Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc 2021;20(5):562-73

doi: 10.33233/rbfex.v20i5.4877

REVIEW

Acute inflammatory responses to flexibility training:

a systematic review

Respostas

inflamatórias agudas ao treinamento de flexibilidade: uma revisão sistemática

Carlos

José Nogueira1,2,3, Andrea Dos Santos Garcia3, Isabelle

Vasconcellos de Souza1, Antônio Carlos Leal Cortez1,3,4,

Gilmar Weber Senna1,3,5, Paula Paraguassu Brandão3, Estélio Henrique Martin Dantas1,3

1Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de

Janeiro (UNIRIO), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

2Força Aérea Brasileira (FAB), Escola

Preparatória de Cadetes do Ar (EPCAR), Barbacena, MG, Brazil

3Universidade Tiradentes (UNIT), Aracaju,

SE, Brazil

4Centro Universitário Santo Agostinho

(UNIFSA), Teresina, PI, Brazil

5Universidade Católica de Petrópolis,

Petrópolis, RJ, Brazil

Received:

August 10, 2021; Accepted: September

30, 2021.

Correspondence: Carlos José Nogueira, Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio

de Janeiro (UNIRIO), Laboratório de Biociências da Motricidade Humana (LABIMH),

Rua Dr. Xavier Sigaud, 290 / Sala 301, Praia

Vermelha, Rio de Janeiro RJ

Andrea dos Santos Garcia: andrea-sgarcia@hotmail.com

Isabelle Vasconcelos de Souza: isav2206@gmail.com

Antônio Carlos Leal Cortez: antoniocarloscortez@hotmail.com

Gilmar Weber Senna: gilmar.senna@ucp.br

Paula Paraguassu Brandão: pb.paula@yahoo.com.br

Estélio Henrique Martin Dantas:

estelio@pesquisador.cnpq.br

Abstract

Objective: The aim of the study was to

systematically assess the scientific evidence available on the effectiveness

and safety of flexibility training at different intensities in terms of acute

inflammatory responses in adult men. Methods: A search was conducted in

the Medline/PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science and Scopus databases and a

manual search in the reference lists of relevant studies. The research question

and strategy used were based on the PICO model. Included were studies involving

adults aged between 18 and 45 years, published in English, Spanish and

Portuguese, with no restriction for year of publication. Results: A

total of 1014 articles were initially recovered. After duplicates were

eliminated, 655 references were analyzed by title and abstract, 16 of which

were included for reading in their entirety. After this stage, 13 references

were excluded. At the end, three studies were considered eligible. Conclusion:

The evidence available suggests that stretching exercises maximum in

combination with non-habitual eccentric exercise or applied alone, are

associated with a possible acute inflammatory response. Based on the evidence

and the quality of the articles included in this review, the results should be

interpreted with caution. Future research with better methodological quality

involving the variables studied may better explain the results obtained to

date.

Keywords: exercises; muscle stretching exercises; flexibility; inflammation.

Resumo

Objetivo: O objetivo do estudo foi avaliar

sistematicamente as evidências científicas disponíveis sobre a eficácia e

segurança do treinamento de flexibilidade em diferentes intensidades sobre as

respostas inflamatórias agudas em homens adultos. Métodos: Foi realizada

uma busca nas bases de dados Medline/PubMed, Cochrane

Library, Web of Science e Scopus e uma busca manual

nas listas de referências de estudos relevantes. A questão de pesquisa e a

estratégia utilizadas foram baseadas no modelo PICO. Foram incluídos estudos

envolvendo adultos com idade entre 18 e 45 anos, publicados nos idiomas inglês,

espanhol e português, sem restrição de ano de publicação. Resultados: Um

total de 1.014 artigos foram recuperados inicialmente. Após a eliminação das

duplicatas, foram analisadas 655 referências por título e resumo, das quais 16

foram incluídas para leitura na íntegra. Após essa etapa, 13 referências foram

excluídas. Ao final, 3 estudos foram considerados elegíveis. Conclusão:

As evidências disponíveis sugerem que exercícios de alongamento máximo em

combinação com exercícios excêntricos não habituais ou aplicados isoladamente

estão associados a uma possível resposta inflamatória aguda. Com base nas

evidências e na qualidade dos artigos incluídos nesta revisão, os resultados

devem ser interpretados com cautela. Pesquisas futuras com melhor qualidade

metodológica envolvendo as variáveis estudadas podem explicar melhor os

resultados obtidos até o momento.

Palavras-chave: exercícios; exercícios de alongamento

muscular; flexibilidade; inflamação.

Introduction

Flexibility

training is considered a form of physical activity used by athletes, patients

in rehabilitation and individuals engaged in physical activities [1]. Control

of flexible training intensities enables differentiating between submaximal

(stretching) and maximal (flexibilizing) exercises,

which is essential to good physical planning and preparation [2,3].

Movement in

submaximal stretching occurs within the normal joint range, slightly sustained,

without pain or discomfort; in stretching exercises maximum, the muscle is

stretched to the point of discomfort, a little before the pain threshold [4,5].

According to Behm et al. [6], four main stretching exercises

techniques can be applied: static, dynamic, ballistic, and proprioceptive

neuromuscular facilitation (PNF). The static technique involves a continuous

controlled movement for the range of final motion of a single or multiple

joints actively contracting the agonist muscles (active static) or using

external forces such as gravity, a partner or stretching aids (passive static).

In the final position, the individual maintains the muscle in a stretched

position for a certain time [6].

The magnitude of

the moment of force (or torque) that will be applied to a joint or set of joints

during flexibility training is characterized as intensity, while the number of

sets and time are the dimensions of volume [7]. Special importance should be

attributed to training intensity, since a small moment of force may result in a

viscoelastic response of the locomotor apparatus with little or no gain in

range of motion. However, applying excessive force may compromise the tissue,

resulting in inflammation or even injury [7,8].

An experiment

with adult male mice reported high neutrophil levels after passive stretching

exercises maximum protocol, exhibiting an acute inflammatory response, given

that activated neutrophils secrete proinflammatory cytokines such as

interleukin 1 beta (IL-1b),

tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) [9]. This

inflammatory response to training plays an essential role in energy metabolism,

skeletal muscle repair and remodeling, and anabolic/catabolic response, and may

respond differently according to exercise type, intensity, volume, and recovery

between the exercise phases [10].

Thus, different

substrates of the inflammatory response are produced and secreted, such as

cytokines, which belong to a group of regulatory glycoproteins produced by

leukocytes and tissues such as the skeletal muscles [11] and are responsible

for the interconnections between immunological cells as a response to infection

or tissue damage, with possible proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory activity

[12,13].

Evidences on

the inflammatory responses caused by flexibility training are scarce in the

literature. This hampers a better understanding of the physiological mechanisms

of adaptation resulting from alterations in this methodological training

variable and the monitoring of adaptive responses to establish a balance

between the overload applied and recovery [14].

Thus,

investigating the inflammation resulting from flexibility training may

complement the information presented by traditional tissue injury markers

already evident in the literature, such as creatine kinase (CK) or

delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) [15].

Therefore, the

aim of the present review was to systematically assess and summarize the

scientific evidence available regarding the effectiveness and safety of

flexibility training at different intensities (maximal and submaximal) on acute

inflammatory responses in adult men.

Methods

The systematic

search in the literature was conducted in line with the guidelines of the

PRISMA Statement reports for systematic reviews and meta-analysis [16] and the

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [17]. The current

review was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic

Reviews (PROSPERO), under protocol number 42020165515, and entitled “Acute

inflammatory responses to stretching”.

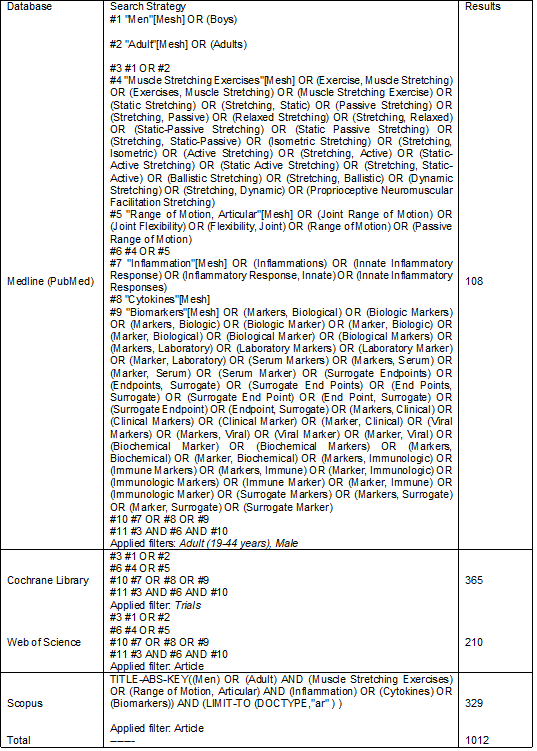

Search strategy

A search was

conducted in the following electronic databases: Medical Literature Analysis

and Retrieval System Online (Medline, via PubMed), Cochrane Library, Web of

Science and Scopus. The search strategies created and used for the databases

are presented in Table I. A manual search was carried out in the reference

lists of the relevant studies to identify eligible articles not found in the

electronic search. The searches were performed in June 2020 and update in July

2021.

The

following descriptors were selected in the Descritores

em Ciências da Saúde (DeCS) and Medical Subject

Headings (MeSH) databases: homens

(men), adulto (adult), exercícios

de alongamento muscular (muscle stretching

exercises), amplitude de movimento articular (joint

range of motion), inflamação (inflammation), citocinas (cytokines), biomarcadores

(biomarkers), as described and presented along with the search strategy used in

Medline via Pubmed and adapted to other databases

(Chart 1).

Chart 1 - Strategies

used for electronic searches

Source: Author 2020

Research question

The research

question and strategy used in this study were based on the Population,

Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) model, commonly applied in

evidence-based practice and recommended for systematic reviews [18].

Thus, adult men,

trained or not in flexibility, were used as the “Population”; for Intervention,

studies involving different intensities of flexibility training were

considered, for Control, the “not applicable” criterion was adopted; and

“Outcomes” were the primary and secondary outcomes of acute inflammatory

responses caused by flexibility training exercises. Thus, the final PICO

question was “Does flexibility training at different intensities increases the

acute inflammatory response in adult men?

Eligibility criteria

Included were

studies involving adults aged between 18 and 45 years and complete articles

published in English, Spanish and Portuguese. There was no restriction for year

of publication.

With respect to

study designs, given the limited number of studies published to date and that

the aim of this review was to map knowledge, randomized and non-randomized

(quasi-experimental) clinical studies were included.

The following

exclusion criteria were established: studies other than randomized, quasi-randomized

or experimental clinical trials, studies involving older adults, children,

individuals with disabilities, limitations, or chronic diseases; studies with

high-performance athletes and those using animal models.

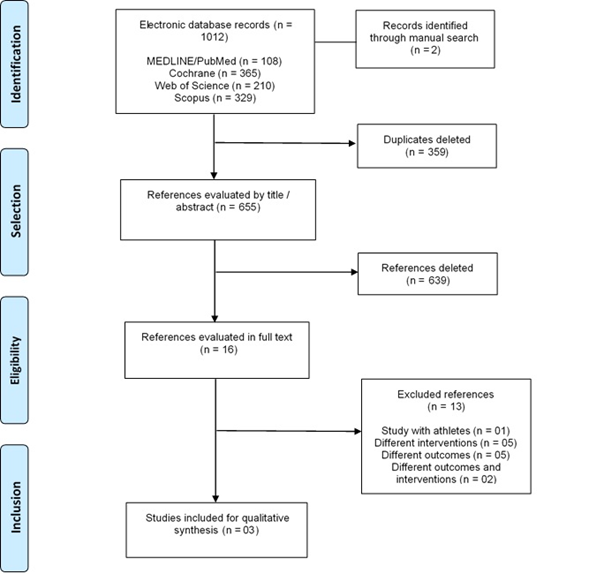

Study selection

The study

selection process was performed by two independent reviewers, with disagreement

resolved by a third reviewer. The articles were selected in two stages. In the

first stage, titles and abstracts of the references identified in the search

were assessed and the potentially eligible studies were pre-selected. In the

second stage, the entire text of the pre-selected studies was evaluated to

confirm eligibility. The selection process was conducted using the Rayyan

platform (https://rayyan.qcri.org) [19]. The entire inclusion and exclusion

process was in accordance with the PRISMA FLOW stages, illustrated in Figure 1.

Studies included

After the

selection process, the following studies were included: one randomized clinical

trial [20] and two quasi-experimental non-randomized studies [8,21].

Data extraction

Standardized

electronic forms were used for this stage. The reviewers independently

extracted data related to the morphological characteristics of the studies, interventions and results. The differences were resolved by

consensus. The following data were initially collected: authors, year of

publication, type of study, sample (number of participants), methods,

intervention protocol and control group (if applicable), outcomes assessed,

results and conclusions.

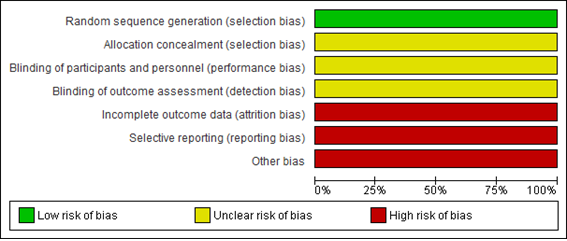

Assessment of the methodological quality of the

studies included

The

methodological quality and/or risk of bias of the studies were independently

assessed by two reviewers using the appropriate tools for each study design, as

follows: randomized clinical trial - Cochrane risk of bias [22], non-randomized

or quasi-experimental clinical trials - ROBINS-I [23]. The assessment of risk

of bias of randomized clinical trials is summarized in Figure 2 and of

non-randomized or quasi-experimental trials in Table II.

Results

Search results

The search

produced 1014 studies. After duplicates were eliminated, 655 references were

analyzed by title and abstract, resulting in 16 inclusions (according to the

PICO question) for reading in their entirety. After this stage, 13 references

were excluded (different populations, interventions and/or outcomes). At the

end, three studies were considered eligible and analyzed. The flowchart of the

study selection process is presented in Figure 1, and Table I summarizes the

characteristics of these studies.

Adapted from Page et

al. [16]

Figure 1 - Flowchart

of the study selection process (PRISMA Flow)

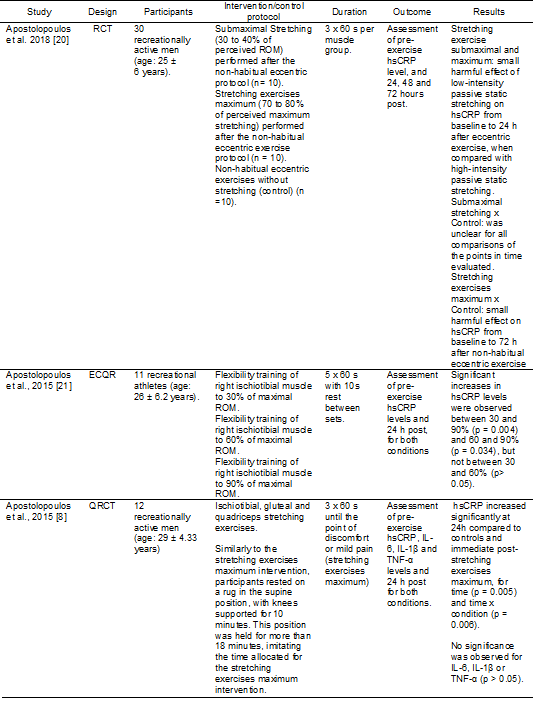

Study results

Since only one

randomized clinical trial was eligible for review [20], we were unable to

conduct a quantitative summary between the studies. Thus, a narrative approach

was more appropriate.

The qualitative

summary obtained for the acute inflammatory responses are presented in Table I.

Table I – Characteristics

of the studies included

RCT = Randomized

clinical trial; QRCT = Quasi-randomized clinical trial; hsCRP

= high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; ROM: Maximal range of motion; IL-6 =

Interleukin 6; IL-1b = Interleukin 1 beta; TNF-α = Tumor necrosis factor alfa

Risk of bias assessment

In general,

considering the Cochrane tool, the randomized clinical trial showed high risk

of bias and unclear risk in three domains, and low risk of bias only in the

random sequence generation domain, as shown in Figure 2. The quasi-experimental

studies according to the ROBINS-I tool exhibited a serious and critical risk of

bias in most of the domains assessed, and only one study showed low risk of

bias in the incomplete outcome data domain since data were missing, as

illustrated in Chart 2.

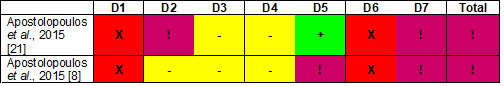

Figure 2 – Risk of bias of the

randomized clinical trial Apostolopoulos et al. 2018

[20], using the Cochrane Risk of Bias table

Chart 2 – Summary of the risk of bias

of non-randomized comparative studies, using the ROBINS-I tool

Green ( + ) = low risk of bias; Yellow ( - ) = moderate risk of

bias; Red (X) = serious risk of bias; Wine-colored ( ! ) = critical risk of

bias

Domains:

D1: Bias related to

confounding factors;

D2: Bias related to

participant selection;

D3: Bias related to

intervention classification;

D4: Bias related to

deviations from intended interventions;

D5: Bias related to

missing data;

D6: Bias related to

outcome assessment;

D7: Selection bias in

the report of results

Assessment certainty of evidence

We were unable

to assess certainty of evidence for the outcome of interest of the present

review, given that only one study (randomized clinical trial) evaluated the

effect magnitude.

Discussion

The evidence of

three clinical trials with available data whose primary and secondary outcomes

were the inflammatory effects caused by flexibility training at different

intensities: one randomized clinical trial [20] and two quasi-experimental

clinical trials [8,21].

Considering the

results of the randomized clinical trial for the outcome analyzed [20], there

was a small harmful effect of submaximal stretching at the hsCRP

concentrations assessed from baseline to 24 hours after eccentric exercise when

compared to stretching exercises maximum. The effects of submaximal stretching

compared to controls were unclear for all the comparisons at the assessment

times of hsCRP levels. However, there was a small

harmful effect of stretching exercises maximum compared to controls on hsCRP from baseline to 72h after non-habitual eccentric

exercise.

According to the

results of this randomized clinical trial [20], stretching exercises maximum

may have caused a slight inflammation, demonstrated by the increase in hsCRP concentrations after non-habitual eccentric exercise,

with statistically higher hsCRP values at 24 h versus

72 h (p = 0.012).

In one of the

quasi-experimental clinical trials, static flexibility training at different

maximal ROM (30, 60 and 90%) in the right ischiotibial

muscle promoted significant increases in hsCRP levels

between 30 and 90% (p = 0.004) and 60 and 90% (p = 0.034), but not between 30

and 60% (p > 0.05), revealing that increases in the percentage of maximal

ROM (intensity) are associated with a rise in hsCRP

levels, causing possible systemic inflammation [21].

In the second

quasi-experimental study, Apostolopoulos et al.

[8] observed that stretching exercises maximum with three 60-second sets of

static insistence to the point of discomfort or mild pain caused an acute

inflammatory response sustained by the significant increase in hsCRP at 24h compared to the control condition and

immediate post-stretching, for time (p = 0.005) and time x condition (p =

0.006). However, no significant increases were observed for inflammatory

markers IL-6, IL-1b or

an-α.

Comparing the

results of the studies included in this review showed that passive stretching

exercises maximum is associated with a likely increase in acute inflammatory

response. Thus, stretching exercises maximum promoted higher concentrations of hsCRP, as clearly demonstrated in the quasi-experimental

studies, in which flexibility training was applied alone, without resistance

exercise.

The force

generated by the acute stretch (mechanical stimulus) causes an excessive

overload of the contractile elements of the skeletal muscle, exceeding their

usual demands and inducing tissue damage [24]. Structurally, there is a

myofilament disarrangement in the sarcomeres, damage to the sarcolemma, loss of

fiber integrity and the subsequent leakage of muscle proteins into the blood

[25]. This functional change causes a reduction or loss of muscle strength and

is responsible for triggering an acute response [24].

The application

of this overload causes microtraumas of varying degrees in the striated

skeletal muscle tissue, connective tissue and bone

tissue. These microtraumas, considered as temporary and repairable damage,

result in an acute inflammatory response, instrumented by numerous specific

chemical mediators such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and the pro-inflammatory

cytokines IL-1b,

IL-6 and TNF-α, derivatives of the injured tissues [13,26,27,28,29]. The extent

of the inflammatory response is determined by the degree of muscle damage, the

magnitude of inflammation, and the lesion-specific interaction between the

invading inflammatory cells and the injured muscle [24,28].

Considering

intensity as an important parameter of flexibility training [26], evidence

indicates that the magnitude of force applied to the muscle during stretching

is a catalyst for tissue damage and inflammation [28,30,31] as observed in animals studies [9,32] and according to the results

presented in this review.

About the

applicability and quality of the evidence, the studies included in the present

review revealed high and critical risk of bias in assessment of the randomized

clinical and quasi-experimental trials [8,20,21], respectively.

However, the

findings of the present review need to be interpreted considering the following

limitations: few studies were eligible, with only one randomized controlled

trial and two quasi-experimental studies; the different study designs,

experimental protocols and controls, measures of results and incomplete data in

some of the studies hampered an additional quantitative synthesis; the

conclusions were based on relatively low-quality data and consequent high risk

of bias; and important methodological questions, such as the lack of allocation

concealment, group comparison at baseline of the participants and assessor

blinding, limited the strength of the study conclusions.

Conclusion

The evidence

available in randomized and non-randomized trials suggests that stretching

exercises maximum, in combination with non-habitual eccentric exercise, or

applied alone, is associated with an acute inflammatory response. However, the

estimates of these results are very low, which precludes definitive

conclusions. The limitations inherent to the design and methodological quality

(high or critical risk of bias) of the studies significantly reduced the

reliability of all the results presented. Thus, new studies with better

methodological quality, involving the variables studied, may better elucidate

the results obtained to date.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest

with relevant potential

Financing source

There were no external

sources of funding for this study.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design

of the research: Nogueira CJ, Senna GW, Dantas EHM;

Data collection: Nogueira CJ, Brandão PP, Souza IV,

Garcia, AS; Analysis and data interpretation: Nogueira CJ, Cortez ACL, Brandão PP, Souza IV, Garcia, AS; Statistical analysis: Not

applicable; Obtaining financing: Not applicable; Writing of the manuscript:

Nogueira CJ, Dantas EHM; Critical review of the

manuscript: Senna GW, Cortez ACL; Final revision of the manuscript: Nogueira

CJ, Brandão PP, Dantas EHM

Academic link

This study is linked to

the thesis of doctoral student Nogueira CJ, from the Stricto

Sensu Post-Graduation Program in Nursing and

Bioscience, Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de

Janeiro (UNIRIO), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

References

- Garber CE, Blissmer B,

Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, et al. Quantity and quality of

exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and

neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43(7):1334-59. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb [Crossref]

- Dantas EHM, Daoud R, Trott A, Nodari Júnior RJ, Conceição MCSC. Flexibility: components, proprioceptive mechanisms and methods. Biomed Hum Kinet 2011;(3):39-43. doi: 10.2478/v10101-011-0009-2 [Crossref]

- Dantas EHM, Conceição MCSC. Flexibility: myths and facts. J Phys Education 2017;86(4):279-83. doi: 10.37310/ref.v86i4.470 [Crossref]

- Nogueira CJ, Galdino AS, Cortez ACL, Vasconcelos Souza I, Mello DB, Senna GW, et al. Effects of flexibility training with different volumes and intensities on the vertical jump performance of adult women. J Phys Educ Sport (JPES) 2019;19(3):1680-85. doi: 10.7752/jpes.2019.03244 [Crossref]

- Nogueira CJ, Galdino LAS, Vale RGS, Mello DB, Dantas EHM. Acute effect of the proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation method on vertical jump performance. Biomed Hum Kinet 2012;(2):1-4. doi: 10.2478/v10101-010-0001-2 [Crossref]

- Behm DG, Blazevich AJ, Kay AD, McHugh M. Acute effects of muscle stretching on physical performance, range of motion, and injury incidence in healthy active individuals: a systematic review. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2016;41(1):1-11. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0235 [Crossref]

- Jacobs CA, Sciascia AD. Factors That influence the efficacy of stretching programs for patients with hypomobility. sports health: a multidisciplinary approach 2011; 3(6):520-23. doi: 10.1177/1941738111415233 [Crossref]

- Apostolopoulos NC, Metsios GS, Taunton J, Koutedakis Y, Wyon M. Acute inflammation response to stretching: a randomised trial. Ita J Sports Reh Po 2015; 2(4): 368-81. doi: 10.17385/ItaJSRP.015.3008 [Crossref]

- Pizza FX, Koh TJ, McGregor SJ, Brooks SV. Muscle inflammatory cells after passive stretches, isometric contractions, and lengthening contractions. J Appl Physiol 2002; 92(5):1873-78. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01055.2001 [Crossref]

- Rossi FE, Gerosa-Neto J, Zanchi NE, Cholewa JM, Lira FS. Impact of short and moderate rest intervals on the acute immunometabolic response to exhaustive strength exercise. J Strength Cond Res 2016;30(6):1563-9. doi: /10.1519/JSC.0000000000001189 [Crossref]

- Peake JM, Della Gatta P,

Suzuki K, Nieman DC. Cytokine expression and secretion by skeletal muscle

cells: regulatory mechanisms and exercise effects. Exerc

Immunol Ver [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2021 Oct 27];(21):8-25.

Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25826432

- Ferreira VS, Muller BC, Achour Junior A. Acute effects of static versus dynamic stretching on the vertical jump performance of soccer players. Motriz: J Phys Ed 2013; 19(2):450-459. doi: 10.1590/S1980-65742013000200022 [Crossref]

- Silva FOC, Macedo DV. Physical exercise, inflammatory process and adaptive condition: an overview. Rev Bras Cineantropom Desempenho Hum 2011;13(4):320-8. doi: 10.5007/1980-0037.2011v13n4p320 [Crossref]

- Antunes

Neto JMF, Almeida EJP, Campos MF. Análise de marcadores celulares e bioquímicos

sanguíneos para determinação de parâmetros de monitoramento do treinamento de

praticantes de musculação. RBPFEX [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2021 Oct

27];11(70):778-83. Available from:

http://www.rbpfex.com.br/index.php/rbpfex/article/view/1266

- Brenner IK, Natale VM, Vasiliou P, Moldoveanu AI, Shek PN, Shephard RJ. Impact of three different types of exercise on components of the inflammatory response. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1999;80(5):452-60. doi: 10.1007/s004210050617 [Crossref]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372(71). doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [Crossref]

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston

M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of

Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). [Internet]. Cochrane, 2019.

[cited 2021 Oct 27]. Available from: http://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Santos CMDC, Pimenta CADM, Nobre MRC.The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2007;15(3):508-11. doi: 10.1590/S0104-11692007000300023 [Crossref]

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan: A web and mobile app for systematic

reviews. Systematic Reviews 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [Crossref]

- Apostolopoulos NC, Lahart IM, Plyley MJ, Taunton J, Nevill AM, Koutedakis Y, et al. The effects of different passive static stretching intensities on recovery from unaccustomed eccentric exercise - a randomized controlled trial. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2018;43(8):806-15. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2017-0841 [Crossref]

- Apostolopoulos NC, Metsios GS, Nevill AM, Koutedakis Y. Stretch intensity vs. inflammation: a dose-dependent association? IJKSS 2015;3(1):1-6. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijkss.v.3n.1p.27 [Crossref]

- Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JPT, Caldwell DM, Reeves BC, Shea B, et al. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;(69):225-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005 [Crossref]

- Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ (Online) 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [Crossref]

- Peake JM, Neubauer O, Della Gatta PA, Nosaka K. Muscle damage and inflammation during recovery from exercise. J Appl Physiol 2017:122(3),559-70. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00971.2016 [Crossref]

- Urso ML. Anti-inflammatory interventions and skeletal muscle injury: benefit or detriment? J Appl Physiol 2013;115(6):920-8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00036.2013 [Crossref]

- Apostolopoulos NC.

Stretching intensity and the inflammatory response - a paradigm shift. Switzerland: Springer Natures;

2018.

- Rocha

AL, Pinto AP, Kohama EB, Pauli JR, De Moura LP,

Cintra DE, et al. The proinflammatory effects of chronic excessive

exercise. Cytokine 2019;119:57-61. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2019.02.016 [Crossref]

- Silva

VF, Braga JC, Santos KM, Oliveira GL, Oliveira TAP, Teixeira AM, et al. Pain,

inflammation and performance can predict the ideal moment to apply new

overload. J Sport Sci [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Oct 27];14(1):32-41.

Available from: https://sportscience.ba/pdf/br27.pdf

- Pedersen BK. The physiology of optimizing health with a focus on exercise as medicine. Annu Rev Physiol 2019;81:607-27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-020518-114339 [Crossref]

- Antunes BM, Inoue DS, Lira FS, Rossi FE, Rosa-Neto JC. Imunometabolismo e exercício físico: uma nova fronteira do conhecimento. Motricidade 2017;13(1):85-98. https://doi.org/10.6063/motricidade.7941 [Crossref]

- Bessa AL, Oliveira VN, Agostini GG, Oliveira RJS, Oliveira ACS, White GE, et al. Exercise intensity and recovery: biomarkers of injury, inflammation, and oxidative stress. J Strength Cond Res 2016;30:311-9. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31828f1ee9 [Crossref]

- Berrueta L, Muskaj I, Olenich S, Butler T, Badger GJ, Colas RA, et al. Stretching impacts inflammation resolution in connective tissue. J Cell Physiol 2016;231(7):1621-27. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.25263 [Crossref]