Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc. 2024;23:e234417

doi: 10.33233/rbfex.v23i1.4417

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Impact of active video games on the glycemic

profile and nutritional

status of adolescents

Impacto do videogame

ativo sobre o perfil glicêmico e o estado nutricional de adolescentes

Anna Larissa Veloso

Guimarães, Renata Cardoso Oliveira, Carla Campos Muniz Medeiros, Danielle Franklin de Carvalho

Universidade Estadual da

Paraíba, Campina Grande, PB, Brazil

Received: April 12, 2022; Accepted:

January 23, 2024.

Correspondence: Renata Cardoso Oliveira: renatacardoso09@hotmail.com

How to

cite

Guimarães ALV,

Oliveira RC, Medeiros CCM, Carvalho DF. Impact of

active video games on the glycemic

profile and nutritional

status of overweight adolescents: a controlled intervention study. Rev Bras Fisiol

Exerc. 2024;e234417. doi: 10.33233/rbfex.v23i1.4417

Abstract

Introduction: The interactive game is an intervention proposal to promote

physical activity, especially among young people, to promote

physical activity. Objective:

To test the

hypothesis of the impact of

physical activity using active video

games (AVG) on the glycidic profile of overweight adolescents. Methods: Controlled intervention study carried out in the second half

of 2018. The sample consisted

of 70 overweight adolescents, distributed in control and experimental groups, aged between

10 and 16 years old, enrolled between the 5th and 9th year of education elementary school II of public schools in the city ofCampina

Grande/PB. Sociodemographic, lifestyle,

nutritional status, and biochemical variables were studied and a gamification strategy was adopted. The data were analyzed in

SPSS 22.0 and the chi-suare and paired t-test were performed, adopting a significance

level of 5%. Results: The intervention improved BMI and reduced abdominal adiposity in adolescents but did not cause significant

changes in the glycemic profile. Conclusion:

The use of active video games to increase physical activity in overweight adolescents in an school environment is an effective

tool to improve the nutritional status of adolescents. Interventions with a longer duration

need to be

evaluated to verify possible effects on the

glycemic profile. This is a viable, low-cost

intervention that takes advantage of technological

resources in line with the interests

of the target population.

Keywords: obesity; adolescent; glycemic profile; physical activity.

Resumo

Introdução: O jogo interativo é uma proposta de intervenção, sobretudo

entre o público jovem, na promoção da atividade física. Objetivo: Testar

a hipotese do impacto da atividade física com uso de

videogame ativo sobre o perfil glicêmico de adolescentes com excesso de peso. Métodos:

Estudo de intervenção controlado realizado no segundo

semestre de 2018. A

amostra foi composta por 70 adolescentes com excesso de peso,

distribuídos nos

grupos controle e experimental, com idade entre 10 e 16 anos,

matriculados

entre o 5º e o 9º ano do ensino fundamental II de escolas

públicas do município

de Campina Grande/PB. Foram estudadas variáveis

sociodemográficas, de estilo de

vida, estado nutricional e bioquímicas e adotou-se une

estratégia de gamificação. Os dados foram

analisados no SPSS 22.0

e foram realizados os testes qui-quadrado e t-pareado, adotando-se um

nível de significância de 5%. Resultados: A

intervenção melhorou o IMC e reduziu a adiposidade abdominal dos adolescentes,

mas não causou alterações significativas sobre o perfil glicêmico. Conclusão:

O uso do videogame ativo para aumentar a atividade física em adolescentes com

excesso de peso em ambiente escolar é uma ferramenta eficaz para melhorar o

estado nutricional de adolescentes. Intervenções com maior tempo de duração

necessitam ser avaliadas para verificar os possíveis efeitos no perfil

glicêmico. Está é uma intervenção viável, de baixo custo e aproveita recursos

tecnológicos em sintonia com interesse da população alvo.

Palavras-chave: obesidade; adolescente; perfil

glicêmico; atividade física.

Introduction

Due to the epidemiological changes that have

occurred, it is believed that there

will be a higher percentage of adolescents with high-adiposity than malnourished adolescents in the coming years [1].

Adolescence is considered the most critical period

for obesity occurrence and, consequently, associated problems, as this phase is

characterized by a low level of

physical activity, the development and consolidation of sedentary behaviors,

and changes in body composition. These facts make this period important for carrying out

intervention and prevention measures [2].

Changes caused by physical exercise

are already predicted in the lipid profile [3], blood glucose, blood pressure [4], and inflammation levels assessed by c-reactive

protein (CRP) in obese individuals.

In a randomized clinical trial [5], which evaluated the impact

of one year

of physical exercise on obese

children and adolescents, beneficial changes were found in glycemic

control (fasting blood glucose) in individuals undergoing the proposed intervention.

In this context, it is necessary to

adopt strategies that motivate children

and adolescents to practice physical

activity, such as active games or exergames — technological games (video games) that require the participant's body movements to function

[6].

This study was developed to

test the hypothesis of the

impact of a physical activity intervention using active video games (AVG) on the glycidic

profile of overweight adolescents.

Methods

A controlled gamified intervention study, with two comparison

groups: “control” - with no intervention, and “experimental” - active video game use, three times a week, for 50 minutes, for eight weeks. A hundred twenty-nine (129) eligible individuals with overweight/obesity were initially evaluated; after applying the exclusion

criteria, 105 remained in the study. With

the record of losses and

dropouts (35), 70 adolescents

made up the

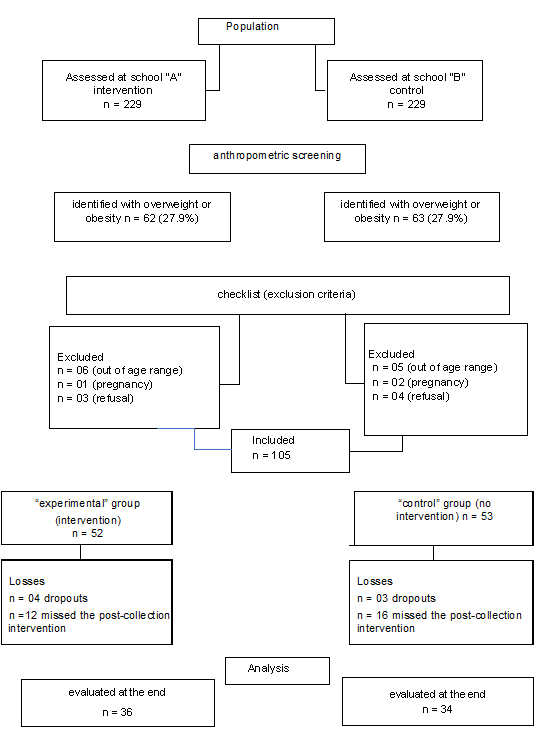

final sample. (Figure 1).

Two public schools in the top quartile of students in Campina Grande/PB were drawn. The intervention was allocated per school, one for the intervention and the other for the control, to avoid bias due to contact between the groups. In the urban area of the city, there are 20 municipal schools, of middle school, in the morning and/or afternoon shifts. The population of this study consists of adolescents aged between 10 and 16 years, 11 months and 29 days, overweight or obese, enrolled between the 5th and 9th year of middle school in the selected schools. In each school, all students who met these criteria were invited to participate in the study, respecting the minimum sample size according to the following parameters: average effect size of 0.75, alpha error of 0.05, and power of 80.0%, totaling a minimum of 29 individuals in each group.

Figure 1 - Flowchart of participants in the study, Campina Grande, PB, 2018

The inclusion criteria used were: adolescents

aged between 10 and 16 years, 11 months and 29 days;

be a student enrolled between the 5th and 9th year of middle

school in the selected schools of Campina Grande/PB; present a nutritional status characterized

as overweight or obesity, according to age and gender,

according to z-score.

Individuals who presented at least

one of the

following situations were excluded from

the study: a condition that did not allow

them to perform

physical activity, such as motor or mental limitations, or diseases in which physical activity could be harmful,

such as exercise-induced bronchospasm and cardiac arrhythmia; patients with hyperthyroidism,

decompensated diabetes mellitus, genetic

syndrome; being on some weight loss treatment; pregnancy, postpartum period or breastfeeding;

active video game user. Cases of individuals who did not collect

blood after the intervention or who gave up

were considered losses.

Variables, procedures and

data collection instruments

Sociodemographic variables (economic class, age, gender, and color), level of physical

activity (active/inactive), nutritional status (overweight or obesity),

and glycidic profile (fasting blood glucose, glycated hemoglobin, and insulin resistance,

using the TyG index) were evaluated. Except for sociodemographic variables, all variables were

evaluated in both groups (experimental and control) before and after the

intervention. Emphasizing that the control

group (without intervention) underwent only blood collections

and questionnaires.

A form was applied

to obtain sociodemographic and lifestyle information. The

assessment of age, gender, and color was based

on criteria from the Brazilian

Institute of Geography and Statistics

[7], the economic class was defined

based on criteria from the

Brazilian Association of Research Companies

[8], and the level of physical

activity was analyzed using the “International Physical Activity Questionnaire” (IPAQ), short version

[9].

Nutritional status was assessed using the body mass index (BMI), constructed from the ratio of

weight (in kg) to the square of

height (in meters), following the recommendations

of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2006), for the

age group, considering: overweight when ≥ +1 BMI

< +2 Z-Score and obesity

when BMI ≥ +2 Z-Score.

Height and weight were measured

in duplicate, considering the average values

of the two

measurements. To measure height, a portable stadiometer, Avanutri® brand, with an accuracy of

0.1 cm, was used; and to identify

the weight, a Tonelli®

digital scale was used, with a capacity

of 150 kg and an accuracy of

0.1 kg. To obtain the measurements, the procedures recommended by the WHO were

followed, and the adolescent had to be

without shoes, accessories, or carrying objects.

Insulin resistance was assessed using

the TyG index calculated from the equation: Tyg

index = [log(fasting triglycerides (mg/dL) x fasting blood glucose (mg/dL)/2. Since there

is no specific cutoff point for insulin resistance by the

TyG index in this age group, the 90th percentile was adopted as a reference, with values equal

to or greater

than it being considered altered [10].

Waist circumference

was measured with the adolescent

in an upright position, with a relaxed abdomen, arms at

their sides, feet together, weight equally supported by both

legs, and breathing normally. The end of the

last rib was located and

marked; then, a measuring tape was positioned horizontally in the midline between

the end of

the last rib and the

iliac crest and maintained so that it remained

in position around the abdomen at the

level of the umbilical scar, allowing the circumference

to be read

to the nearest

millimeter. Values above the 90th percentile were considered increased according to the

International Diabetes Federation (IDF), but with a maximum

limit of 88 cm for girls and 102 for boys, according to the National

Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment

Panel III [11].

Abdominal

adiposity was considered present when the waist

circumference/height ratio was ≥ 0.5 [12].

Intervention and gamification

The intervention was carried out with adolescents in the experimental group. They used the active video

game for 50 minutes, 3

times a week, for 8 weeks.

To carry out the intervention, the XBox 360 platform was used, with

the Kinect accessory

(Microsoft®) to enable the user to

control and interact only with

the command of body movements, making them perform physical

activity. Just Dance (2014 to

2018) was the game selected, as in addition to the fact

that most dances can lead teenagers to achieve moderate intensity of physical

activity, it is also reported in the literature [13] as the one that

arouses the greatest interest among teenagers, in addition to allowing the

intervention to be carried out in a group of four adolescents

at the same

time.

The intervention was carried out in reserved rooms at the

selected school, at times available in the morning and

afternoon shifts, and was supervised and controlled. To this end,

the presence of adolescents on the day

of the activity

was recorded, and heart rate was monitored using

a multilaser® Atrio frequency meter before (to calculate training frequency), during (to monitor exercise intensity) and after the activity

(to assess hemodynamic stability). This equipment is a wireless transmitting heart strap to

the wrist heart monitor.

Measurements were obtained during the intervention period to ensure

that exercise was maintained at moderate intensity.

The activities were carried out in sub-groups of up to

four participants, guided and supervised by physical education

professionals, physiotherapists,

master's students, scientific initiation and/or extension

students linked to the project,

all previously trained.

The

dances used for intervention

were previously selected, including those that could

lead to moderate intensity, and gathered in a block of 10 (GBLOCK). This selection was carried

out by physical education students with experience in using this technology

to promote physical activity.

To increase adolescents' engagement in the intervention activity, a gamification strategy was adopted,

with the creation of new blocks of songs

per week and the development of challenges measured

by a properly calibrated team. The group earned points based on criteria

created by the researchers, such as punctuality, group encouragement, posts about the intervention

on social media, and

individual and group

performance (achieving a number

of stars). There were weekly awards

and a final award for the group that

accumulated the most points at the end of

the intervention.

Adolescent adherence was based on

the frequency of attendance at

physical activity sessions, as well as the performance of supervised activity.

In the control group,

measurements were only taken in the

same periods as in the experimental group.

Data analysis

procedures and ethical aspects

The data were double-entered, initially submitted to Epi Info validation, and analyzed in SPSS 22.0. Normality distribution was assessed using

the Kolmogorov-Sminorv

test.

The chi-square test was

applied to carry out a comparative analysis between sociodemographic characteristics

(economic class: C, D, and E; A and B; gender: male and female; color: white and non-white); level of physical

activity: (not active and active);

nutritional status (overweight

and obese); abdominal adiposity (WC/H ≥ 0.5 and

WC/H < 0.5) and glycidic

profile (fasting blood

glucose ≥ 100.0 and < 100.0 mg/dL; glycated hemoglobin

≥ 5.7 and < 5.7 and

insulin resistance ≥

P90 and < P90 of the TyG index) of adolescents in the two comparison

groups at the beginning of

the study. To evaluate the

effect of the intervention on the measurement

of waist circumference in each group, the paired

t-test was used.

The study was developed

in accordance with Resolution 466/2012 of the National Health Council and was

approved by the Research Ethics

Committee, CAAE: 84019518.3.0000.5187. In accordance with WHO recommendations, it was registered in Clinical Trials

(NCT03532659) and REBEC (RBC-2xn3g6).

Results

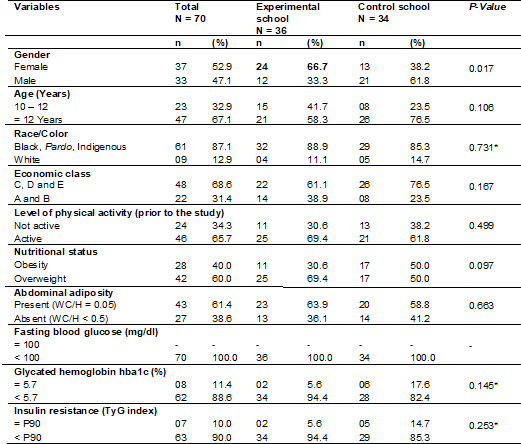

Seventy (70) adolescents

were evaluated, 36 in the experimental group and 34 in the control

group. The two groups were similar in all characteristics, except gender, as there were more boys in the experimental group compared to the

control. The majority of students were

self-reported non-white

(87%) and belonged to economic classes C, D, or E (68.6%).

Regarding lifestyle,

34.3% declared themselves

as non-active, 40% were obese, and 61.4% had excess abdominal adiposity. None had changes in fasting blood glucose. However, 11.4% of the adolescents showed changes in glycated hemoglobin (Table I).

Table I – Comparison of sociodemographic characteristics related to the practice

of physical activity, nutritional status, and glycidic profile of adolescents from “experimental” and “control” schools at baseline. Campina Grande/PB, 2018

WC/H = waist circumference/height ratio; *Fisher's exact test

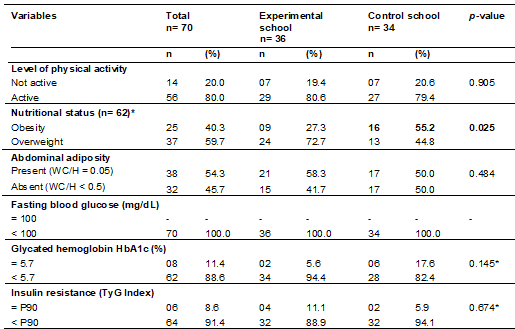

At the end of

the intervention, it was found that

the number of adolescents considered physically active increased to 56 (80.0%), although they were not

associated with the group. Regarding

nutritional status, of the total of 42 adolescents who were overweight, eight were classified

as eutrophic, and cases of obesity were

higher in the control school (n = 16; 55.8%).

It was found that insulin resistance

was no longer associated with the group (Table

II).

WC/H = waist circumference/height ratio; *Eight adolescents reached the nutritional

status of eutrophy; **Fisher's exact test

Discussion

In the present study,

it was observed that obesity was

present in 40.0% of them and abdominal adiposity in 61.4%. Although no change in fasting blood glucose was recorded (above 100 mg/dL), there was

an increase in glycated hemoglobin in 11.4% and insulin resistance

in 10.0%. Of the total,

34.3% were classified as

non-active (inactive or irregularly active).

In a study carried out [13] with 54 obese and

overweight adolescents aged between 15 and 19 years, in which a 20-week intervention was carried out to evaluate whether

the exergame would produce weight

loss. It was concluded that the use of active

video games increased significantly caloric expenditure of these adolescents, in addition to promoting weight loss. Likewise,

an active video game intervention was carried out in overweight children for 24 weeks, and a significant

decrease in BMI was observed among participants [14]. A previous study also carried

out with adolescents no

positive effects of AVG on BMI had been

found. The authors attributed the lack of change

in nutritional status to the intervention time, which was considered

short in the 2017 study (12

weeks); however, longer than that

of the present

study, which was eight weeks,

and managed to record a reduction

in BMI and abdominal adiposity

[15].

This reinforces the need to

evaluate body composition since it is already

known that when starting to

practice physical exercise, muscles begin to develop,

which can affect weight [16]. It also highlights the importance of checking the

intensity of the exercise, in addition to the

frequency and duration, as well as other aspects of

the lifestyle, such as food consumption, aspects that can

affect the outcomes in question [17].

Furthermore, unlike the studies mentioned,

the present study was controlled

and supervised so that the

adolescents carried out the intervention in front of one of

the researchers, who applied gamification

techniques (collaboration, encouragement, and carrying out the activity in groups, for example) to ensure moderate

exercise intensity throughout the execution time (50 minutes). In 2012, Staiano

et al. [14] stated that

cooperative games were capable of producing

greater intrinsic motivation and are more often associated with greater energy

expenditure during the game. A systematic review published in 2019 indicated that cooperative games involving exergames were more attractive to overweight children

and adolescents compared to those

with normal weight, generating greater satisfaction, self-efficacy, and positive expectations, which may favor adherence and commitment

among young people [18].

The ability of exergame

to promote an increase in energy expenditure has been described

in the literature [19]. However, its effects on the metabolic

profile require more attention.

Although

diabetes mellitus (DM) mainly affects individuals from the fourth decad

of life onwards, an increase in incidence has been noticed in children

and young people [20]. A study carried out in some

American states between

2002 and 2012 observed an increase of

7% per year in the prevalence of DM in this population [21].

Although the population in this study is young

and considered normoglycemic, the changes observed in glycated hemoglobin and insulin resistance

may already demonstrate changes in glucose metabolism. Furthermore, this is an

overweight population and it is already

well established that obesity is

associated with a multitude

of metabolic and clinical restrictions,

which result in a greater risk of

developing cardiovascular complications

and metabolic diseases, particularly resistance to insulin

and type 2 diabetes [21].

Methodological differences, especially regarding the method adopted

and the cutoff

points for diagnosing IR using

the TyG index, make it difficult to compare previously published results. One of

the possibilities for not having observed

an impact of the intervention

on the glycidic

profile is that this is an

initially normoglycemic population, and fasting blood glucose is used to

calculate the TyG index, adopted to assess insulin

resistance. The values of triglycerides are also included in the calculation of this index, which can be

reduced during exercise but increase

again immediately after the so-called

“detraining” so that these possible

fluctuations can end up interfering

with the values of the

TyG index [21].

After the intervention with AVG, it was observed that

there was a reduction in AC. This result is similar to that found

in a study [22] in Turkey, which analyzed 50 overweight or obese

adolescents. After an exercise program

using the AVG over 8 weeks, participants' AC values decreased significantly.

Some studies have been

carried out to evaluate the effectiveness

of AVG in combating obesity in children and adolescents [23]. In an experimental study [24] carried out in New Zealand with

20 adolescents, the effects of AVG on the anthropometric

profile and level of physical activity

were evaluated over 12 weeks. After the

intervention, the group showed higher

levels of physical activity and decreased body weight and waist

circumference, corroborating

the results of the present

study.

The use of AVG as an innovative

tool for controlling childhood

obesity has been observed by

health professionals since the benefits

include adherence and increased levels of physical activity,

reduced consumption of low-nutrition foods, and increased

energy expenditure, with direct repercussions on the main

comorbidities associated with childhood obesity [25].

Conclusion

In this study, active

video games did not cause a reduction in glycemic values in overweight and obese adolescents. However, we observed

a reduction in body mass

index and abdominal adiposity

in the sample that played the active

video game. Therefore, the use of active video

games to increase physical activity in adolescents with obesity or overweight

in a school environment can be an

effective tool for a better

lifestyle and changing sedentary habits.

Academic affiliation

Article from

the Master's Thesis by: Anna Larissa Veloso

Guimarães, Master's in Public

Health, State University of Paraíba, 2020.

Conflicts of

interest

There is

no conflict of interest

Funding sources

Ministry of

Science, Technology and Innovation.

Authors' contributions

Conception and

design of the research: Guimarães ALV, Carvalho DF; Data collect:

Guimarães ALV, Carvalho D; Data analysis and interpretation: Guimarães

ALV, Carvalho DF; Manuscript writing: Guimarães ALV, Carvalho DF, Oliveira RC; Critical

review of the manuscript for important intellectual content:

Guimarães ALV, Carvalho DF, Oliveira RC

References

- World Health Organization. (WHO) OMS, OPAS. Obesidade entre crianças e

adolescentes aumentou dez vezes em quatro décadas, revela novo estudo do

Imperial College London e da OMS [internet]. [citado

2020 ago 16]. Disponível em:

https://www.paho.org/braobesidade-entre-criancas-e-adolescentes-aumentou-dez-vezes-em-quatro-decadas-revela-novo-estudo-do-imperial

college-london-e-da-oms

- Alberga AS, Sigal RJ, Goldfield G, Prud HD, KGP. Overweight and obese teenagers: why is adolescence a critical period? Pediatric Obesity.

2012;7(4):261–73. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2011.00046.x [Crossref]

- Prado ES, Dantas EHM. Efeitos dos exercícios físicos aeróbio e de força nas lipoproteínas HDL, LDL e Lipoproteína(a). Arq Bras Cardiol. 2002;79(4);429-33. doi: 10.1590/S0066-782X2002001300013 [Crossref]

- Oka R, Yagi K, Sakurai M, Nakamura K, Nagasawa

S, Miyamoto S, Nohara A, Kawashiri

M, Hayashi M, Takeda O, Yamagishi M. Impact of visceral adipose tissue and subcutaneous

adipose tissue on insulin resistance in middle-aged japanese. J Atheroscler Thromb.

2012;19(1);814–22. doi: 10.5551/jat.12294 [Crossref]

- Blüher S, Panagiotou

G, Petroff D, Markert J,

Wagner A, Klemm T, et al. Effects

of a 1-year exercise and lifestyle intervention

on irisin, adipokines, and inflammatory markers in obese children. Obesity. 2014;22(7):1701–8. doi: 10.1002/oby.20739 [Crossref]

- Biddiss E, Irwin J. Active video

games to promote physical activity in children and youth.

Arch Periatr Adolesc Med.

2010;164(7);664-72. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.104 [Crossref]

- Instituto Brasileiro de

Geografia e Estatística - IBGE [Internet]. Indicadores Sociodemográficos e de

Saúde no Brasil | 2009 [Internet]. [citado 2020 ago

12]. Disponível em:

https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/populacao/9336-indicadores

sociodemograficos-e-de-saude-no-brasil.html

- ABEP. Associação Brasileira

de Empresas de Pesquisa. Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil [Internet].

[citado 2020 ago 12]; Disponível em:

https://www.abep.org/criterio-brasil

- Saucedo MT, Jiménez JR, Macías LAO, Castillo

MV, Hernández RCL, Cortés TLF. Relacion entre el índice de masa corporal, la actividad fisica

y los tiempos de comida en adolescentes mexicanos. Nutr

Hosp. 2015 [citado 2020 ago 12];32(3);1082–90.

Disponível em: http://www.aulamedica.es/nh/pdf/9331.pdf

- American Diabetes Association. 2: Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl1):S13-28. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S002 [Crossref]

- National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Pannel III (NCEP-ATPIII, 2001). J Manag Care Pharm. 2003;9(Suppl1):2-5. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.s1.2 [Crossref]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde.

Agência Nacional de Saúde Suplementar. Vigitel Brasil

2015 – Vigilância de fatores de risco e proteção de doenças crônicas por

inquérito telefônico. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde.; 2017. 173p.

- Jelsma D, Geuze RH, Mombarg R, Smits EBC. The impact of Wii Fit intervention on dynamic balance control in children with probable

Developmental Coordination Disorder and balance problems. Hum Mov Sci. 2014;33:404-18. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2013.12.007 [Crossref]

- Staiano AE, Abraham AA, Calvert SL. Motivating effects of cooperative exergame play for overweight and obese adolescents. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6(4):812-9. doi: 10.1177/193229681200600412 [Crossref]

- Christison AL, Evans TA, Bleess

BB, Wang H, Aldag JC, Binns

HJ. Exergaming for health:

a randomized study of community-based exergaming curriculum in pediatric

weight management. Games for Health Journal. 2016;5(6);413–21. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2015.0097 [Crossref]

- Silva MM, Carvalho RSM, Freitas MB. Bioimpedância para avaliação da composição corporal: uma proposta didático-experimental para estudantes da área da saúde. Revista Brasileira de Ensino de Física. 2019;2:e20180271. doi: 10.1590/1806-9126-RBEF-2018-0271 [Crossref]

- Staiano AE, Beyl RA, Guan W, Hendrick CA, Hsia DS, Newton RLJR. Home-based exergaming among children with overweight and obesity: a randomized clinical trial. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13(11);724-33. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12438 [Crossref]

- Kumar S, Kaufman T. Childhood obesity. Panminerva Med. 2018; 60(4);200-12. doi: 10.23736/S0031-0808.18.03557-7 [Crossref]

- Kracht CL, Joseph ED, Staiano

AE. Video Games, obesity, and children. Curr

Obes Rep. 2020;9(1):1-14. doi: 10.1007/s13679-020-00368-z [Crossref]

- Andrade A, Correia CK, Coimbra DR. The psychological effects of exergames for children and adolescents with obesity: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2019;22(11);724-35. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2019.0341 [Crossref]

- Pereira JC, Rodrigues ME,

Campos HO, Amorin PRDS. Exergames como alternativa

para o aumento do dispêndio energético: uma revisão sistemática. Revista

Brasileira de Atividade Física e Saúde. 2012;17(5):332-40. doi: 10.12820/rbafs.v.17n5p332-340 [Crossref]

- Mayer DEJ, Lawrence JM, Dabelea D, Divers J, Isom S, Dolan

L, et al. Incidence trends of

type 1 and type 2 diabetes among youths, 2002-2012. New Eng J Med.

2017;376(15):1419-29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610187 [Crossref]

- García HA, Carmona LMI, Saavedra JM, Escalante Y. Physical exercise, detraining and lipid profile in obese children: a systematic review. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2014;112(6):519-25. doi: 10.5546/aap.2014.519 [Crossref]

- Duman F, Kokacya MH, Dogru E, Katayifci N, Canbay O, Aman F. The role of active video-accompanied exercises in improvement of the obese state in children: a prospective study from Turkey. J Clin Peditr Endocrinal. 2016;8(3):334-34. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.2284 [Crossref]

- Gao Z, Chen S. Arefield-based exergames useful in preventing childhood obesity? A systematic review. Obesity Reviews. 2014;15(8):676-91. doi: 10.1111/obr.12164 [Crossref]