Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc 2021;20(4);480-89

doi: 10.33233/rbfex.v20i4.4445

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Relationship between mood state and cardiac autonomic

modulation in jiu-jitsu fighters in the pre- and post-competitive period: a

pilot study

Relação

entre estado de humor e modulação autonômica cardíaca em lutadores de jiu-jitsu

nos períodos pré- e pós-competitivo: um estudo piloto

Bruno

Nascimento-Carvalho1,2, João Eduardo Izaias¹, Ney Roberto de Jesus¹,

Adriano dos Santos1, Thália Leticia Brito

Nascimento¹, Marcio Flavio Ruaro¹, Katia Bilhar Scapini¹, Iris Callado Sanches¹

1Laboratório do Movimento Humano,

Universidade São Judas Tadeu, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

2Unidade de Hipertensão, Instituto do

Coração, Universidade de São Paulo, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil

Received:

November 13, 2020; Accepted:

August 2, 2021

Correspondence: Iris Callado Sanches, Universidade São Judas Tadeu, Rua

Taquari 546, 03166-000 São Paulo SP, Brazil

Bruno Nascimento-Carvalho: brunonascimentoc@gmail.com

João Eduardo Izaias:

joaoedi121@gmail.com

Ney Roberto de Jesus: neyoficialedf@gmail.com

Adriano dos Santos: adrianobrasco@gmail.com

Thália Leticia Brito

Nascimento: thalialeticia14@gmail.com

Marcio Flavio Ruaro:

prof.marcioruaro@gmail.com

Katia Bilhar Scapini:

katiascapini@gmail.com

Iris Callado Sanches: iris.sanches@saojudas.br

Abstract

Aim: To characterize the changes in

body composition, mood state and cardiac autonomic modulation in Brazilian

Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ) of athletes in the pre- and post-competitive periods. Methods:

Eight male athletes were evaluated in 3 moments: 14 days and 1 day before the

fight, and 2 days after the competition. Evaluations of body composition, mood

state, and cardiac autonomic modulation were performed. The repeated measures Anova test, Pearson and Spearman correlation were used for data analysis (p < 0.05). Results:

We observed reductions in anger (6.80 ± 1.69 vs. 4.20 ± 1.67 vs. 3.40 ± 1.07)

and tension (6.60 ± 0.81 vs. 5.40 ± 0.75 vs. 2.60 ± 0.88) after

competition. Vigor was reduced one day before the competition and remained the

same two days after the competition (12.80 ± 1.60 vs. 10.00 ± 1.95 vs. 10.40 ±

1.03). In addition, there was an increase in sympathetic modulation (LF-PI:

2942 ± 655.3 vs. 5479 ± 2035 vs. 5334 ± 2418 abs). There was a positive correlation

between the state of vigor and sympathetic modulation (r = 0.55), a negative

correlation between the states of depression and sympathetic modulation (r =

-0.68) and confusion and sympathetic modulation (r = -0.67). Conclusion:

These findings raised concerns about the preparation of these athletes for

competitions since changes in the state of vigor might reduce performance and

increase cardiovascular risk.

Keywords: mood state; cardiac autonomic

modulation; combat sports.

Resumo

Objetivo: Caracterizar as alterações na

composição corporal, estado de humor e modulação autonômica cardíaca em

lutadores de Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ) nos períodos pré- e

pós-competitivo. Métodos: Foram avaliados 8 lutadores em 3 momentos: 14

dias e 1 dia antes da luta, e 2 dias após a luta. Avaliou-se a composição

corporal, estado de humor e modulação autonômica cardíaca. Os dados foram

analisados por Anova de medidas repetidas e correlações de Pearson e Spearman (p < 0,05). Resultados: Estados de

humor: foi observada redução na raiva (6,80 ± 1,69 vs. 4,20 ± 1,67 vs. 3,40 ±

1,08), e tensão (6,60 ± 0,81 vs. 5,40 ± 0,75 vs. 2,60 ± 0,88) após a

competição. O vigor foi reduzido um dia antes da competição e se manteve

reduzido dois dias após a competição (12,80 ± 1,60 vs. 10,00 ± 1,95 vs. 10,40 ±

1,03). Adicionalmente, houve um aumento na modulação simpática cardíaca (BF-IP:

2942 ± 655,3 vs. 5479 ± 2035 vs. 5334 ± 2418 abs) um

dia antes da competição e se manteve aumentado no período pós-competitivo, fato

que sugere maior risco cardiovascular a longo prazo. Foi observada correlação

positiva entre o estado de vigor e a modulação simpática (r = 0,55), e

correlações negativas entre o estado de depressão e modulação simpática (r =

-0,68), e confusão e modulação simpática (r = -0,67). Conclusão: Estes

achados demonstram a necessidade de serem revistos os aspectos da preparação

competitiva destes atletas antes das competições, pois mudanças no estado de

vigor podem reduzir o desempenho e aumentar o risco cardiovascular.

Palavras-chave: estado de humor; modulação autonômica

cardíaca; esportes de combate.

Introduction

Combat sports

athletes usually go through weight loss processes since adolescence [1,2]. When

this process happens repeatedly and abruptly, it might lead to a weight gain

and loss process resulting of lower basal metabolic rate and unsuccessful

weight maintenance [3]. That may harm the athlete’s body in many ways, such as

electrolytic disturbance; cardiovascular system disorders; and mental and mood

disorders in the fighters [4,5]. These damages demonstrate the importance of

analyzing body composition of Jiu-Jitsu athletes during competition periods,

since the relationship between modifications of the athletes’ bodies, mood and

autonomic cardiovascular modulation is not too clear in the literature [6].

Studies

demonstrate the importance of checking the mood state of the athletes in the

pre-competitive period, once the high level of stress during this period may

change the psychological condition of athletes, unleashing many physical and

biomechanical adaptations in the body, which may influence competitive

performance [7,8,9,10]. Previous studies demonstrated that weight loss in the

pre-competitive period harms the mood state and increase cardiac sympathetic

modulation in combat sports athletes [5].

The heart rate

variability (HRV) is an efficient tool to estimate the risk of a cardiac

disease and measure the autonomic cardiovascular modulation, since it is an

indicator of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The ANS is responsible for

some vascular activities, such as the control of blood pressure (BP) and heart

rate (HR) [11]. The HRV shows the variations in the intervals between

consecutive heartbeats, which is related to the influence of ANS in the sinus

node, it is also a non-invasive tool that can be used as an indicator in both,

common individuals, and specific groups [12].

However, the

data are scarce of specific characteristics of jiu-jitsu fighters, as well as

their adaptations on competitive periods. This pilot study aimed to identify

the changes in body composition of jiu-jitsu fighters, their mood state and

autonomic cardiovascular modulation in the pre-competitive and post-competitive

periods.

Methods

Experimental study design

The data were

collected in the training place and was analyzed at Universidade

São Judas Tadeu. The work was developed according to

declarations and guidelines on research involving human beings: the Nuremberg

Code, Declaration of Helsinki and resolution 466/12 of

the National Health Council. The Ethics Committee approved this study in the

terms of the protocol number 1.671.569, which was provided by Universidade São Judas Tadeu. The

evaluations were carried out in three occasions: 14 days before the competition,

1 day before the competition and 2 days after the competition. These

evaluations were performed 3 times to verify the athlete's baseline status,

their pre-competition and post-competition status of mood state and

cardiovascular autonomic modulation.

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

The sample was

non-probabilistic, intentional and of convenience with 8 jiu-jitsu athletes.

The inclusion criteria were to be practicing the martial art for at least 6

months. The athletes who did not follow the preparation instructions for the

bioimpedance test were excluded.

Questionnaire of training characteristics:

All athletes

were submitted to a questionnaire to identify the features of the sample, with

questions regarding the athlete’s experience in the sport, their training

frequency, the kind, and the duration of training sessions and history of

competitions, drugs and/or anabolic steroids use.

Mood state

The BRUMS test

(BRUMS – Brunel Mood Scale) was performed on all test days. This test contains

24 simple mood indicators, such as feelings of anger, nervousness, and

dissatisfaction. The respondents answered how they felt about such situations

(the test days), according to a scale that ranged from zero (nothing) to four

(extremely). The completion of this test was performed by the individual

himself. The feelings listed on the scale constitute categories, which

correspond to the mood states of tension, depression, anger, vigor, fatigue and mental confusion [8].

Body composition

After that, we

analyzed the athlete’s body composition, their height and weight were measured

in all the occasions, and then we calculated their Body Mass Index (BMI). We

obtained additional data about body composition through the electrical

bioimpedance method using a Bioimpedance analyzer (brand: Biodynamic. Model:

BIA450). To carry out that procedure, each athlete was placed in a dorsal

decubitus position and had to be fasting for four hours before the procedure.

They were also oriented to refrain drinking alcohol, caffeine

and exercises for at least one day before the procedure. The bioimpedance test

provided the percentages of fat mass, lean body mass, and the amount of body

liquid through the passage of an electric current of low intensity (from 500 to

800 µA) and high frequency (50 kHz) through the body. The current was

imperceptible for them [5].

Hemodynamic data

After those

procedures, blood pressure was measured using a digital measurer (brand: OMRON

model: HEM-705CPIN), three times (with an interval of 2 minutes between each

measurement), as directed by the Brazilian Society of Hypertension (2010). The

athlete’s heart rate was recorded for 25 minutes when they were at rest (to

analyze the autonomic cardiovascular modulation subsequently) [5].

Heart rate variability

RR

intervals (IP2ms) were recorded using a heart rate monitor (brand:

Polar®, model: S810). The transmitter, which is clipped to a belt, detect the

electrocardiographic signal from heartbeat to heartbeat and transmit it through

an electromagnetic wave to a Polar® receiver clipped to the wrist, where the

information is digitalized, displayed and archived

[12]. This system can detect the ventricular depolarization, which corresponds

to the R wave in the electrocardiogram, with a 500 Hz Electrocardiogram

sampling frequency and a 1ms temporal resolution [13].

After the

cardiac signal was recorded, the data was transferred to the Polar Precision

Performance Software ® using the Infrared Interface (IrDA). That software

enables bidirectional data exchange with a microcomputer for later analysis of

cardiac pulse interval variability (RR) in different situation. After these

procedures, the data was transferred and saved to Text files, using Kubius software to analyze heart rate variability in both

time domain and frequency domain (Rapid Transformation) [5].

Regarding the

analysis of the autonomic cardiovascular modulation in the frequency domain,

the following parameters were observed: the low-frequency band (LF-PI,

sympathetic modulation), high frequency band (HF-PI, parasympathetic

modulation) and the ratio between low-frequency band and high-frequency (LF/HF

balance) [12].

Statistical analysis

Data were

presented as mean ± standard deviation. Homogeneity of the data was tested

using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The difference between the three moments was

verified using the repeated measures ANOVA test. Spearman and Pearson

correlations were also used. Significance was set to p < 0.05.

Results

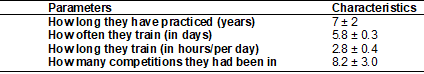

The participants

were 27.6 ± 2.42 years old. The data regarding how long they had practiced the

sport, how often they participated in competitions in the last months, how

often they trained and the kind of training they had are reported in Table I.

The participants did not use weight loss strategies for competitions while

tests were carried out, according to them. Nonetheless, three participants

reported to have used diuretic medicines in past competitions to lose weight in

the pre-competitive period. One participant told us that he had used an

anabolic steroid (Deposteron) to maximize his

performance 2 years ago.

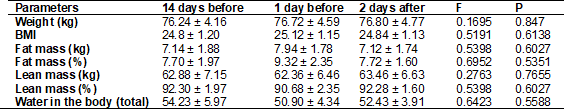

Regarding the

specificity of their training, it was reported that they had, on average, 132 ±

34.99 minutes of technical training, 42 ± 7.34 minutes of physical training in

every weekly training session. We did not find any relevant changes in the

following parameters: body weight, BMI, lean body mass, fat body mass and total

amount of water in the body (Table II).

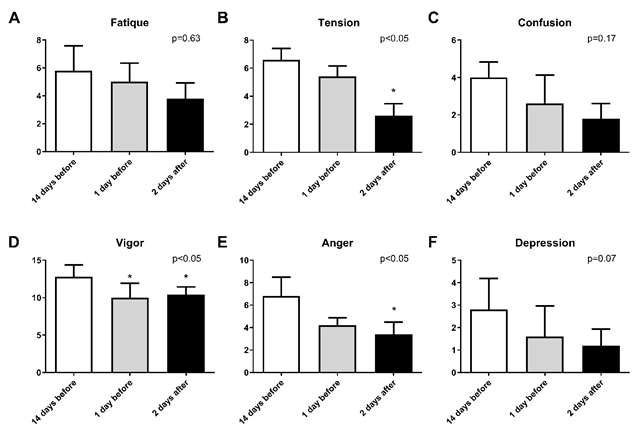

The values

obtained using the Brums scale did not indicate any changes in fatigue (Figure

1A), neither in mental confusion (Figure 1C), nor in depression (Figure 1F) in

none of the 3 evaluations conducted in the pre-competitive and post-competitive

periods. However, we found some decrease in tension (Figure 1B) (14 days

before: 6.60 ± 0.81; 1 day before: 5.40 ± 0.75; 2 days after: 2.60 ± 0.87),

vigor (Figure 1D) (14 days before: 12.80 ± 1.59; 1 day before: 10.00 ± 1.94; 2

days after: 10.40 ± 1.03) and anger (Figure 1E) (14 days before: 6.80 ± 1.69; 1

day before: 4.20 ± 0.66; 2 days after: 3.40 ± 1.08) values obtained in the test

carried out post fight when compared to baseline.

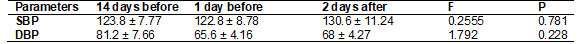

No statistical

difference was found in the values regarding the arterial pressure, neither the

systolic or in the diastolic (Table III). Results

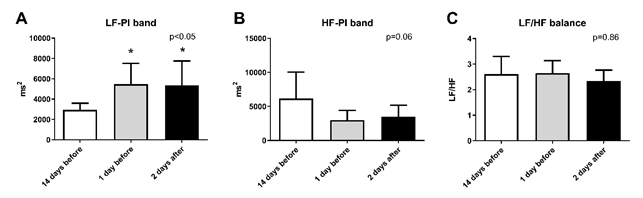

showed an increase in cardiac sympathetic modulation (LF-PI band) (14 days

before: 2942 ± 655.3; 1 day before: 5479 ± 2035; 2 days after: 5334 ± 2418 ms2)

evaluation before the competition and in post-competitive period when compared

to baseline evaluations, suggesting an increase in the possibility of high-risk

cardiovascular disorder in the athletes (Figure 2A). We did not find any

changes in the parasympathetic modulation (HF-PI band) (Figure 2B), neither in

the sympatho-vagal modulation (LF/HF) (Figure 2C).

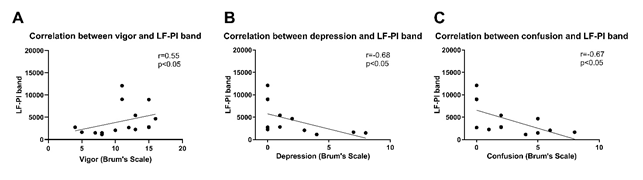

No significant

correlation was observed between all parameters of mood states and sympatho-vagal modulation (LF/HF). States of tension (r =

0.11 p =0.71), anger (r = -0.44 p = 0.14), fatigue (r = 0.53 p = 0.19), vigor

(r =- 0.21 p = 0.47), depression (r = 0.42 p = 0.15), confusion (r = 0.07, p =

0.82) and sympatho-vagal modulation. Moreover,

correlation analyzes were performed between mood states and cardiac sympathetic

modulation (LF-PI band). No significant correlation was observed between mood

states tension (r = -0.40 p = 0.17), anger (r = 0.29 p = 0.33), and fatigue (r

=- 0.02 p = 0.93) and sympathetic modulation. However, a positive correlation

was observed between vigor and sympathetic modulation (r = 0.55 p < 0.05)

(Figure 3A), negative correlations between depression and sympathetic

modulation (r =- 0.68 p < 0.05) (Figure 3B) and between confusion and

sympathetic modulation (r =- 0.67 p < 0.05) (Figure 3C).

Table I - Characteristics

of the athletes who participated in this study

The data are presented

with mean ± standard deviation

Table II - Distribution

and body composition of the athletes

kg = kilograms. The

data are presented with mean ± standard deviation.

Table III - Parameters

related to the arterial pressure

SBP = Systolic blood

pressure; DBP = diastolic blood pressure. The data are presented with mean ±

standard deviation

Figure 1 - The

affect conditions according to the Brums Mood Scale 14 days before the fight,

one day before the fight and two days after the fight. (A)

Fatigue, (B) Tension, (C) Confusion, (D) Vigor, (E) Anger, (F) Depression. * p

< 0.05 vs. 14 days before the fight. Repeated measures ANOVA test

Figure 2 - Cardiac

autonomic modulation 14 days before the fight, one day before the fight and two

days after the fight. (A) Low-frequency band of the R.R. intervals (B)

High-Frequency Ban of the R.R. Intervals. (C) Sympatho-vagal

balance. *p < 0.05 vs. 14 days before the fight. Repeated measures ANOVA

test

Figure 3 - Correlation

between (A) Vigor and low-frequency of pulse interval band, (B) Depression and

the low-frequency of pulse interval band and (C) Mental confusion and

low-frequency of pulse interval band. Spearman correlation test

Discussion

This study

presented previously unpublished results on the changes in the mood state and

the cardiac autonomic modulation of jiu-jitsu fighters in the pre-competitive

and post-competitive period. Despite the small sample can be a limiting factor

of this study, the athletes are experienced, considering the many years they

had been practicing and the number of competitions they had participated.

Usually, the

mood condition is related to the “optimism” construct, which can influence

athlete’s self-confidence during competitions and lead to a better performance

and better outcomes [8,14,15]. The fighters have a higher percentile regarding

vigor when compared to other states in the three evaluated moments in the

pre-competitive period, which was also found regarding other sports [8]. This

condition, in which the values related to vigor are higher and the values

related to the other feelings (fatigue, mental confusion, depression, anger and

tension) are lower is known as “Iceberg Profile” and shows a positive mental

condition of the athletes [16].

Nonetheless, the

decrease in vigor as the competition day (1 day before the fight vs. 14 days

before the fight) approaches is worrisome, since this should be when the

athletes are at the peak of the technical, physical, and psychological

preparation, compared to all the previous moments. This demonstrates that some

aspects of their training should be reviewed. Regarding the reduction in the

feelings of tension and anger in the post-competitive period (2 days after the

fight vs. 14 days before the fight), that is exactly what we expected, once the

training period and competitive period was over in that moment.

No change was

found in feelings of fatigue, depression, and mental confusion. The stability

of the percentiles related to the feeling of fatigue is an important predictor

of the athlete’s performance during the competition, according to a study that

analyzed the performance of two-year training of judo fighters for the 1992

Olympic Games [7].

A relevant

aspect of those athletes physical training is the amount of time devoted to

technical training, rather than to physical training. That fact indicates that,

in general, fighters use the biological principle related to the specific

characteristics of the sport (principle of specificity), by which their body is

provided with specific stimuli that are useful to the practice of the sport.

This promotes a better adaptation to the demands of the body during

competitions, especially in the muscular system, motor system, and body

joints [17]. Another study published shows similar results to those found

in our study with fighters of different combat sports [5].

The fighters

reported not to use any strategy to lose weight quickly in the pre-competitive

period. However, 37.5% of them reported they had done it in the past. It is

important to point out that a quick weight loss process harms the body in many

ways, such as causing hormonal imbalance, electrolytic disturbance, mood

disorders, disorders in the cardiovascular system and a decrease in physical

strength [3]. The results regarding the body composition of the athletes have

confirmed that there were no changes in the parameters related to that neither

in the pre-competitive nor in the post-competitive period.

Jiu-jitsu is

considered a good physical conditioning strategy for healthy individuals

regarding the cardiovascular system, since its recovery period after exercises

promotes blood pressure and heart rate decrease [18]. Indeed, the systolic and

diastolic blood pressure values are maintained in the present study, regardless

of the stress generated by the pre-competitive preparation process. However,

there was an increase of 16 mmHg in diastolic arterial pressure (14 days before

of fight vs. 1 day before of fight) and increase of 8 mmHg in systolic arterial

pressure (1 day before of fight vs. 2 days after of fight), that are clinically

relevant. It might be explained by fluctuations in the autonomous control that

regulates hemodynamic parameters [19].

The cardiac

autonomic modulation is an important and non-invasive analysis that provides

indicators for sympathetic and parasympathetic autonomic modulation. These two

complex systems are essential to keep the organic balance [19]. Reflexive

responses of the sympathetic and the parasympathetic systems allow adjustments

of cardiac output and vascular peripheral resistance, contributing to the

stabilization and maintenance of systemic blood pressure during different

physiological situations [20]. The high values of cardiac sympathetic

pre-combat evaluation (1 day before of fight vs. 2 days after of fight), and

the remaining high values in the post-combat analysis can be considered

worrisome. Considering previous studies that demonstrated that a higher of

cardiac sympathetic modulation is a strong indicator of increased risk of

cardiovascular diseases, since it presents less capacity for adaptation in

stressful situations in different populations [20,21].

We found

interesting that the values regarding mental confusion and depression remained

stable, regardless of whether the test was conducted in the pre-competitive or

in the post-competitive period. However, they are negatively related to cardiac

sympathetic modulation. The correlation between the feeling of vigor and the

cardiac autonomic modulation during a competition is described in a study with

Paralympic athletes during a competition. In that study, the authors found a

positive correlation between the indicators of cardiac parasympathetic

modulation and vigor [8].

Nonetheless, we

found a positive correlation between vigor and the cardiac sympathetic

modulation. An important fact to point out is that the cardiac autonomic

modulation is controlled by both the sympathetic and parasympathetic functions

in an integrated way, because of that, we can consider that the capacity of

vigor to affect the sympathetic autonomic function is natural. Another

important factor is the changes in values of cardiac sympathetic modulation and

vigor from the second test (one day before the fight) and from the third test

(two days after the fight) which are similar.

Conclusion

The main results

of this study demonstrate remarkable changes in the mood state and in the

cardiac autonomic modulation in jiu-jitsu fighters in the pre-competitive and

post-competitive periods. These findings highlight the need to review some

aspects of the training strategies of the athletes before competitions, because

the decrease found in vigor may interfere with their performance and induce

imbalances on cardiac autonomic modulation.

Potential conflict of

interest

No conflicts of

interest have been reported for this article.

Financing source

This study was financed

in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES)

- Finance Code 001.

Author’s contributions

Conception and design

of study: Nascimento-Carvalho B, Sanches IC, Izaias JE; Acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation of

data: Nascimento-Carvalho B, Sanches IC, Izaias JE, de Jesus NR, Nascimento TLB; Drafting the

manuscript: Nascimento-Carvalho B, Sanches IC, Izaias JE; Revising the manuscript critically for important

intellectual content: Nascimento-Carvalho B, Sanches

IC, Ruaro MR, Scapini KB.

References

- Lorenço-Lima

L De, Hirabara S. Efeitos da

perda rápida de peso em atletas de combate. Rev Bras Ciências do Esporte 2013;35:245-60. doi: 10.1590/S0101-32892013000100018 [Crossref]

- Castor-Praga C, Lopez-Walle JM, Sanchez-Lopez J. Multilevel evaluation of rapid weight loss in wrestling and taekwondo. Front Sociol 2021;6:1-14. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.637671 [Crossref]

- Artioli GG, Franchini E, Junior AHL. Weight loss in grappling combat sports: Review and applied recomendations. Rev Bras Cineantropometria Desempenho Hum 2006;8:92-101. doi: 10.1590/%25x [Crossref]

- Silva

JMLO, Gagliardo LC. Análise sobre os métodos e

estratégias de perda de peso em atletas de mixed martial arts em período pré-competitivo. Rev Bras Nutr Esportiva 2014;8:74-80.

- Nascimento-Carvalho B, Mayta MAC, Izaias JE, Doro MR, Scapini K, Caperuto E et al. Cardiac sympathetic modulation increase after weight loss in combat sports athletes. Rev Bras Med Esporte 2018;23:413-7. doi: 10.1590/1517-869220182406182057 [Crossref]

- Andreato LV, Franchini E, Moraes SMF, Esteves JVC, Pastório JJ, Andreato TV, et al. Morphological profile of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu elite athletes. Rev Bras Med Esporte 2012;18:46-50. doi: 10.1590/S1517-86922012000100010 [Crossref]

- Gabilondo

JA, Arrieta M, Balagué G. Rendimiento deportivo e influencia del estado de ánimo, de la dificultad

estimada, y de la autoeficacia

en la alta competición. Rev Psicol del Deport

1998;7:0193-204.

- Santos Leite G, Amaral DP, Oliveira RS, Oliveira Filho CW, Mello MT, Brandão MRF. Relação entre estados de humor, variabilidade da frequência cardíaca e creatina quinase de para-atletas brasileiros. Rev da Educ Fis 2013;24:33-40. doi: 10.4025/reveducfis.v24.1.17021 [Crossref]

- Lazarus RS. How emotions influence performance in competitive sport. Sport Psychol 2000;14:229–52. doi: 10.1123/tsp.14.3.229 [Crossref]

- Rocha

CA. Humor e estresse de judocas em treinamento e competição [Dissertação].

Florianópolis: Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina; 2010.

- Mangueira LB, Benjamim CJR, Silva JRA, Alcantara GC, Monteiro LRL, Moraes YM, et al. Influência da atividade física na modulação autonômica cardíaca. Rev e-ciência 2018;6:65-71. doi: 10.19095/rec.v6i1.414 [Crossref]

- Vanderlei M, Pastre CM, Hoshi A, Dias T, Fernandes M. Noções básicas de variabilidade da frequência cardíaca e sua aplicabilidade clínica. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc 2009;24:205–17. doi: 10.1590/S0102-76382009000200018 [Crossref]

- Loimaala A, Sievänen H, Laukkanen R, Pärkkä J, Vuori I, Huikuri H. Accuracy of a novel real-time microprocessor QRS detector for heart rate variability assessment. Clin Physiol 1999;19:84–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.1999.00152.x [Crossref]

- Gil RB, Montero FO, Fayos EJG, Lòpez Gullòn JM, Pinto A. Otimismo, burnout e estados de humor em desportos de competição. Anal Psicol 2015;33:221-33. doi: 10.14417/ap.1019 [Crossref]

- Ricardo

de la Vega, Álvaro Galán, Roberto Ruiz CMT. Estado de

ánimo precompetitivo y rendimiento percibido en Boccia Paralímpica. Revista de Psicologia del Deporte [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2021 Aug 2];22:39-45. Available from:

https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2351/235127552006.pdf

- Raglin JS.

Psychological factors in sport performance: the mental health model revisited. Sport Med 2001;31:875. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200131120-00004 [Crossref]

- Bompa

O. Periodização: teoria e metodologia do treinamento. São Paulo: Phorte; 2002. p. 440.

- Prado EJ, Lopes MCA. Resposta aguda da frequência cardíaca e da pressão arterial em esportes de luta (Jiu Jitsu). Rev Atenção à Saúde 2010;7:63–7. doi: 10.13037/RBCS.VOL7N22.523 [Crossref]

- Irigoyen

MC, Consolim-colombo FM, Krieger EM. Controle

cardiovascular: regulação reflexa e papel do sistema nervoso simpático. Rev Bras Hipertens

2001;8:55-62.

- De

Angelis K, Santos MSB, Irigoyen MC. Sistema nervoso

autônomo e doença cardiovascular. Rev Soc Cardiol do Rio Gd do Sul [Internet]. 2004 [cited

2021 Aug 2];13:1-7. Available

from: http://sociedades.cardiol.br/sbc-rs/revista/2004/03/artigo02.pdf

- Francica JV, Heeren M V., Tubaldini M, Sartori M, Mostarda C, Araujo RC, et al. Impairment on cardiovascular and autonomic adjustments to maximal isometric exercise tests in offspring of hypertensive parents. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2013;20:480-5. doi: 10.1177/2047487312452502 [Crossref]