that facilitates their adherence to a

daily training routine [24]. With that in mind, the American College of

Exercise Medicine (ACSM) and the Brazilian Society of Cardiology (SBC) prepare

documents that endorse the importance of staying active during this period and

suggestions for exercises that can be performed safely, pleasantly, and

efficiently indoors (Figure 3) [23,25]:

Reis

et al., 2020 [23]; American College of Sports Medicine, 2020 [25]

Figure 3 - Suggested physical exercises

to be performed at home

Bearing in mind

that social support is an essential factor for adhering to the physical

exercise program, establishing a positive relationship to encourage this

practice among family members is crucial for regular training and especially

maintenance in this training program [26]. In this way, exercises that involve

the spouse, children, and other family members can increase the positive

aspects of the training experience and promote greater adherence during the

period of pandemic and social isolation [24].

Conclusion

In this context,

it is extremely important for patients with risk factors for CVD to remain

physically active during the period of social isolation since sedentary

behavior causes damage in the clinical and functional framework. The physical

exercise program improves functional capacity, muscle strength, oxygen

perfusion, mental and social status, and quality of life. Following the

guidelines presented in this article can minimize the negative impact of social

isolation on health. Thus, the recommendations suggested in this article are

safety measures that bring benefits to individuals with risk factors for CVD.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of

interest.

Financing source

There were no sources of external funding for this

study.

Authors' contributions

Conception and design of the research:

Souza WMM, Bezerra DVB. Data collection: Souza

WMM, Bezerra DVB. Analysis and interpretation of

data: Souza WMM, Bezerra DVB. Writing of the

paper: Souza WMM, Bezerra DVB, Reis MS. Critical

review of the paper for important intellectual content: Reis MS.

References

- Carvalho

T, Milani M, Ferraz AS, Silveira AD, Herdy AH, Hossri CAC et al. Diretriz Brasileira de Reabilitação

Cardiovascular – 2020. Arq Bras

Cardiol 2020;114(5):849-93. doi: 10.36660/abc.20200407 [Crossref]

- Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020;5(7):811-18. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017 [Crossref]

- Ferreira MJ, Irigoyen MC, Consolim-Colombo F, Saraiva JFK, Angelis K. Physically Active Lifestyle as an Approach to Confronting COVID-19. Arq Bras Cardiol 2020;114(4):601-2. doi: 10.36660/abc.20200235 [Crossref]

- Jiménez-Pavón D, Carbonell-Baeza A, Lavie CJ. Physical exercise as therapy to fight against the mental and physical consequences of COVID-19 quarantine: Special focus in older people. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.03.009 [Crossref]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020;395(2):912-20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [Crossref]

- Fiuza-Luces C, Garatachea N, Berger NA, Lucia A. Exercise is the real polypill. Physiology (Bethesda) 2013;28(5):330-58. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00019.2013 [Crossref]

- Mikkelsen K, Stojanovska L, Polenakovic M, Bosevski M, Apostolopoulos V. Exercise and mental health. Maturitas 2017;106(9):48-56. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.09.003 [Crossref]

- Santos LF, Vicente GA, Correa LMA. Reabilitação cardiovascular com ênfase no exercício físico para pacientes com doença arterial coronariana: visão crítica do cenário atual. Revista da Sociedade de Cardiologia do Estado de São Paulo 2019;29(3):303-13. doi: 10.29381/0103-8559/20192903306-13 [Crossref]

- Perhonen

MA, Franco F, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Blomqvist

CG, Zerwekh JE et al. Cardiac atrophy

after bed rest and spaceflight. J Appl Physiol (1985)

2001;91(2):645-53. https://doi:10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.645 [Crossref]

- Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;139(10):e56-e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [Crossref]

- Niebauer J, Cooke JP. Cardiovascular effects of exercise: role of endothelial shear stress. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28(7):1652-60. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(96)00393-2 [Crossref]

- Gielen S, Schuler G, Adams V. Cardiovascular effects of exercise training: molecular mechanisms. Circulation 2010;122(12):1221-38. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.939959 [Crossref]

- Bocchi EA. Exercise training in Chagas' cardiomyopathy: trials are welcome for this neglected heart disease. European Journal of Heart Failure 2010;12(8):782-4. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq124 [Crossref]

- Laoutaris ID, Adamopoulos S, Manginas A, Panagiotakos DB, Kallistratos MS, Doulaptsis C et al. Benefits of combined aerobic/resistance/inspiratory training in patients with chronic heart failure. A complete exercise model? A prospective randomised study. Int J Cardiol 2013;167(5):1967-72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.05.019 [Crossref]

- Martin BJ, Arena R, Haykowsky M, Hauer T, Austford LD, Knudtson M et al. Cardiovascular fitness and mortality after contemporary cardiac rehabilitation. Mayo Clin Proc 2013;88(5):455-63. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.02.013 [Crossref]

- Gomes-Neto M, Durães AR, Conceição LSR, Roever L, Silva CM, Alves IGN et al. Effect of combined aerobic and resistance training on peak oxygen consumption, muscle strength and health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2019;293(6):165-75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.02.050 [Crossref]

- Schwendinger F, Pocecco E. Counteracting physical inactivity during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence-based recommendations for home-based exercise. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(6):2-6. https://doi:10.3390/ijerph17113909 [Crossref]

- Castro RRT, Neto JGS, Castro RRT. Exercise training: a

hero that can fight two pandemics at once. International Journal of

Cardiovascular Sciences 2020;33(3):284-7. doi: 10.36660/ijcs.20200083 [Crossref]

- Drexler H, Riede U, Münzel T, König H, Funke E, Just H. Alterations of skeletal muscle in chronic heart failure. Circulation 1992;85(5):1751-9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.85.5.1751 [Crossref]

- Borg G. Psychophysical scaling with applications in physical work and the perception of exertion. Scand J Work Environ Health 1990;16 Suppl 1:55-8. https://doi:10.5271/sjweh.1815 [Crossref]

- Kaercher PLK, Glänzel MH, Rocha GG, Schmidt LM, Nepomuceno P, Stroschöen L et al. Escala de percepção subjetiva de esforço de Borg como ferramenta de monitorização da intensidade de esforço físico. Revista Brasileira de Prescrição e Fisiologia do Exercício 2018;12:1180-5.

- Meneghelo RS, Morhy SS, Zucchi P. Time of exercise as indicator of quality control in ergometry services. Arq Bras Cardiol 2014;102(2):151-5. doi: 10.5935/abc.20140005 [Crossref]

- Reis

MS, Oliveira GMM, Guio BM, Bezerra DVB, Pinto EP, Nasser I et al. Como cuidar

do seu coração na pandemia da COVID-19: Recomendações para a prática

de exercícios físicos e respiratórios. Rio

de Janeiro. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ),

Departamento de Fisioterapia, Programa de

Pós-Graduação em Educação

Física e Cardiologia,

Grupo de Pesquisa em Avaliação e

Reabilitação Cardiorrespiratória (GECARE); 2020. p.1-21. [Cited 2021 dez 10]. Available from: http://poscardio.ufrj.br/images/documentos/EBook_COVID19_respirat%C3%B3ria.pdf

- Oliveira

Neto L, Elsangedy HM, Tavares VDO, Teixeira CVLS, Behm DG, Da Silva-Grigoletto ME. #TrainingInHome

- Home-based training during COVID-19 (SARS-COV2) pandemic: physical exercise

and behavior-based approach. Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc 2020;19(2):S9-S15. doi: 10.33233/rbfe.v19i2.4006 [Crossref]

- American College of Sports Medicine. Staying active

during the coronavirus pandemic exercise is medicine, 2020. [cited 2020 abr

15]. Available from: https://www.exerciseismedicine.org/assets/page_documents/EIM_Rx%20for%20Health_%20Staying%20Active%20During%20Coronavirus%20Pandemic.pdf

- Pridgeon L, Grogan S. Understanding exercise adherence and dropout: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of men and women’s accounts of gym attendance and non-attendance. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 2012;4(8):382-99. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2012.712984 [Crossref]