Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc 2020;19(4):255-57

EDITORIAL

Idiosyncrasy

in science: an idea forgotten or not understood?

Jefferson Petto1,2,3,4,

Thiago Bouças Duarte3,5,6, Taissa Argolo

Jesus3

1ACTUS-CORDIOS

Reabilitação Cardiovascular, Respiratória e Metabólica, Salvador, BA, Brasil

2Centro Universitário

Social da Bahia, Salvador, BA, Brasil

3Faculdade do Centro Oeste

Paulista, Bauru, SP, Brasil

4Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública, Salvador, BA, Brasil

5Hospital Português da Bahia, Salvador, BA, Brasil

6Universidade Salvador –

Unifacs, Salvador, BA, Brasil

Received

on: August 5, 2020; Accepted on: August 21, 2020.

Corresponding author: Jefferson Petto, Av.

Anita Garibaldi, 1815, CME, Sala 13 Ondina 40170-130 Salvador BA

Jefferson

Petto: gfpec@outlook.com

Thiago

Bouças Duarte thiago_fisio@yahoo.com.br

Taissa Argolo

Jesus: taissa_argolo@hotmail.com

The idea of idiosyncrasy (idiosugkrasía)

emerged in Greek civilization and referred to the individual's peculiar

behavioral condition [1]. In current medicine, the term refers to "the

particular predisposition of the organism that causes an individual to react

personally to the influence of external agents, such as food and drugs"

[1].

Although most people intuitively think that for each action imposed the

reaction can be different, in the plurality of times, the prevailing thought is

that of generalization. This does not seem to be different in science and

clinical practice. The understanding that external and internal factors will be

determining the response to a treatment should be the basis, both in research

and in health practice, however it is not. Certainly, there are several reasons

for this behavior and one of them is the misinterpretation of the scientific

text.

We know that the most widely read section of a scientific article is the

summary, and the most widely read summary is its conclusion. The conclusion

points out “the authors' position or solution based on the arguments presented;

sometimes it suggests unfolding” [2]. Therefore, it answers in a conceptual and

generic way the question that generated the objective of the work. Not

intentionally, but the idiosyncrasy in this text is omitted, because it is

inherent in scientific writing.

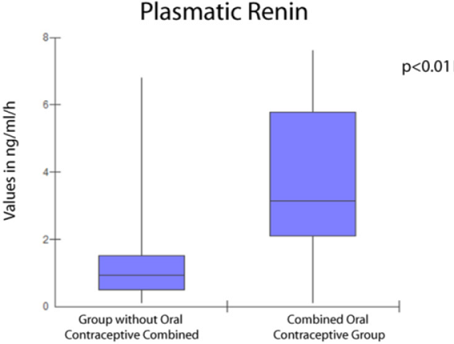

For example, we recently published an article entitled “Plasma Renin in

Women Using and Not Using Combined Oral Contraceptive”, in which we tested the

hypothesis that women using combined oral contraceptive (COC) have plasma renin

values different from their counterparts that do not use this drug [3]. In

parallel, we also evaluated Reactive Protein C (RPC). It was an observational

cross-sectional study. Figure 1 shows the results of this study in relation to

plasma renin. As you can see, we see that the group using COC has plasma renin

values statistically higher than the group without COC. What is our conclusion?

I report: “Women using COC have higher serum levels of plasma renin and

C-Reactive Protein than women who do not use this drug. This points to the

possibility that this population has a higher risk of developing systemic

arterial hypertension in the long term, which associated with subclinical

inflammation can increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases” [3].

However, it is also possible to observe in figure 1, that not all women

using COC had higher renin values than the group without COC and that the

opposite is also likely, especially in a non-parametric distribution like this.

That is, although the conclusion is based on a well-performed statistical

analysis, it is necessary to understand that the fact that we found a

statistical difference between the groups does not mean that all the volunteers

in the sample behaved in the same way.

Figure

1 - Median and quartile intervals of the groups with

and without combined oral contraceptives

If a study shows that high-intensity exercise was beneficial for

patients with Ischemic Heart Failure with Intermediate Ejection Fraction, it

does not mean that everyone with this clinical condition will benefit. Physical

exercise is a therapy that, like any other, can have a neutral, positive or

negative effect. That is why understanding health idiosyncrasy is so important.

Knowing that our patient can respond differently to a treatment, even if the

evidence indicates that it is safe and effective, keeps our reasoning open to

changes that are necessary during the follow-up.

Therefore, it is imperative for quality praxis that the professional

uses the knowledge of science with good wisdom, interpreting it properly and

using the knowledge available considering the clinical, social and biological

condition of each patient or client. Scientific evidence provides us with a

basis for a better-founded therapeutic direction, but it does not tell us

exactly how we should conduct our intervention in an airtight manner.

Understanding and applying the idea of idiosyncrasy frees us from a general

protocol, from the evaluation, the preparation of the prognosis, the initial

prescription to the evolution of the treatment. No treatment is 100% foolproof

or 100% effective.

Corroborating this thought, there is in biostatistics what we call NNT

(number needed to treat), number of individuals treated so that the benefit of

a given intervention occurs in an individual. For example, for individuals

after myocardial infarction, it is necessary to treat 842 patients with

beta-blockers in order to avoid death (NNT 842). Considering Cardiac

Rehabilitation, the NNT for individuals after myocardial infarction is 66 [4].

So, will all post-myocardial infarction patients who enter a Cardiac

Rehabilitation program have the benefit of increased survival? The answer is

no. Because despite the studies pointing out that Cardiac Rehabilitation

increases survival, as we can see, we need to treat at least 66 patients to

obtain this response with 1 patient.

In short, correctly interpreting the relationship between idiosyncrasy

and the completion of scientific work, the basis of evidence-based medicine,

will allow us to achieve a better quality of treatment and consequently impact

the health of the community more effectively.

References

- Dicionário Eletrônico

Houaiss da Língua Portuguesa. Consultado em 30 de julho de 2020. Disponível em:

https://houaiss.uol.com.br/corporativo/apps/uol_www/v5-4/html/index.php#1

- Pereira MG. Artigos

científicos: como redigir, publicar e avaliar. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2012. p. 212.

- Oliveira SS, Petto J,

Diogo DP, Santos ACN, Sacramento MS, Ladeia AM. Plasma

renin in women using and not using combined oral contraceptive. Int J Cardiovasc

Sci 2020;33(3):208-14.

https://doi.org/10.36660/ijcs.20180021

- Carvalho T. Diretriz de

reabilitação cardiopulmonar e metabólica: aspectos práticos e

responsabilidades. Arq Bras

Cardiol 2006;86(1):74-82.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0066-782X2006000100011