Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc 2021;20(3):398-412

doi: 10.33233/rbfex.v20i3.4562

REVIEW

Exercise-induced or exacerbated immune and allergic

syndromes: what the exercise health professional needs to know about immunoallergic diseases and sport?

Síndromes

imunológicas e alérgicas induzidas ou exacerbadas por exercício: o que o

profissional de saúde do exercício precisa saber sobre doenças imunoalérgicas e esporte?

Sérgio

Dortas Duarte Júnior1, Guilherme Gomes

Azizi1

1Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro,

Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

Received:

January 21, 2021; Accepted:

June 21, 2021.

Correspondence: Guilherme Gomes Azizi, Rua

Prof. Rodolpho Paulo Rocco, 255, 9°andar, Sala 9E10, Cidade Universitária da

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 21941-617 Rio de Janeiro RJ, Brazil

Sérgio Dortas Duarte Júnior:

sdortasjr@gmail.com

Guilherme Gomes Azizi:

gazizi247@gmail.com

Abstract

Exercise-induced or exacerbated immunoallergic

diseases are significantly important situations for both amateur and professional

athletes. Asthma, bronchospasm, exercise-induced laryngospasm

and anaphylaxis, chronic inducible urticaria, and hereditary angioedema are

examples of these situations. This article aims to contribute to the knowledge

of health professionals with guidance on the diagnosis and management of

hypersensitivity disorders induced by exercise or triggered during sports

practice, to allow their patients to safely perform activities related to

exercise.

Keywords: asthma; anaphylaxis; angioedema; exercise;

urticaria

Resumo

As

doenças imunoalérgicas induzidas ou exacerbadas pelo

exercício são situações significativamente importantes tanto para atletas

amadores quanto profissionais. Asma, broncoespasmo, laringoespasmo

e anafilaxia induzidos pelo exercício, urticárias crônicas induzidas e

angioedema hereditário são exemplos destas situações. O objetivo deste artigo é

contribuir para o conhecimento de profissionais de saúde com orientação ao

manejo de distúrbios de hipersensibilidade induzidos por exercícios ou desencadeados

durante a prática esportiva, para permitir que seus pacientes realizem, com

segurança, as atividades relacionadas ao exercício.

Palavras-chave: asma; anafilaxia; angioedema;

exercício; urticária

Exercise-induced

or exacerbated immune allergic diseases are significantly important situations

for both amateur and professional athletes. Asthma, bronchospasm,

exercise-induced laryngospasm and anaphylaxis,

inducible urticaria, and hereditary angioedema are examples of these

situations. This article aims to contribute to the knowledge of health

professionals with guidance on the diagnosis and management of hypersensitivity

disorders induced by exercise or triggered during sports practice, to allow

their patients to safely perform activities related to exercise.

Exercise-induced asthma/bronchospasm

Exercise-Induced

Bronchospasm (EIB), formerly called “Exercise-Induced Asthma”, is defined as

the transient narrowing of the airways in response to a wide variety of

bronchoconstrictor stimuli related to intense physical exercise, presenting

symptoms such as coughing, dyspnea, and wheezing. This condition occurs in a

subgroup of individuals with asthma and in some non-asthmatics [1,2,3]. Thus,

demonstrating a characteristic of intense airway hyperresponsiveness, EIB is

more common in winter sports athletes and swimmers than in general population

and athletes from other sports.

The prevalence

in the Brazilian population was analyzed in 2 studies from different regions, Recife and São Paulo. Both demonstrated that children and

adolescents with asthma have a prevalence of about 45% of EIB [4,5].

The intensity of

ventilation, a fundamental factor for adequate oxygen supply during physical

activity, can also be the "Achilles tendon"

in individuals subject to EIB, as we can go from 6 L/min of respiratory volume

to more than 200 L/min. In addition, breathing becomes progressively oral, from

the moment the individual reaches 30 L/min.

Thus, mouth

breathing does not have the range of mechanisms present during adequate nasal

breathing, in which there is humidification and air heating, in addition, with

greater flow, there is greater exposure to aeroallergens, irritants to the

mucosa and particulate matter, which in the long term, can participate in the

pathophysiology of respiratory diseases such as asthma and mixed rhinitis

[6,7].

The

pathophysiology of EIB is not yet fully described, however, studies indicate

that there is possibly a correlation between airway cooling through inhaled air

and subsequent rewarming of the airways after exercise [8]. Another proposed

hypothesis is related to airway dehydration air, which through the intensity of

ventilation, results in an increase in the osmolarity of the local fluid,

increasing the periciliary movement and, consequently, increasing the water in

the bronchial lumen [9]. Thus, it would release inflammatory mediators leading

to bronchoconstriction through the contraction of smooth and edema [10].

Exercise immunology could explain the third hypothesis for this multivariate

pathology, since high-performance athletes go through periods of transient

immunosuppression called “Open Window”, in which they are more susceptible,

especially which can exacerbate symptoms pre-existing conditions or cause

isolated bronchoconstriction [11,12,13].

The diagnosis of

asthma can be made based on a history of characteristic symptoms (cough,

wheezing, chest pain, and dyspnea) and documentation of variable airflow

limitation, by means of spirometry with bronchodilator testing or

bronchoprovocation tests, as the clinical diagnosis in the EIB can be

complicated [14]. The diagnosis of EIB uses the variation in FEV1 before and in

sequences of 5, 10, 15, and 30 minutes after the provocation tests, through

vehicles such as treadmills or stationary bicycles. Forced expiration maneuvers

should be performed in a standardized way, and the calculation of the variation

should be performed in relation to the baseline value, with a reduction in FEV1

> 10% or 15%, which are observed in one or two moments of the assessment,

depending on the literature [14]. To carry out the provocation test, the

athlete should not practice any exercise in the previous 4 hours, as this could

lead to a false-negative result, due to refractoriness in this period [1,16].

Differential

diagnoses to EIB must always be considered, such as exercise-induced

laryngospasm, poorly controlled rhinitis, gastroesophageal reflux, and

hyperventilation syndrome. The goals of asthma treatment are to achieve and

maintain asthma control, improve lung function, and prevent risk factors for

acute events such as exacerbations. Specifically, in relation to the EIB, it

will directly depend on the correlation with asthma or not [17,18].

Environmental

measures and masks can help reduce the effects of exposure to cold air on

winter sports athletes or the inhalation of air pollutant particles [19].

In addition to

these, the pre-exercise warm-up can result in a reduction in

bronchoconstriction by exercise in about 50% of individuals, which is performed

for at least 10 to 15 minutes, reaching up to 60% of the maximum heart rate.

Then, the athlete will enter a "refractory period" induced by the release

of protective prostaglandins [20].

There are few

randomized clinical trials for an adequate analysis of pharmacotherapy for the

treatment of EIB. However, inhaled glucocorticoids are the mainstay of therapy

for asthma, as this is basically a pathology with inflammatory characteristics

[16], these agents, by inhalation, are allowed by sports authorities, such as

the World Anti-doping Agency (WADA) and the Authority Brazilian Association of

Doping Control (ABCD) [22,23].

The most

commonly used strategy for athletes with or without asthma and who have EIB is

treatment with inhaled glucocorticoids, inhaled b2-agonists before exercise (regular or if necessary)

in association or not with b2

receptor antagonists leukotrienes (montelukast)

[1,23].

Long-acting b-agonists are good options for athletes, as they have

a bronchodilator action of up to 12 hours, unlike salbutamol, the main

short-acting b-agonist

with an action of up to 3 hours [18]. Formoterol and salmeterol (b-agonists of long-lasting) have no WADA restriction.

The association with inhaled corticosteroids is increasingly present, leaving

the isolated prescription of b-agonists

in the past, as this interaction minimizes tachyphylaxis and favors

inflammation control [17].

Immunotherapy

for aeroallergens has limited effectiveness in direct relation to EIB, as there

are no large studies, however, immunotherapy is widely used in asthma or

allergic origin, so this possibility should be analyzed together with the

specialist, as in addition to being a modifying factor in the natural history

of the disease, it is not a treatment characterized as doping [17,21,24].

Thus, we must

emphasize that the health professional must act both for the health of the

individual and for the well-being of the individual's work instrument, their

body, since any reduction in physical capacity can be the line between victory

and defeat.

Exercise-induced laryngospasm

Exercise-induced

laryngospasm (EILs) are a group of conditions that cause laryngeal obstruction

during exercise, among these are exercise-induced laryngomalacia (EIL, a

supraglottic obstruction caused by arytenoid collapse) and exercise-induced

vocal cord dysfunction (CVIE) [25,26].

EILs have

symptoms like exercise-induced asthma and have a high prevalence among the

population, however, it is still confused with EIA, which causes a

misdiagnosis, however, many do not have associated asthma [27,28] from

approximately 5% to 7% among adolescents and young adults [29].

The supraglottic

obstruction appears to precede the inspiratory glottic narrowing, in greater

proportion than during the expiratory period [20]. This and other

anatomical-physiological factors provide some hypotheses that suggest that EIL

has varied etiologies, these being the size of the larynx, which could

contribute as a causal or facilitating factor, such as during puberty, when the

laryngeal diameter of women begins its process of reaching a smaller diameter

in relation to men, explaining the higher prevalence of adolescent women with a

report of EIL [30,31].

Another

etiological hypothesis involves the pressure difference during the increase in

intensity in a physical activity that normally requires accelerated breathing

movements. Thus, it would be a partially passive phenomenon, in which increased

effort and ventilation would increase the negative transmural pressure [32].

In addition, the

anterior movement of the epiglottis puts tension on adjacent structures and

would facilitate supraglottic closure, mainly due to the high tension of the

aryepiglottic fold, pulling the arytenoid mucosa anteriorly, reducing the

circumference of the larynx [33].

A third

hypothesis would be hypersensitivity of the upper airways, in a physiological

reflex of the glottic region to avoid aspiration, which could explain an

inadequate local adduction [33].

In addition to

these hypotheses, a fourth possibility was proposed for the origin of symptoms,

which would be closely related to gastroesophageal reflux, as after acid reflux

reaching the laryngopharyngeal area, it would induce a state of

hyperexcitability [34]. Thus, complementary diagnostic research is indicated

and propose treatment with proton pump inhibitors. We must remember that the

prevalence of reflux in the population varies between 10% and 60% [35].

Therefore, this would be a reasonably important hypothesis to be considered.

The management

of the EIL is still under wide discussion and without a defined consensus,

mainly due to the heterogeneity of the etiology and the possible phenotypes

involved. Thus, a careful evaluation is indicated, in which predisposing and

irritating factors that may develop the obstruction are excluded, in addition

to the exclusion of differential diagnoses, including exercise-induced

bronchospasm. Studies also associate psychological therapy as a complementary

factor in treatment [36,37].

Some reports

sought to identify possible therapies such as the use of inhaled ipratropium

bromide before the activity, which would reduce vocal cord dysfunction [38]. In

addition to the approaches described above, the possible surgical intervention

should be evaluated together with the otolaryngologist surgeon.

Exercise-induced anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis is

derived from the Greek language ana ("inversion", "repeat")

and phylaxis ("guard", "immunity"), having been adopted by

Charles Robert Richet and Paul Portier in 1902 [38]. It is characterized by an

intense and potentially hypersensitivity reaction fatal that results from a

systemic release of inflammatory mast cell and basophilic mediators such as

histamine, leukotrienes, tryptase, often correlated with a reaction involving

immunoglobulin E (IgE) [38,39].

Anaphylactic

reactions have an intense correlation with some allergens common in our

environments, such as food, anti-inflammatory drugs, b-lactams, and insect venom (bees and wasps), due to

previous sensitization (specific IgE) [40]. However,

there are anaphylactic conditions in which the patient does not have

sensitization to the causative agent, as indirect mast cell degranulation after

MRGPRX2 receptor stimulation by drugs (quinolones, neuromuscular blockers, icatibant, opioids), mastoparan

wasp venom, and substance P [41,42].

The clinical

characterization of anaphylaxis is still not consensual. The clinical picture

starts about 5-30 minutes after exposure to the allergen, however, symptoms can

be observed within 6 hours.

Manifestations

generally occur with skin involvement associated with one or more of the

respiratory (70%), cardiovascular (10-45%), central nervous system (10-15%),

and gastrointestinal tract (30-45%) systems. However, possible anaphylaxis

should not be neglected if there is no skin involvement [42,43].

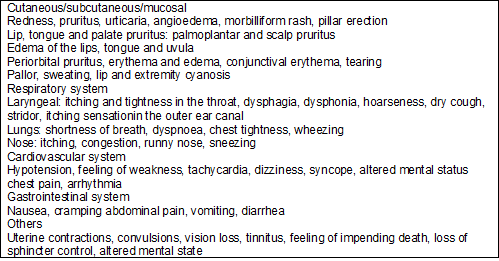

Chart I - Signs and

symptoms

Modified of

“Guia para manejo da anafilaxia-2012” – Grupo de Anafilaxia da ASBAI. Rev Bras Alerg Imunopatol

2012;35(2)

The differential

diagnosis of anaphylaxis must be considered, however, disregarding possible

anaphylaxis can lead to the patient's death. Thus, any affection that acts on

the skin and mucous membranes can cause laryngotracheitis, bronchial

obstruction, or an asthma exacerbation, as well as vasovagal syncope, pulmonary

embolism, and other emergencies in other systems correlated with anaphylaxis

[42].

Exercise-induced

anaphylaxis (EIA) is a condition initially reported by Maulitz

et al. [44] in 1979, which described a picture of hypersensitivity

occurring in vigorous physical activity preceded by ingestion of shellfish

(shrimp and oysters) between 5 and 24 hours before.

It is estimated

that EIA may have an incidence between 7 and 9% within the epidemiology of

anaphylaxis [45], and may occur at any intensity of physical activity, however,

studies have shown that sports with lower cardiovascular demand have fewer

reports [46].

Foods with the

greatest involvement in exercise-induced anaphylaxis with IgE-mediated

food dependence are wheat (correlated with 5-omega-gliadin), shellfish,

peanuts, corn, cow's milk, soy, mite-contaminated flours, and fruits from

Rosaceae family (peach, loquat, plum, apricot, cherry, and others) [44,47]. The

symptoms can start during or after exercise, however, most occur about 30

minutes after stopping the activity [44].

EIA may also

have medications as triggers, mainly non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics (cephalosporins), requiring the

interaction between medication and physical activity [44].

Several

hypotheses have been suggested to explain this disease. The most accepted

hypothesis would be the correlation of physical activity with increased

gastrointestinal permeability [44]. This pathophysiology would be related to

the increase in low-affinity IgE receptors in the

intestinal mucosa cells, which, in patients with food allergy, could stimulate

the cascade inflammatory potentiated by increased blood flow to physical

exercise. Studies have shown that exercise and ASA enhance the absorption of

allergens, especially the omega-5-gliadin present in wheat. Thus, if a food

challenge with exercise or AAS occurs or is purposely performed, it could

induce the anaphylactic manifestation [44,47].

Transglutaminase

could alter the absorption of food allergens, which in association with

exercise could accelerate the process of allergen distribution. Other triggers

described in the literature would be environments of high or low temperature,

high humidity, exposure to seasonal pollen, especially in northern hemisphere

countries, alcoholic beverages, stress, infection, and menstrual period [48].

The diagnosis is

entirely related to a good anamnesis. However, serum tryptase measurement after

the suspected or confirmed condition of exercise-induced anaphylaxis could

confirm this, as well as in anaphylaxis, enabling subsequent preventive

intervention regarding the allergen triggering the reaction. Thus, the

investigation of allergic sensitization to foods. However, if the history and

the search for sensitization (specific IgE) are not

clear, the challenge test will be an important tool.

There is no

standardized challenge test exclusively for EIA. However, the Bruce protocol is

a maximal exercise test that uses a treadmill and encourages an increase in

speed and incline every 3 minutes, so, due to its easy reproduction, this test

is widely used in association with the previous intake of said food causing the

reaction. We must remember that the environment must be controlled, vital signs

must be monitored continuously and the test must be

performed under medical supervision. The patient should be asked to discontinue

antihistamines and leukotriene antagonists for at least 3 days before the

challenge test [49,50,51].

After the

diagnostic hypothesis is proposed, the necessary support must be offered for

the well-being of the athlete or practitioner of physical activity. All

patients should be prescribed and trained to manage self-injecting epinephrine.

In addition, the patient must be educated about the characteristic symptoms of

anaphylaxis, its possible triggers (avoid food between 4-6h prior to exercise,

avoid aspirin and/or NSAIDs between 24 and 48h prior to activity) involved in

each case, and recommends the performance of physical activities always

accompanied. H1 antihistamines can and should be used according to the

symptoms, on a regular basis or before physical activity, if the specialist

deems it necessary [41,44].

Chronic inducible urticaria

According to

current guidelines, urticaria is defined as a condition determined by the onset

of urticaria, angioedema, or both. Wheals is characterized by a lesion with

central edema of variable size, almost always surrounded by erythema, a

sensation of itching or burning, and fleeting nature, with the skin returning

to its normal appearance between 30 minutes and 24 hours. Angioedema, in turn,

presents as sudden and pronounced edema of the lower dermis and subcutaneous

tissue, or mucous membranes, with a sensation of pain at the site, and slower

resolution than wheals, which may last up to 72 hours [52].

Urticaria is

classified according to the duration of clinical manifestations as acute when

signs and symptoms persist for less than 6 weeks, or chronic in cases where it

manifests daily or almost daily for 6 or more weeks. Chronic urticaria (UC), in

turn, can occur spontaneously or be induced by specific stimuli such as cold,

heat, pressure, increase in body temperature (cholinergic urticaria), etc.

[52].

Cholinergic

urticaria and cold urticaria are important situations to be considered in the

context of sports practice [53]. Cholinergic urticaria is characterized by the

appearance of micropapular lesions, related to an

increase in body temperature, from physical exercise or local application of heat; in addition to emotional stress, spicy foods or hot

drinks. The lesions are approximately between 1 and 3 mm, located on the trunk

and upper limbs. Lesions tend to last 15 to 60 minutes and may be associated

with local angioedema. If cholinergic urticaria is suspected, it is important

to differentiate it from exercise-induced anaphylaxis, aquagenic urticaria,

adrenergic urticaria, and cold-induced cholinergic urticarial [54,55].

The provocation

test to confirm cholinergic urticaria also aims to rule out exercise-induced

anaphylaxis. A standardized protocol for diagnosing and measuring cholinergic

urticaria thresholds using heart rate monitoring exercise testing has been

proposed. The test is performed by ergometry with heart rate control, so the

patient positions himself on the ergometric bicycle and starts pedaling, being

instructed so that the heart rate rises by 15 beats per minute every 5 minutes,

reaching 90 beats per minute above the basal level after 30 minutes. The time for

the onset of urticaria is inversely proportional to the intensity of the

disease (image 1), that is, the shorter the time for the onset of lesions, the

more severe the cholinergic urticaria is [54].

Image 1 - Lesions

compatible with cholinergic urticaria after provocation test. HUCFF-UFRJ Immunology Service

Courtesy

The therapy of

the first choice consists of non-sedating antihistamines. However, there are

alternatives for refractory cases such as omalizumab, an anti-IgE monoclonal antibody.

Cold urticaria

is defined by the appearance of wheals after exposure to cold, whether by solid

objects, air, or cold liquids. Lesions are usually limited to the site of

contact with cold (wheals and angioedema), but they can be generalized and

accompanied by systemic manifestations, including progression to acute

respiratory failure and anaphylaxis. These mainly occur in situations such as

carrying refrigerated objects, swimming in ice water, staying, or entering a

refrigerated environment, which can put swimmers and skiers at high risk

[52,56].

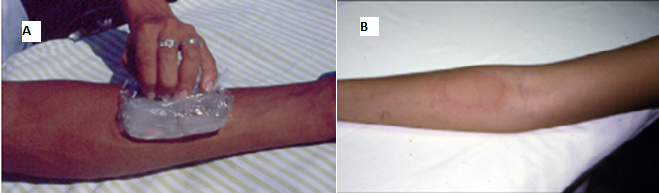

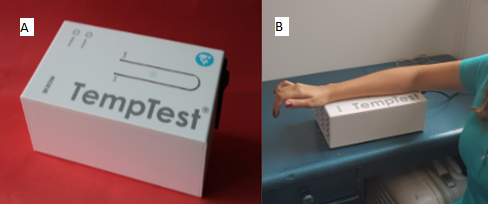

Challenge

methods for cold urticaria include the classic “ice cube test” (picture 2 and

2.1) and the TempTest® (picture 3 and 3.1). Management of cold urticaria includes: avoiding cold exposure, drinking or cold

foods; non-sedating antihistamines in recommended doses or even quadrupled; in

selected cases the use of omalizumab. In severe cases, with cold anaphylaxis,

an emergency plan must be instituted, including the prescription of epinephrine

autoinjectors, which is the gold standard medication in severe conditions

involving inflammatory mediators, such as histamine [54].

Image 2 - (A) - Ice cube

provocation test (Ice cube test) for diagnosis of cold urticaria; (B) -

Positive “ice cube” challenge test for cold urticaria. HUCFF-UFRJ Immunology

Service Courtesy

Image 3 – (A) Temp

Test® -Instrument aimed at provocation testing in cold urticaria and heat urtica-ria; (B) Carrying out the specific provocation test

for cold urticaria through TempTest®. HUCFF-UFRJ

Immunology Service Courtesy

Delayed Pressure

Urticaria (DPU) is a condition in which deep tissue swelling occurs several

hours after a sustained pressure stimulus, for example, wearing a mouthguard,

prolonged adherence to sports equipment, on the soles of the feet after

running, or on the buttocks after long-distance cycling or rowing. The

therapeutic response is variable to antihistamines and the use of quadrupled

doses is often necessary. Omalizumab, dapsone, sulfasalazine, anti-TNF, and

theophylline have also been used to control DPU symptoms [54,57,58].

Solar urticaria

occurs in individuals shortly after exposure to the sun. Management includes

barrier protection, use of sunscreens, and antihistamines before sun exposure.

Different therapeutic modalities were described, according to the intensity of

the symptoms: sunscreen, oral antihistamines, cyclosporine, desensitization

with different types of phototherapy, omalizumab,

plasmapheresis, Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IgIV), afamelanotide, among others. Although therapeutic

recommendations have been proposed in the context of chronic urticarias, there

are no consensus-based guidelines that define the specific approach for solar

urticarial [54,57].

Aquagenic

urticaria is uncommon and represents a body's reaction to water; this is

independent of temperature. H1 antihistamines and UV therapy are used to treat

this disease with variable response [54,57].

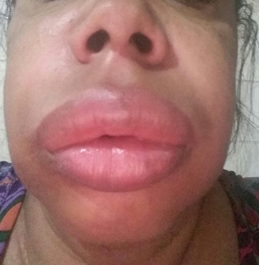

Hereditary angioedema

Hereditary

angioedema (HAE) is a rare, potentially fatal disease characterized by attacks

of cutaneous edema, submucosal and not correlated with wheals (image 5).

Patients with HAE have a quantitative or qualitative defect in the C1 inhibitor

(C1-INH), an enzyme from the SERPINA superfamily that acts as a serine

protease. Later a new group of HAE patients with normal C1-INH has been defined

[58].

Image 4 - Large

angioedema in a patient with Hereditary Angioedema; UCFF-UFRJ Immunology

Service Courtesy

Three types of

HAE are defined: 1) HAE with quantitative C1-INH deficiency (formerly

designated as HAE C1-INH Type I); 2) HAE with C1-INH dysfunction (formerly

designated as HAE C1-INH of Type II); and AEH with normal C1-INH (formerly

referred to as AEH Type III) [58,59,60].

The main

mediator of angioedema in patients with HAE-1/2 is bradykinin through the binding

of this mediator to its B2 receptor, which is constitutively expressed in

endothelial cells and interferes with endothelial junctions, increasing

vascular permeability [61].

Patients with

HAE suffer from recurrent angioedema episodes involving the skin and submucosa

of various organs. The most affected sites are the face, extremities,

genitalia, oropharynx, larynx, and digestive system. However, rare clinical

manifestations such as severe headache, urinary retention, and acute pancreatitis

can also occur [61].

Although many of

the crises occur spontaneously, several triggering factors have been

identified: trauma (even if mild), stress, infection, menstruation, pregnancy,

alcohol consumption, extreme temperature changes, exercise, use of ACE

inhibitors, and use of estrogen (contraceptives and hormone replacement

therapy). In adolescence, there may be a substantial increase in disease

activity, particularly in young females, due to menstrual cycles and the use of

oral contraceptives containing estrogen. As trauma is among the main triggering

causes of crises, impact/combat physical activities should be discouraged for

these patients [61].

HAE can present

with non-anaphylactic edema of the upper airways, which can cause suffocation

and death in athletes, as reported in an undiagnosed patient who practiced

martial arts as well as his family members [61]. Pharmacological treatment for

anaphylaxis is ineffective and airway management should not be delayed. If not

diagnosed, mortality can reach 33% [62,63].

All patients

with suspected AEH-1/2 (ie, recurrent angioedema in

the absence of a known cause) should be evaluated for blood levels of C4,

C1INH, and C1INH function; and these tests, if abnormally low, should be

repeated to confirm the diagnosis.

Education and

guidance are the most important initial actions to avoid serious consequences

of HAE and to improve the quality of life of patients and their families.

Patients should receive written information that is relevant about the HAE,

including preventive measures and an action plan for crisis management [59].

Identifying and

eliminating triggers such as stress and trauma can reduce the risk of seizures.

High-impact sports and hobbies that are at risk of trauma are contraindicated,

as are medications that can induce or prolong an HAE crisis, such as ACE

inhibitors, Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), estrogen-containing

medications, and gliptins. Patients who need contraception should only receive

progestins. Vaccination against hepatitis A and B is recommended, as blood

products can be used in the treatment of HAE, although there is no record of

infection by these viruses in patients who used the drugs currently available

[59].

HAE

pharmacotherapy is divided into three modalities: long-term prophylaxis,

short-term prophylaxis, and treatment of crises. As this article is a

bibliography for sports emergencies, we took a moment to discuss the treatment

of angioedema crises in these patients.

Conclusion

Physical

activities can trigger different illnesses (asthma, rhinitis, anaphylaxis,

urticaria, and hereditary angioedema) that impair performance. The early

diagnosis of immunoallergic disorders in athletes is important in order to

implement effective preventive measures and rescue strategies, allowing the

full performance of physical activities.

Potential conflict of

interest

No potential conflicts

of interest relevant to this article have been reported.

Financing source

There were no external

funding sources for this study.

Author contributions

Conception and design

of the research: Dortas-Jr

SD. Data collection: Dortas-Jr SD, Azizi

G. Data analysis and interpretation: Dortas-Jr SD, Azizi G. Statistical analysis: Not

applicable. Writing of the manuscript: Dortas-Jr SD,

Azizi G. Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Dortas-Jr SD, Azizi G

References

- Parsons JP, Hallstrand TS, Mastronarde JG, Kaminsky DA, Rundell

KW, Hull JH, et al. An official American thoracic society clinical practice

guideline: Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2013;187(9):1016-27. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201303-0437ST [Crossref]

- Kippelen P, Anderson S. Pathogenesis of exercise induced bronchoconstriction. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am 2013;33:299‑312. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2013.02.002 [Crossref]

- Langdeau JB, Turcotte H, Bowie DM, Jobin J, Desgagné P, Boulet LP. Airway hyperresponsiveness in elite athletes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:1479-84. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9909008 [Crossref]

- Correia MA Jr, Rizzo JA, Sarinho SW, Cavalcanti Sarinho ES, Medeiros D, Assis F. Effect of exercise-induced bronchospasm and parental beliefs on physical activity of asthmatic adolescents from a tropical region. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2012;108(4):249-53. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.01.016 [Crossref]

- Sano F, Solé D, Naspitz CK. Prevalence and characteristics of exercise induced asthma in children. Pediatr Allerg Pediatr Allergy Immunol 1998;9(4):181-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1998.tb00370.x [Crossref]

- Weiler JM, Anderson SD, Randolph C, Bonini S, Craig TJ, Pearlman DS, et al. Pathogenesis, prevalence, diagnosis, and management of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: a practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2010;105(Suppl):S1-S47. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.09.021 [Crossref]

- Fitch KD, Sue-Chu M, Anderson SD, Boulet S, Hancox RJ, McKenzie D, et al. Asthma and the elite athlete: summary of the International Olympic Committee’s consensus conference, Lausanne, Switzerland, January 22-24, 2008. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;122:254-60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.003 [Crossref]

- Bonsignore MR, Morici G, Vignola AM, Riccobono L, Bonanno a., Profita M, et al. Increased airway inflammatory cells in endurance athletes: What do they mean? Clin Exp Allergy 2003;33(1):14-21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01557.x [Crossref]

- Anderson SD, Kippelen P. Exercise induced bronchoconstriction: pathogenesis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2005;5:116-22. doi: 10.31189/2165-6193-5.3.37 [Crossref]

- Helenius I, Haahtela T. Allergy and asthma in elite summer sport athletes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000;106(3):444-52. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.107749 [Crossref]

- Pedersen BK, Ullum H. NK cell response to physical activity: possible mechanisms of action. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1994;26(2):140-6. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199402000-00003 [Crossref]

- Walsh NP, Gleeson M, Shephard RJ, Woods JA, Bishop NC,

Fleshner M, et al. Position statement. Part one:

Immune function and exercise. Exerc Immunol Rev 2011;17:6-63

- Azizi GG, Orsini M, Dortas Júnior SD, Vieira PC, Carvalho RS, Pires CSR, et al. COVID-19 e atividade física: qual a relação entre a imunologia do exercício e a atual pandemia? Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc 2020;19(2supl):S20-S29. doi: 10.33233/rbfe.v19i2.4115 [Crossref]

- Dickinson J, McConnell A, Whyte G. Diagnosis of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: eucapnic voluntary hyperpnoea challenges identify previously undiagnosed elite athletes with exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Br J Sports Med 2010;45(14):1126-31. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.072520 [Crossref]

- Subbarao P, Duong M, Adelroth E, Inman M, Pedersen S, O’Byrne PM, et al. Effect of ciclesonide dose and duration of therapy on exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;117:1008-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.048 [Crossref]

- Fitch KD, Morton AR. Specificity of exercise in exercise-induced asthma. BMJ 1971;4:577-81. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5790.814-c [Crossref]

- Global Initiative for Asthma. [Internet] 2020. [cited

2020 Nov 15]. Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org

- Silva D, Couto M, Delgado L, Moreira A. Diagnosis and treatment of asthma in athletes. Breathe 2012;8(4):287-96. doi: 10.1183/20734735.009612 [Crossref]

- Millqvist E, Bengtsson U, Löwhagen O. Combining a beta2-agonist with a face mask to prevent exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Allergy 2000;55:672-5. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00558.x [Crossref]

- Elkins MR, Brannan JD. Warm-up exercise can reduce exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:657-8. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091725 [Crossref]

- World Anti-doping Agency. [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 13]. https://www.wada-ama.org

- Autoridade

Brasileira de Controle de Dopagem. [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov

13]. https://www.gov.br/abcd/pt-br

- Duong M, Amin R, Baatjes AJ, Kritzinger F, Qi Y, Meghji Z, Lou W, et al. The effect of montelukast, budesonide alone, and in combination on exercise induced bronchoconstriction. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;130:535-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.051 [Crossref]

- Jutel M, Agache I, Bonini S, Burks AW, Calderon M, Canonica W, et al. International consensus on allergy immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136(3):556-68. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.04.047 [Crossref]

- Christensen P, Thomsen SF, Rasmussen N, Backer V, et

al. Exercise induced laryngeal obstructions objectively assessed using EILOMEA.

Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2010;267:401-7. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-1113-6 [Crossref]

- Nielsen EW, Hull JH, Backer V. High prevalence of exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2013;45(11):2030–5. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318298b19a [Crossref]

- Rundell KW,

Wilber RL, Szmedra L, Jenkinson DM, Mayers LB, Im J. Exercise induced

asthma screening of elite athletes: field versus laboratory exercise challenge.

Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32:309-16. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200002000-00010

- Lakin RC, Metzger WJ, Haughey BH. Upper airway obstruction presenting as exercise-induced asthma. Chest 1984;86(3):499–501. doi: 10.1378/chest.86.3.499 [Crossref]

- Johansson H, Norlander K, Berglund L, Janson C, Malinovschi A, Nordvall L, Nordang L, et al. Prevalence of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction and exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction in a general adolescent population. Thorax 2015;70(1):57–63. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205738 [Crossref]

- Zealear DL, Billante CR. Neurophysiology of vocal fold paralysis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2004;37(1):1–23. doi: 10.1016/S0030-6665(03)00165-8 [Crossref]

- Halvorsen T, Walsted ES, Bucca C, Bucca C, Bush A, Cantarella G, et al. Inducible laryngeal obstruction (ILO) - an official joint European Respiratory Society and European Laryngological Society statement. Eur Respir J 2017;50. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02221-2016 [Crossref]

- Hull JH, Backer V, Gibson PG, Fowler SJ. Laryngeal

dysfunction - assessment and management for the clinician. Am J Respir Crit

Care Med 2016;194(9):1062-72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201606-1249C [Crossref]I

- Lakin RC, Metzger WJ, Haughey

BH. Upper airway obstruction presenting as exercise-induced asthma. Chest

1984;86(3):499-501. doi: 10.1378/chest.86.3.499 [Crossref]

- Morris MJ, Deal LE, Bean DR, Grbach VX, Morgan JA. Vocal cord dysfunction in patients with exertional dyspnea. Chest 1999;116(6):1676-82. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.6.1676 [Crossref]

- Ben-Shoshan M, Clarke AE. Anaphylaxis: past, present and future. Allergy 2011;66(1):1-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02422.x [Crossref]

- Kim H, Fischer D. Anaphylaxis. Allergy, Asthma Clin

Immunol 2011;7(Suppl 1):1-7.

- Muraro A, Roberts G, Worm M, Bilò MB, Brockow K, Fernández Rivas M, et al. Anaphylaxis: Guidelines from the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Allergy. 2014;69(8):1026-45. doi: 10.1111/all.12437 [Crossref]

- McNeil BD, Pundir P, Meeker S, Han L, Undem BJ, Kulka M, et al. Identification of a mast-cell-specific receptor crucial for pseudoallergic drug reactions. Nature. 2015;519(7542):237-41. doi: 10.1038/nature14022 [Crossref]

- Gonçalves DG, Giavina-Bianchi P. Receptor MrgprX2 nas anafilaxias não alérgicas. Arq Asma Alerg Imunol 2018;2(4). doi: 10.5935/2526-5393.20180056 [Crossref]

- Guia

para manejo da anafilaxia-2012 – Grupo de Anafilaxia da ASBAI. Rev

Bras Alerg Imunopatol

2012;35(2).

- Ben-Shoshan M, Clarke AE. Anaphylaxis: past, present and future. Allergy 2011;66(1):1-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02422.x [Crossref]

- Maulitz RM, Pratt DS, Schocket AL. Exercise-induced anaphylactic reaction to shellfish. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1979;63(6):433-4. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(79)90218-5 [Crossref]

- Miller CWT, Guha B, Krishnaswamy G. Exercise-induced anaphylaxis: a serious but preventable disorder. Phys Sportsmed 2008;36(1):87-94. doi: 10.3810/psm.2008.12.16 [Crossref]

- Shadick NA, Liang MH, Partridge AJ, Bingham C, Wright E, Fossel AH, et al. The natural history of exercise-induced anaphylaxis: Survey results from a 10-year follow-up study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104(1):123-7. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70123-5 [Crossref]

- Wong GK, Krishna MT. Food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis: Is wheat unique? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2013;13(6):639-44. doi: 10.1007/s11882-013-0388-2 [Crossref]

- Bianchi A, Di Rienzo Businco A, Bondanini F, Mistrello G, Carlucci A, Tripodi

S. Rosaceae-associated exercise-induced anaphylaxis with positive SPT and

negative IgE reactivity to Pru

p 3. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;43(4):122-4.

- Matsuo H, Morimoto K, Akaki T, Kaneko S, Kusatake K, Kuroda T, et al. Exercise and aspirin increase levels of circulating gliadin peptides in patients with wheat-dependent exercise induced anaphylaxis. Clin Exp Allergy 2005;461-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02213.x [Crossref]

- Geller M. Anafilaxia induzida por exercício. Braz J Allergy Immunol 2015;3(2). doi: 10.5935/2318-5015.20150010 [Crossref]

- Giannetti MP.

Exercise-induced anaphylaxis: literature review and recent updates. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2018;18(12):72. doi: 10.1007/s11882-018-0830-6 [Crossref]

- Asaumi T, Yanagida N, Sato S, Shukuya A, Nishino M, Ebisawa M. Provocation tests for the diagnosis of food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2016;27(1):44-9. doi: 10.1111/pai.12489 [Crossref]

- Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, Abdul Latiff AH, Baker D, Ballmer-Weber B, et al. The EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria. Allergy 2018;73:1393-414. doi: 10.1111/all.13397 [Crossref]

- Schwartz LB, Delgado L, Craig T, Bonini S, Carlsen KH, Casale TB, et al. Exercise-induced hypersensitivity syndromes in recreational and competitive athletes: a PRACTALL consensus report (what the general practitioner should know about sports and allergy). Allergy 2008;63(8):953-61. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01802.x [Crossref]

- Dortas Junior SD, Azizi GG, Sousa ACMCFF, Lupi O, França AT, Valle SOR. Urticárias crônicas induzidas: revisão do tema. Arq Asma Alerg Imunol 2020. doi: 10.5935/2526-5393.20200047 [Crossref]

- Fukunaga A, Washio K, Hatakeyama M, Oda Y, Ogura K, Horikawa T, Nishigori C. Cholinergic urticaria: epidemiology, physiopathology, new categorization, and management. Clin Auton Res 2018;28(1):103-13. doi: 10.1007/s10286-017-0418-6 [Crossref]

- Magerl M, Altrichter S, Borzova E, et al. The definition, diagnostic testing, and management of chronic inducible urticarias – TheEAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/UNEV consensus recommendations 2016 update and revision. Allergy 2016;71(6):780-802. doi: 10.1111/all.12884 [Crossref]

- Del Giacco SR, Carlsen KH, Du Toit G. Allergy and sports in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2012;23(1):11-20. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01256.x [Crossref]

- Dortas Junior S, Azizi G, Valle S. Efficacy of omalizumab in chronic spontaneous urticaria associated with chronic inducible urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2020;125(4):486-7. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.06.011 [Crossref]

- Busse PJ, Christiansen SC. Hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med 2020;382(12):1136-48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1808012 [Crossref]

- Giavina-Bianchi P, Arruda LK, Aun MV, Campos RA, Chong-Neto HJ, Constantino-Silva RN, et al. Diretrizes brasileiras para o diagnóstico e tratamento do angioedema hereditário - 2017. Arq Asma Alerg Imunol 2017;1(1):23-48. doi: 10.5935/2526-5393.20170005 [Crossref]

- Ariano A, D'Apolito M, Bova M, Bellanti F, Loffredo S, D'Andrea G, et al. A myoferlin gain-of-function variant associates with a new type of hereditary angioedema. Allergy 2020;75(11):2989-92. doi: 10.1111/all.14454 [Crossref]

- Ashrafian H. Hereditary angioedema in a martial arts family. Clin J Sport Med 2005;15(4):277-8. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000171884.12174.6a [Crossref]

- Valle SOR, Alonso MLO, Tortora RP, Abe AT, Levy SAP, Dortas SD Jr. Hereditary angioedema: Screening of first-degree blood relatives and earlier diagnosis. Allergy Asthma Proc 2019;40(4):279-281. doi: 10.2500/aap.2019.40.4213 [Crossref]

- Maurer M, Magerl M, Ansotegui I, Aygören-Pürsün E, Betschel S, Bork K, et al. The international WAO/EAACI guideline for the management of hereditary angioedema-The 2017 revision and update. Allergy 2018;73(8):1575-96. doi: 10.1111/all.13384 [Crossref]