Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc 2021;20(1):101-24

doi: 10.33233/rbfex.v20i1.4254

REVIEW

Recommendations for physical activity during COVID-19:

an integrative review

Recomendações

para a prática de exercício físico em face do COVID-19: uma revisão integrativa

Carlos

José Nogueira1,2, Antônio Carlos Leal Cortez1,3,5,

Silvânia Matheus de Oliveira Leal1,6, Estélio

Henrique Martin Dantas1,4,5

1Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de

Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

2Escola Preparatória de Cadetes do Ar -

EPCAR / Força Aérea Brasileira (FAB), Barbacena, MG, Brazil

3Centro Universitário Santo Agostinho,

Teresina, PI, Brazil

4Universidade Tiradentes, Aracajú, SE, Brazil

5Academia Paralímpica Brasileira, São

Paulo, SP, Brazil

6Instituto Brasiliense de Fisioterapia,

Brasília, DF, Brazil

Received on: June 6, 2020;

Accepted on: October 12, 2020.

Correspondence: Carlos José Nogueira, Universidade Federal do Estado do

Rio de Janeiro - UNIRIO / Laboratório de Biociências da Motricidade Humana

(LABIMH), Rua Dr Xavier Sigaud,

290/301, 22290-180 Rio de Janeiro RJ

Carlos José Nogueira: carlosjn29@yahoo.com.br

Antônio Carlos Leal Cortez:

antoniocarloscortez@hotmail.com

Silvânia Matheus de Oliveira Leal:

silvaniamatheus123@hotmail.com

Estélio Henrique Martin Dantas:

estelio@pesquisador.cnpq.br

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate and synthesize the

scientific evidence in relation to the recommendations on the practice of

physical activity during and after the pandemic period. Methods: A

search was carried out with the Medline/Pubmed,

Cochrane, Web of Science and Scopus databases, and manual searches in journals,

in the references of the selected studies, in addition to the use of pre-print

studies. The initial search totaled 1026 records and after applying the

filters, 321 publications were selected. After the exclusion by title, summary,

duplicates, and full reading, 13 publications remained, in addition to another

10 studies selected manually, totaling 23 publications. Results: After

analyzing the results, the evidence was categorized according to: the effects

of physical exercise on viral respiratory infections, the impact of COVID-19 in

relation to physical inactivity, physical and mental health and recommendations

on regular physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic and recommendations

on post-pandemic physical activity. Conclusion: Most evidence recommends

regular moderate physical activity during and after the pandemic. However, more

specific recommendations on intensity, type of exercise, sets and duration of

training need further investigation.

Keywords: exercise; coronavirus; coronavirus infections; exercise therapy.

Resumo

Objetivo:

Avaliar e sintetizar as evidências

científicas com relação as

recomendações sobre a prática de atividade

física durante

e após o período da pandemia. Métodos: Realizou-se uma busca junto às

bases Medline/Pubmed, Cochrane, Web of Science e Scopus, e buscas manuais em periódicos, nas

referências dos estudos selecionados, além da utilização de estudos pré-print. A busca inicial totalizou 1026 registros e após

a aplicação dos filtros, 321 publicações foram selecionadas. Após a exclusão

por título, resumo, duplicatas e leitura na íntegra restaram 13 publicações,

além de mais 10 estudos selecionados manualmente, totalizando 23 publicações. Resultados:

Após análise dos resultados, as evidências foram

categorizadas de acordo com:

os efeitos do exercício físico sobre

infecções respiratórias virais, o impacto

da COVID-19 em relação à inatividade

física, saúde física e mental e

recomendações

sobre a atividade física regular durante a pandemia da COVID-19

e recomendações

sobre atividade física pós pandemia. Conclusão: A maioria das evidências

recomendam a realização de atividade física moderada regular durante e após a

pandemia. No entanto, recomendações mais específicas sobre a intensidade, o

tipo de exercício, séries e duração do treino precisam de maiores

investigações.

Palavras-chave: exercício físico; coronavírus;

infecções por coronavírus; terapia por exercício.

Introduction

Coronavirus

(COVID-19) emerged in late December 2019, in the city of Wuhan in China, as the

leading cause of viral pneumonia [1,2,3] and spread rapidly across the country

and all continents in the world [2,4,5,6]. In March 2020, the World Health

Organization (WHO) declared the SARS-Cov-2 virus to be a global pandemic [3,7].

The current

COVID-19 pandemic presents an unexpected public health challenge. Ambitious

measures are being implemented worldwide by governments, non-governmental organizations,

and individuals to delay the spread of the virus and prevent overloading the

health system [8]. However, much remains to be done to "flatten the

curve" and mitigate the impact of the coronavirus [9].

The transmission

of SARS-Cov-2 occurs mainly from the respiratory spread from person to person

(people in close contact or through respiratory droplets produced when an

infected person coughs or sneezes) and, to a lesser extent, from contact with

infected people, surfaces or objects [1,10]

Clinical

conditions such as hypertension, respiratory, cardiovascular, and metabolic

diseases are important risk factors for severity in COVID-19 [11,12]. Current

studies point to potential risk groups: the elderly [11,13,14], young adults,

obese individuals with the comorbidities described above, chronic diseases with

hemodynamic and immunological repercussions [6,15].

According to Carda et al. [16], COVID-19 has different clinical

manifestations and the most observed are: 1) mild: no dyspnea, no low blood

oxygen saturation (SatO2), with or without fever spikes, loss of

smell and taste; 2) moderate: dyspnea during light or strenuous activities,

SatO2 94% to 98%, and radiological signs of pneumonia; 3) severe:

dyspnea, SatO2 ≤ 93%, respiratory rate (RR) > 30/min,

radiological progression of the lesions, need for O2

supplementation, possibly with non-invasive ventilation; and 4) critical:

patients need mechanical ventilation.

Physical

activity helps to improve immunity in the prevention and complementary

treatment for chronic diseases and viral infections such as the new coronavirus

[1,6,11,17,18,19,20,21,22]. The protective effect of exercise on the immune system is

crucial to adequately respond to the threat of COVID-19 [15,21,23].

Regular physical

activities of moderate to vigorous intensity, according to the guidelines of

the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), will improve the immune

responses to infections; decrease chronic low-grade inflammation, and improve

immunological and inflammatory markers in various disease states, including

cancer, HIV, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cognitive impairment, and

obesity [21,23].

To fight

sedentary lifestyle and improve physical and mental health, ACSM [24] recently

released a guide suggesting that moderate-intensity physical activity (PA)

should be maintained in the COVID-19 quarantine, emphasizing the importance of

every physically active minute for health. The guidelines, in the current

situation, suggest 150 to 300 minutes per week of aerobic physical activity of

moderate intensity and two sessions per week of muscle strength training

[11,24].

This

recommendation is also for people in social distance who are not infected with

COVID-19 and people who are infected but remain asymptomatic. If symptoms

persist, exercise should be stopped, and the individual should seek medical

advice [25].

Although

containing the virus as quickly as possible is an urgent public health

priority, there are few guidelines for the public on what people can or should

do in terms of maintaining their daily exercise or physical activity routines

[26].

Given the

concerns about the increasing spread of COVID-19, it is imperative that

infection control and safety precautions, as well as appropriate recommendations

for physical exercise, be followed [26].

In view of the

world pandemic of COVID-19 and the inevitable need of the population to remain

active mainly through physical activity, the present study aims to evaluate and

summarize the scientific evidence on the recommendations for engaging in

physical activity and exercise during and after the pandemic COVID-19.

Methods

The stages of

this review were conducted based on methodology that provides synthesis of

knowledge and applicability of results of significant publications to practice

[27].

The review

followed the following stages: formulation of the guiding question; selection

of studies based on the year of publication and title; selection of studies by

their abstracts and selection by the full text; and afterwards, extraction of

data from the studies included; evaluation and interpretation of results, and,

finally, presentation of the review of the knowledge produced [28].

Selection of studies

The literature

survey was carried out in the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System

Online (MEDLINE) databases through the National Library of Medicine (PUBMED),

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Web of Science, and Scopus.

Other sources were also searched: journal hand-searching, references described

in the selected studies, and use of unpublished material (pre-print).

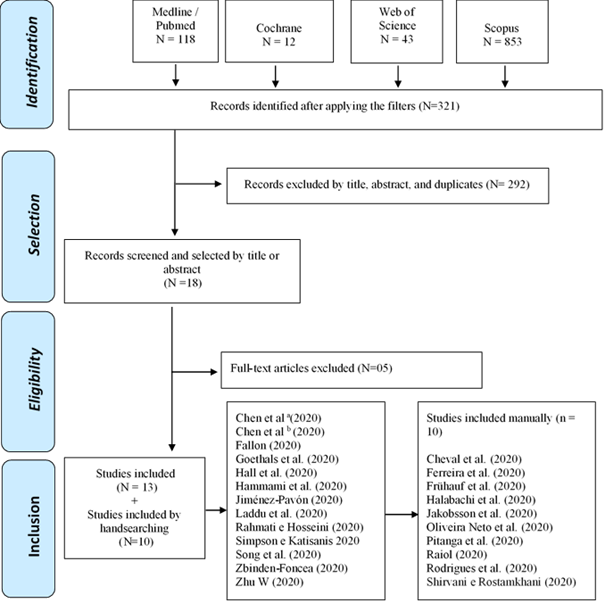

The initial

search identified 1026 records and after applying the filters, 321 publications

were selected. After removing duplicates, manual screening was performed and

those that were not relevant were excluded. Selected publications were assessed

in full text for eligibility. Those that did not meet the inclusion criteria

were excluded. Ten (10) publications were included by journal handsearching and

references in the selected and pre-print studies. The selection of publications

is described in the flowchart (Figure 1).

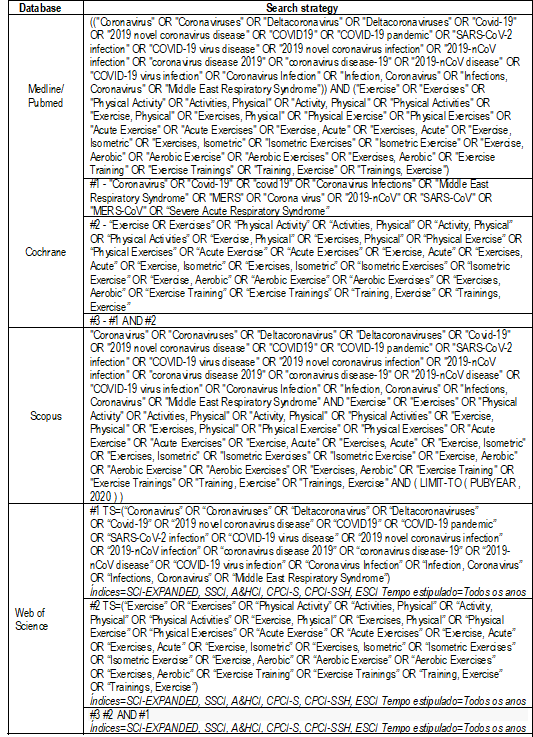

Search strategy

The search was

carried out by trained researchers with experience in the topic of the

articles. The searches were carried out in April 2020. The descriptors selected

in the Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) and Medical

Subjetc Headings (MeSH) were: exercise, coronavirus, covid-19, and coronavirus

infections, as described and presented together with the search strategy in

Chart 1. From this search, publications for complete reading that met the

inclusion criteria for this review were selected. Regarding the scientific

analysis of publications, according to Qualis CAPES

and SCImago Journal Rank (SJR), it was observed that

52.2% were classified as belonging to extract A by Qualis

CAPES and 34% of publications were classified as belonging to quartile 1 (Q1)

according to SJR.

Source:

Author 2020

Chart I - Controlled descriptors used

to build the search strategy in the Medline/Pubmed,

Cochrane, Web of Science, and Scopus databases

Eligibility criteria

Full articles in

English, Spanish, or Portuguese related to the effects of exercise and

recommendations on PA during and after the COVID-19 pandemic were included. The

evidence included original articles and consensus, reviews, editorials,

interviews, in addition to studies in the pre-publication phase (pre-print).

Data extraction

The summary

included the extraction of the following data: authors and year of publication,

type of study, objective, and evidence. Finally, the results relevant to

current knowledge on the study topic were evaluated for producing evidence.

Results

The search

identified 1026 records and after applying the filters, 321 publications were

selected. Two-hundred ninety-seven (297) studies were excluded by title,

abstract, duplicates, and after reading full-text articles. At the end, 13 publications

made up the sample and were analyzed, in addition to another 10

pre-print studies hand selected. Figure 1 (Prisma Flow) describes the

path taken to select the studies, according to the consulted basis.

According to the

descriptors used in the research, 118 publications were identified in Medline/Pubmed, 12 in Cochrane, 43 in Web of Science and 853 in

Scopus. Figure 1 shows the search strategy after applying the filters in the

Prisma Flow diagram.

Source:

Author, 2020 adaptation by Moher et al. (2008) [29]

Figure 1 - Flow diagram of article

selection (Prisma Flow)

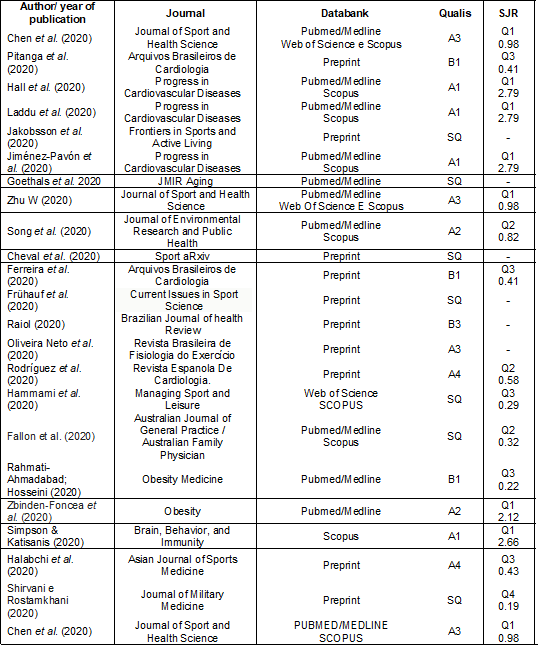

A narrative

synthesis of the selected publications was carried out, presenting the

scientific evidence on physical exercise and COVID-19 and the main

recommendations for physical activity during and after the pandemic. Data

extraction was performed with a specific instrument, containing information

about authors; year of publication; journal, database, Qualis,

SJR, as well as the identification of the scientific evidence of the selected

studies. The included reports were organized in tables according to the

identified variables.

**Preprint = study hand selected (Preprint means pre-publication: a scientific study that has not yet been published). SQ: Without QUALIS; Source: Author, 2020

Chart II - Synthesis of the reports

included in the integrative review, according to author/year of publication,

journal, database, Qualis and SJR

Table II shows

that the journals that published articles on the topic are dispersed. Two

journals (Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases and Journal of Sport and Health

Science) published 03 articles each, making 26.6% of the total articles

selected. Of these journals, 47.83% are indexed in Pubmed/Medline

and 43% in Scopus and, it is noteworthy that some journals are indexed in more

than one database.

Taking into

account Qualis Capes (Brazilian journal evaluation

system) and SJR (a measure of the scientific influence of academic journals

that accounts for the number of citations received by a journal and the

importance or prestige of the cited journals), we found that 52.2% were

classified as Qualis A and, 8 journals, 34.8%, were

classified and qualified as Q1 by SJR.

After analyzing

the results, four thematic categories emerged, which were characterized below

and presented according to their scientific evidence on physical activity and

COVID-19 in Table III:

a) Effects of physical exercise on viral respiratory infections;

b) Impact of COVID-19 related to physical inactivity,

physical and mental health;

c) Recommendations on regular physical activity during

the COVID-19 pandemic;

d) Recommendations on post-COVID-19 physical activity.

Chart III - Systematization of the main

evidence on physical activity related to COVID-19 (see PDF annexed)

Discussion

Effects of physical activity on viral respiratory

infections

The main

question in sports and exercise medicine is whether physical activity is

appropriate during the viral respiratory tract epidemic or not [1]. Studies

have indicated that exercise performed at moderate intensity has positive

effects on the immune system's responses to viral respiratory infections

[17,19,23,30,41,42,43] and is associated with several anti-influenza benefits,

including reduced risk influenza and the increase in vaccine efficacy rates

[21,23,30,31].

After moderate

intensity physical activity, an increase in the count of neutrophil and natural

killer cells (NK) is detected, and an increase in the salivary concentrations

of IgA [42,43]. Moderate physical activity increases stress hormones and, thus,

reduce excessive inflammation [43] and lead to increased immunity against viral

infections by altering the responses of Th1/Th2 cells [42].

To study this

situation more deeply, Song et al. [14] summarized the current literature on

the effects of exercise on influenza or pneumonia in the elderly to determine

the appropriate exercise that contributes to beneficial clinical outcomes for

this population. The results confirmed that aerobic exercise with moderate

intensity can help to reduce the risk of influenza-related infection, improve

immune responses to influenza and pneumonia vaccine in the elderly. Even

traditional Asian martial arts can also contribute to some related benefits.

Impact of COVID-19 on physical inactivity and physical

and mental health

The COVID-19

pandemic appears to have a major impact on physical activity behaviors

worldwide, forcing people to remain self-isolated in their homes for a period.

These acts will negatively affect people's physical activity behaviors

[25,32,33].

Currently,

the world lives with two concomitant pandemics. Although of a different nature,

the physical inactivity pandemic has been present in society for some years and

becomes even more worrying, given that COVID-19 is making people move less than

before, bringing the risk of worsening the situation with resuming to

normality. The interaction between the current risks of health complications

and the mortality rates associated with COVID-19 and the current state of

physical inactivity and physical inactivity cannot be ignored. Therefore,

global society needs to establish great effort to encourage people to engage in

physical activity after COVID-19, or at the very least to maintain at the level

they had before the pandemic. In this way, they will avoid a possible vicious

cycle in which current and high standards of physical inactivity and sedentary

behaviors worsen the impact of future pandemics [34].

The impact of a

sedentary lifestyle may be less for children and young adults, but much more

decisive for at-risk populations, which include older people (± 60 years),

presenting obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, history of

smoking, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [6].

Because of the

higher risk of COVID-19 infection, older people need to stay at home, making

physical activities during quarantine crucial to avoid sedentary lifestyle [35].

How will the elderly maintain their independence and mental wellbeing after

ending the quarantine if they have no appropriate promotion of physical

activity at home?

In this sense,

Goethals et al. [35] conducted a qualitative study to assess the impact

of quarantine on the program of the French Federation of Physical Education and

Voluntary Gymnastics and on the physical and mental wellbeing of older adults.

They also looked at the alternatives that could be offered to this population

to avoid a sedentary lifestyle. The research was carried out using

semi-structured interviews with managers of the PA programs for the elderly and

sports coaches who supervise these programs. The results of the study suggested

that COVID-19 affected the number of PA programs in the elderly groups even

before the quarantine measures were implemented. It was found that the elderly

expressed the need to exercise at home during quarantine despite the decline in

participation in physical activities before isolation measures due to fear of

contact with infected people. Therefore, the authors recommend assistance to

help the elderly to engage in simple and safe ways to remain physically active

during the pandemic and a national policy to support this population to

exercise at home [35].

For this

population, Jiménez-Pavón et al. [13] propose a

more precise prescription and recommendation to ensure an appropriate exercise

program, which is designed to maintain or improve the main components of

health-related physical fitness during COVID-19 through regular participation

in moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, muscle strengthening, balance,

coordination, and stretching activities.

Another risk

group, vulnerable to respiratory infection and adverse effects of COVID-19 are

obese, overweight, and insulin-resistant people with diabetes. These

individuals usually have low-grade chronic inflammation characterized by

elevated levels of various pro-inflammatory cytokines. Considering that the

COVID-19 progression depends largely on the individual's initial health status

and the immune response triggered by the infection, it is suggested that

previous physical training and high levels of cardiorespiratory fitness by

moderate intensity aerobic training are probably immunoprotective

in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, especially those with these chronic

comorbidities [6]. Thus, as exercise of moderate intensity can increase the

immune response and reduce the patterns of pro-inflammatory cytokines, it is

recommended for this population to carry out moderate regular physical activity

in a safe environment combined with an adequate diet to promote beneficial

effects on immune function and health maintenance avoiding the complications of

COVID-19 [36].

Recommendations on regular physical activity during

the COVID-19 pandemic

Due to the

global increase in the pandemic, it is essential to follow the measures of

infection control and safety. Thus, staying at home is a fundamental safety

principle that can limit the spread of infections [26]. However, staying at

home for a long time can intensify behaviors that lead to a sedentary lifestyle

and contribute to anxiety and depression, which can result in a series of

chronic health conditions [26,33]. For this reason, it is important that the

population be informed about the need to reduce sedentary behavior during the

period of social isolation [37].

In this regard,

maintaining regular physical activity and exercising routinely in a safe home

environment is an important strategy for a healthy life during the coronavirus

pandemic [26]. The same authors, following the guidelines of the US Department

of Health and Human Services, recommend at least 30 minutes of moderate

physical activity every day and/or at least 20 min of vigorous physical

activity every other day, in addition to regular strengthening exercise [26].

It is suggested that children, the elderly, and people who have already had

symptoms of coronavirus infection or are susceptible to chronic cardiovascular

or pulmonary disease should seek guidance from specialized health professionals

on the safety of physical activity [26,31].

Cheval et al.

[38] found that changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviors during

lockdown are associated with changes in physical and mental health. The authors

assessed differences in physical activity and sedentary behaviors before and

during the lockdown in a total of 267 (1st wave of COVID-19) and 110

participants (2nd wave of COVID-19) who live in France or Switzerland. Based on

the results, the authors reinforce that ensuring sufficient levels of physical

activity and reducing sedentary time during the lockdown can benefit health of

individuals.

It is

important to underline the reasons why regular exercise should not be

interrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic. For this purpose, Raiol

et al. [25] studied the beneficial effects of exercise for people in

social distance, addressing aspects of immunity, disease control, functional

capacity, and mental health. After analyzing the literature, the authors

suggested that, during social distance, physical exercises should be performed

at home or in open-air places without crowds. The frequency should be 5-7 days

a week for aerobic exercises and, at least, 2-3 days a week for muscle

strengthening exercises, both with moderate intensity, in

order to maximize the positive effects on the immune system.

Based on proven

evidence, Laddu et al. [19] extend the benefits of regular physical

activity to improving immune function and reducing the risk, duration, or

severity of viral infections. Therefore, they recommend the usual practice (~

150 min per week) of moderate intensity physical exercises to obtain ideal

immune support. However, evidence strengthens that even acute PA sessions can

protect people from viral infections [45], agreeing with the view that moving

daily in a structured manner can optimize immune system functions and prevent

or mitigate the severity of infection, especially among vulnerable and

immunocompromised populations.

Consistent with

available evidence and the similarity of some of the signs and/or symptoms of

COVID-19 with the H1N1 virus, moderate exercise may be recommended during the

outbreak for healthy or asymptomatic individuals. People with mild symptoms of

the upper respiratory tract (eg, runny nose, nasal

congestion, mild sore throat) may exercise lightly with precautions [30]. It is

worth mentioning that prolonged exercise programs or high intensity training

without adequate recovery can cause immunodepression and increase

susceptibility to pathogens and infectious diseases [19,23,30,31,41,42,45,46].

Oliveira Neto et

al. [39] proposed an exercise prescription during the COVID-19 pandemic,

integrating the physiological and psychobiological aspects, considering the

barriers confronted by the population in the face of social isolation

worldwide. They recommend a prescription that encourages at least 150 minutes

of aerobic exercise with moderate intensity complemented with strength

exercises for the main muscle groups. The authors emphasize the importance of

behavioral and motivational aspects alongside physiological variables as one of

the major challenges, given the need to train with little or no face-to-face

supervision, which can increase behavioral difficulties (for example, habit) to

exercise.

In conformity

with the WHO recommendations, Jakobsson et al. [33] highlight the

benefits of PA during the COVID-19 pandemic in the respect that “doing

something is better than doing nothing”. They also establish the following

recommendations: avoid prolonged sitting time; reduce sedentary lifestyle with

brief active breaks during the day; accumulate at least 150 minutes of moderate

intensity PA or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity per week; use training

applications to monitor PA and/or follow online exercise classes to motivate

exercise; include cardiovascular and muscle strengthening exercises; always be

cautious and aware of your own limitations, and do not exercise with infection

symptoms.

Hammami et

al. [32] present useful information for daily home PA for sedentary people

during the pandemic, extending the recommendations to children and adolescents.

Children and young people (5 to 17 years old) should perform 60 min/week of

daily PA with aerobic exercises of moderate to vigorous intensity in addition

to muscle and bone strengthening three times a week. For adults and the elderly

(>17 years), they recommend 75 min/week of daily PA with aerobic exercises

of vigorous intensity or 150 min/week of moderate aerobic intensity, with

muscle and bone strengthening twice a week. They also recommend that people

remain active by exercising at home. In this respect, different types of

activities can be scheduled, including aerobic exercises using stationary bikes

or rowing ergometers, strength training with body weight, exercises based on

dance, and active games.

Fallon et al.

[18] increase the types of exercises to be performed at home during the

COVID-19 pandemic. A simple search on the Internet or YouTube will reveal many

home programs for dance, aerobics, yoga, Pilates, strength, and stretching

exercises. Aerobic exercise can be facilitated using stairs and inclines;

running on the spot; home bikes, treadmills; or laps around the backyard pool.

The strengthening activity can be performed through bodyweight exercises such

as squats, push-ups, abdominal work, and stair or inclination calf raises are

also useful. Simple household items such as full water bottles and cans or food

packages can be used as overload. However, Simpson and Katisanis

[23] maintain that it is probably unnecessary to use specialized technology and

equipment to remain physically active during the coronavirus outbreak, since

exercising at home or outdoors through fast walks, climbing stairs, working in

the yard/house and/or playing active games can be equally effective using

online exercise platforms in this period.

To better cope

with the social isolation, Ferreira et al. [11] proposes to the

population some behaviors and attitudes that will help in maintaining an active

life and improving physical and mental health: performing pleasurable physical

activities, exploring the best available spaces and materials; perform routine

activities such as cleaning, maintenance and organization of domestic spaces;

playing and exercising with children, adolescents, and pets (so that energy

expenditure is higher than in the resting condition); avoid sedentary behavior,

alternating sitting or lying down with periods of PA, reducing the time spent

using electronic devices [37], and allowing a few minutes for stretching,

relaxation, and meditation activities [11].

Due to the

increased need for exercise during the quarantine, Jiménez-Pavón

et al. [13] made a critical analysis of the most appropriate

recommendations for exercising, especially for the elderly population and

adjusted and increased the international recommendations on PA for the current

situation. The authors suggest an increase to 200 to 400 minutes per week,

spread over 5 to 7 days to compensate for the decrease in normal daily levels

of PA. In addition, a minimum of 2-3 days a week of resistance training may be

recommended, in addition to daily stretching routines and balance and

coordination exercises at least twice a week, which are distributed among the

different training days. Pitanga et al. [37]

recommend the duration of approximately 30 to 60 minutes a day for each

exercise session. The control of exercise intensity is crucial to avoid harmful

effects and promote the improvement of the immune system. For this purpose,

during quarantine times, moderate intensity (40 to 60% of heart rate reserve or

65 to 75% of maximum heart rate) should be the best option, especially for the

elderly [13].

Rodrígues et

al. [15] analyzed the recommendations for performing PA in health

institutions during the pandemic period, inside and outside Spain. In general,

all entities provide the same general recommendations: stay active at home,

take short breaks, and avoid a sedentary lifestyle. They also reinforce that,

to remain active during lockdown, the population must carry out multifunctional

programs for the whole body, which include aerobic exercises, muscle

strengthening, balance and stretching, in addition to cognitive tasks that are

strongly recommended for the elderly. However, none of the institutions makes

specific recommendations about series and repetitions, intensity, or frequency,

and most recommend the use of online classes or mobile applications [15].

Considering PA

outside the home environment, publications based on scientifically sound

findings and observing the current rules of social distance recommend the

permission of moderate outdoor sports activities (such as running, walking, and

cycling) and park trails, hiking trails, and forest roads on easy terrain [8,48].

The results of a recent study on the aerodynamic effects of movement carried

out through a computer simulation of fluid dynamics, in the absence of head

wind, tail wind, and cross wind, point to the need for additional precautions

of social distance for outdoors activities and sports. Distances of 05 meters

must be kept when walking fast at 4 km/h and 10 meters when running at 14.4

km/h. In addition, people should avoid walking or running directly behind the

main person and keep a distance of 1.5 m in an

alternating or side-by-side arrangement [49].

Some indirect

evidence shows that moderate PA can be recommended as a non-pharmacological,

inexpensive, and feasible way of facing COVID-19 infection. However,

high-intensity exercise can be harmful and exacerbate the infection, especially

in patients at risk. This is probably due to the oxidant production and the

suppression of the immune system. Thus, the recommendation of these exercises

needs further investigation [40,47]. The results of a recent systematic review

have shown that long, intense exercise can lead to higher levels of

inflammatory mediators, which can lead to an increased risk of injury and

chronic inflammation. However, moderate or vigorous

exercise with appropriate rest periods can be significantly beneficial for

improving immune function [47].

According to Zhu

[31], it is safe to exercise during the coronavirus outbreak. However, there

may be some additional precautions to reduce the risk of transmission. For

social exercisers, it is opportune to limit exposure to symptomatic exercise

partners and in some cases, it may be appropriate to use a mask during exercise

to avoid exposure.

Azizi et al.

[50] present some recommendations to athletes and non-athletes during the COVID-19

pandemic to maintain good health conditions for a future return to activities:

regular physical activity of moderate intensity avoiding extreme physical

efforts; aerobic or resistance activities in safe environments, respecting the

recommended social distance; disinfection of the training equipment; no

physical activity in case of fever or other suggestive symptoms; choose to

perform physical activity at home through safe, simple physical exercises that

are easy to perform and adapt; avoid drinking alcohol, and maintain quality

sleep.

Specifically

related to strength and power training, with equipment and load variety, in

order to limit access to training sites due to the COVID19 pandemic, Guimarães-Ferreira and Bocalini

[51] present practical recommendations for strength training in the home

environment during the pandemic to maintain physical fitness and reduce the

deleterious effects of detraining. These authors recommend performing exercises

using your own body weight, household items and, when accessible, dumbbells,

and elastic bands. For low loads (30-50% of 1 maximum repetition), the series

should be performed to concentric failure to optimize gains in strength and

muscle mass. Exercises should be performed on most days of the week (>5 days/week),

in combination with domestic and leisure activities that involve the movement

of the whole body. To maintain and/or develop muscle power, ballistic movements

should be included with or without external loads.

Recommendations on physical activity after COVID-19

An important

situation to be discussed is the maintenance or return to PA during or after an

upper respiratory tract infection. Halabchi et al.

[1] are based on evidence about the neck check rule. If symptoms of upper

respiratory tract infection are limited to the neck, including coughing,

sneezing, and sore throat, the individual is asked to run for 10 minutes. If

the general condition and signs are deteriorated, physical activity should be

prohibited until full recovery. If the conditions do not change after 10

minutes of running, the person may return to physical activity of low to

moderate intensity (below 80% of VO2max). However, due to the new

COVID-19 characteristics and its negative effect on the immune system and rare

cardiac complications, including myocarditis, more caution is required

regarding the continuation of exercise in symptomatic patients [1].

Therefore,

people who have already been infected with influenza, severe acute respiratory

syndrome (SARS), or the current COVID-19 can exercise moderately as long as

they have mild symptoms of the upper respiratory tract (for example, runny

nose, nasal congestion, mild sore throat). However, physical exercise is not

recommended for people with symptoms of severe sore throat, body aches,

shortness of breath, general fatigue, chest cough or fever [30]. It is

recommended to seek medical attention if you experience these symptoms [31]. In

general, recovery from respiratory viral infections takes 2 to 3 weeks, which

corresponds to the time for the immune system to generate cytotoxic T cells

needed to clear the virus from infected cells. After this period, when the

symptoms disappear, it is safe to start exercising regularly in a progressive

manner [31].

With regard to

school-age children and adolescents returning to PA after COVID-19, Chen et

al. [41] point out that with the resumption of school activities, public

health need to ensure that all children and youth effectively overcome the

imposed restrictions that limited exercise. Children should participate in the

recommended levels of PA during the school day, including the time they spend

in physical education classes. This return to PA can help students recover from

the stress and anxiety they experienced while in quarantine. Thus, restoration

of daily physical and sports activities must be progressive, starting with

short periods of activities more attractive to children and young people and

gradually increasing the number of days and the amount of time for

participation, so that eventually it will be enough to meet the guidelines,

minimizing the risk of injury after lockdown [41].

There are two

limitations in this research. First, the absence of randomized clinical trials

and the scarcity of studies with experimental design, with little

methodological rigor on the current topic, making it impossible to determine

the validity of methods and results. Second, it refers to publications about

different populations due to the emergence of the topic under study.

Conclusion

Regarding the

effects of exercise on viral respiratory infections, the evidence points to the

positive effects of exercising in an appropriate manner with moderate intensity

in the responses of the immune system, which may contribute to the reduction of

inflammation and the risk of infection.

With respect to

the impact of COVID-19 related to physical inactivity, physical health and

mental wellbeing, the results show a negative impact of physical inactivity and

sedentary lifestyle during and after the pandemic, with a greater effect on populations

at risk, especially the elderly.

In relation to

the recommendations on regular PA during COVID-19, it is evident that moving

daily in a structured way, by exercising, can optimize the functions of the

immune system and prevent or mitigate the severity of the infection, especially

in the most vulnerable populations. In this sense, most recommendations are for

PA of moderate intensity during the period of social isolation. Aerobic

exercises 5-7 days a week are suggested, muscle strengthening exercises at

least 2-3 days a week, and coordination, balance, and mobility exercises.

Prolonged exercise programs or high intensity training without adequate

recovery to avoid immunosuppression and greater susceptibility to infections

are contraindicated. Physical outdoor activities are recommended if additional

precautions for social distance are taken.

The analysis of

the evidence in the present study shows a lack of publications that focus on

determining the intensity of exercises during the pandemic, as well as specific

recommendations on series and repetitions. Caution is required regarding the

return, maintenance, and continuity of PA after COVID-19, mainly due to the

negative effect on the immune system and cardiac complications caused by the virus.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest have been reported for this

article.

Financing source

This

study was financed in part by the Coordenação de

Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001.

Authors´s

contributions

Conception and design of the research:

Nogueira CJ, Cortez AL. Data collection: Nogueira CJ, Cortez AL, Leal SMO. Analysis

and interpretation of data: Nogueira CJ, Cortez AL. Obtaining financing: Dantas EHM. Writing of the manuscript: Nogueira CJ,

Cortez AL, Leal SMO, Dantas EHM. Critical revision

of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Nogueira CJ, Cortez

AL, Leal SMO, Dantas EHM.

References

- Halabchi F,

Ahmadinejad Z, Selk-Ghaffari M. COVID-19 Epidemic:

exercise or not to exercise; that is the question! Asian J Sports Med

2020;11(1). doi: 10.5812/asjsm.102630 [Crossref]

- Silva CMS, Andrade ADN, Nepomuceno B, Xavier DS, Lima E, Gonzalez I et al. Evidence-based physiotherapy and functionality in adult and pediatric patients with COVID-19. J Hum Growth Dev 2020;30(1):148-55. doi: 10.7322/jhgd.v30.10086 [Crossref]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization.

Director-General’s remarks at the media briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February

2020 [Internet]. 2020 [cited

2020 Maio 8]. p. 1-5. Available from:

https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020

- Bogoch II, Watts A, Thomas-Bachli A, Huber C, Kraemer MUG, Khan K. Potential for global spread of a novel coronavirus from China. J Travel Med 2020;13;27(2):1-3. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa011 [Crossref]

- Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 2020;395(10224):565-74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8 [Crossref]

- Zbinden-Foncea H, Francaux M, Deldicque L, Hawley JA. Does high cardiorespiratory fitness confer some protection against pro-inflammatory responses after infection by SARS-CoV-2? Obesity 2020;oby.22849. doi: 10.1002/oby.22849 [Crossref]

- Di Gennaro F, Pizzol D, Marotta C, Antunes M, Racalbuto V, Veronese N et al. Coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) current status and future perspectives: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(8):2690. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082690 [Crossref]

- Frühauf A, Schnitzer M, Schobersberger W, Weiss G, Kopp M. Jogging, nordic walking and going for a walk - inter-disciplinary recommendations to keep people physically active in times of the covid-19 lockdown in Tyrol, Austria. Curr Issues Sport Sci 2020. doi: 10.15203/CISS_2020.100 [Crossref]

- Mann RH, Clift BC, Boykoff J, Bekker S. Athletes as community; athletes in community: covid-19, sporting mega-events and athlete health protection. Br J Sports Med 2020;54(18). doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102433 [Crossref]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020;395(10223):497-506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [Crossref]

- Ferreira MJ, Irigoyen MC, Consolim-Colombo F, Saraiva JFK, De Angelis K. Vida Fisicamente ativa como medida de enfrentamento ao COVID-19. Arq Bras Cardiol 2020;114(4):601-02. doi: 10.36660/abc.20200235 [Crossref]

- Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, Pu K, Chen Z, Guo Q et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2020;94:91-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017 [Crossref]

- Jiménez-Pavón D, Carbonell-Baeza A, Lavie CJ. Physical exercise as therapy to fight against the mental and physical consequences of COVID-19 quarantine: Special focus in older people. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2020;63(3);386-88. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.03.009 [Crossref]

- Song Y, Ren F, Sun D, Wang M, Baker JS, István B, et al. Benefits of exercise on influenza or pneumonia in older adults: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(8):2655. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082655 [Crossref]

- Rodríguez MA, Crespo I, Olmedillas

H. Ejercitarse en tiempos del COVID-19: ¿qué recomiendan los expertos hacer entre cuatro paredes? Rev Española Cardiol

2020;73(7):527-29. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2020.04.002 [Crossref]

- Carda S, Invernizzi M, Bavikatte G, Bensmaïl [Crossref] D, Bianchi F, Deltombe T, et al. The role of physical and rehabilitation medicine in the COVID-19 pandemic: the clinician’s view. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2020;63(6)554-56. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2020.04.001 [Crossref]

- Campbell JP, Turner JE. Debunking the myth of exercise-induced immune suppression: redefining the impact of exercise on immunological health across the lifespan. Front Immunol 2018;9(4):1-21. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00648 [Crossref]

- Fallon K. Exercise in the time of COVID-19. Aust J Gen Pract 2020;49. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-COVID-13 [Crossref]

- Laddu DR, Lavie CJ, Phillips SA, Arena R. Physical activity for immunity protection: Inoculating populations with healthy living medicine in preparation for the next pandemic. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2020;40:4-6. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.006 [Crossref]

- Luan X, Tian X, Zhang H, Huang R, Li N, Chen P, et al.

Exercise as a prescription for patients with various diseases. J Sport Heal Sci

2019;8(5):422-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2019.04.002 [Crossref]

- Simpson RJ, Campbell JP, Gleeson M, Krüger K, Nieman DC, Pyne DB et al. Can exercise affect immune function to increase susceptibility to infection? Exerc Immunol Rev 2020;26:8-22.Available from: http://eir-isei.de/2020/eir-2020-008-article.pdf

- Wu Y, Ho W, Huang Y, Jin D-Y, Li S, Liu S-L et al. SARS-CoV-2 is an appropriate name for the new coronavirus. Lancet 2020;395(10228):949–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30557-2 [Crossref]

- Simpson RJ, Katsanis E. The immunological case for staying active during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav Immun 2020:87:6-7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.041 [Crossref]

- Medicine AAC of S. Staying physically active during

the COVID-19 Pandemic 2020 [cited 2020 May 8]. p.2.

Available from:

https://www.acsm.org/read-research/newsroom/news-releases/news-detail/2020/03/16/staying-physically-active-during-covid-19-pandemic

- Raiol RA. Praticar exercícios físicos é fundamental para a saúde física e mental durante a pandemia da COVID-19. Brazilian Journal of Health Review 2020;3:2804-13. doi: 10.34119/bjhrv3n2-124 [Crossref]

- Chen P, Mao L, Nassis GP, Harmer P, Ainsworth BE, Li F. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): The need to maintain regular physical activity while taking precautions. J Sport Heal Sci 2020;9(2):103-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.02.001 [Crossref]

- Souza MT, Silva MD, Carvalho RD. Integrative review: what is it? How to do it? Einstein (São Paulo) 2010;8(1):102-6. http://doi.org/10.1590/s1679-45082010rw1134 [Crossref]

- Beyea SC. Writing an integrative review. AORN J 1998;67(4):877-80. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)62653-7 [Crossref]

- Moher D, Altman DG, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J. PRISMA Statement. Epidemiology 2011;22(1):128. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181fe7825 [Crossref]

- Shirvani H, Rostamkhani F. Exercise considerations during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak: A narrative review. J Mil Med 2020;22(2):161-8. doi: 10.30491/JMM.22.2.161 [Crossref]

- Zhu W. Should, and how can, exercise be done during a coronavirus outbreak? An interview with Dr. Jeffrey A. Woods J Sport Heal Sci 2020;9(2):105-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.01.005 [Crossref]

- Hammami A, Harrabi B, Mohr M, Krustrup P. Physical activity and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): specific recommendations for home-based physical training. Manag Sport Leis 2020;0(0):1-6. doi: 10.1080/23750472.2020.1757494 [Crossref]

- Jakobsson J, Malm C, Furberg M, Ekelund U, Svensson M. Physical activity during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: prevention of a decline in metabolic and immunological functions. Front Sport Act Living 30 abr 2020. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2020.00057 [Crossref]

- Hall G, Laddu DR, Phillips SA, Lavie CJ, Arena R. A tale of two pandemics: How will COVID-19 and global trends in physical inactivity and sedentary behavior affect one another? Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2020;40:4-6. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.005 [Crossref]

- Goethals L, Barth N, Guyot J, Hupin D, Celarier T. Need for a physical activity promotion strategy for older adults living at home during quarantine due to Table of Contents. JMIR Aging 2020;3(1):e19007. doi: 10.2196/19007 [Crossref]

- Azizi GG, Orsini M, Dortas Júnior SD, Cerbino SA. Obesidade e imunologia do exercício: implicações em tempos de pandemia de COVID-19. Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc 2020;19(2supl):S35-S39. doi: 10.33233/rbfe.v19i2.4023 [Crossref]

- Pitanga FJG, Beck CC, Pitanga CPS. Atividade física e redução do comportamento sedentário durante a pandemia do Coronavírus. Arq Bras Cardiol 2020;114(6):1058-60. doi: 10.36660/abc.20200238 [Crossref]

- Cheval B, Sivaramakrishnan H, Maltagliati S, Fessler L, Forestier C, Sarrazin P, et al. Relationships between changes in self-reported physical activity and sedentary behaviours and health during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in France and Switzerland. SportRxiv 25 apr 2020. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2020.1841396 [Crossref]

- Oliveira Neto L, Elsangedy HM, Tavares VDO, Teixeira CVLS, Behm DG DS-GM. #TreineEmCasa – Treinamento físico em casa durante a pandemia do COVID-19 (SARS-COV2): abordagem fisiológica e comportamental. Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc 2020;19(2):S9-S19. doi: 10.33233/rbfe.v19i2.4006 [Crossref]

- Rahmati-Ahmadabad S, Hosseini F. Exercise against SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): Does workout intensity matter? (A mini review of some indirect evidence related to obesity). Obes Med 2020;2:100245. doi: 10.1016/j.obmed.2020.100245 [Crossref]

- Chen P, Mao L, Nassis GP, Harmer P, Ainsworth BE, Li F. Returning Chinese school-aged children and adolescents to physical activity in the wake of COVID-19: Actions and precautions. J Sport Heal Sci 2020;9(4):322-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.04.003 [Crossref]

- Martin SA, Pence BD, Woods JA. Exercise and respiratory tract viral infections. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2009;37(4):157-64. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181b7b57b [Crossref]

- Harris MD. Infectious disease in athletes. Curr Sports Med Rep 2011;10(2):84-9. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e3182142381 [Crossref]

- Sallis J. A

call to action: physical activity and COVID-19. EIM Blog. American College of

Sports Medicine. [cited

2020 Apr 16]. Available from:

https://www.exerciseismedicine.org/support_page.php/stories/?b=896

- Dimitrov S, Hulteng E, Hong S. Inflammation and exercise: Inhibition of monocytic intracellular TNF production by acute exercise via b 2 -adrenergic activation. Brain Behav Immun 2017;61:60-8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.12.017 [Crossref]

- Ahmadinejad Z, Alijani N, Mansori S, Ziaee V. Common sports-related infections: a review on clinical pictures, management and time to return to sports. Asian J Sports Med 2014;5(1):1-9. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.102630 [Crossref]

- Cerqueira E, Marinho DA, Neiva HP, Lourenço O. Inflammatory effects of high and moderate intensity exercise - a systematic review. Front Physiol 202;9(10):1-14. doi: 10.1016/j.obmed.2020.100245 [Crossref]

- Nyenhuis SM, Greiwe J, Zeiger JS, Nanda A, Cooke A. Exercise and Fitness in the age of social distancing during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;8(7):2152-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.039 [Crossref]

- Blocken B, Malizia F, van Druenen T, Marchal T. Towards aerodynamically equivalent COVID19 1.5 m

social distancing for walking and running [Internet]. Urban Physics 2020

[cited 2020 may 11]. Available from: http://www.urbanphysics.net/Social Distancing v20_White_Paper.pdf

- Azizi GG, Orsini M, Dortas Júnior SD, Vieira PC, Carvalho RS, Pires CSR et al. COVID-19 e atividade física: qual a relação entre a imunologia do exercício e a atual pandemia? Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc 2020;19(2supl):S20-S29. doi: 10.33233/rbfe.v19i2.4115 [Crossref]

- Guimarães-Ferreira L, Bocalini DS. Atenuação do destreinamento durante a pandemia de COVID-19: considerações práticas para o treinamento de força e potência em ambiente doméstico. Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc 2020;19(2supl):S47-S55. doi: 10.33233/rbfe.v19i2.4112 [Crossref]