Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc. 2024;23:e235437

doi: 10.33233/rbfex.v23i1.5437

REVIEW

Impact of Pilates on the quality

of life of

patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review

Impacto do Pilates na

qualidade de vida de pacientes com doença renal crônica: uma revisão

sistemática

Lucas Oliveira Soares1,2,

Wasly Santana Silva3, Beatriz Rodrigues

Mortari2, Adriana Malavasi Falleiros2, André Luis Lisboa Cordeiro1

1Centro Universitário Nobre, Feira de

Santana, BA, Brazil

2Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de

Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

3Hospital Universitário da Universidade

Federal de Sergipe, Aracaju, SE, Brasil

Received: August 19, 2023; Accepted:

September 19, 2023.

Correspondence: Lucas Oliveira Soares, lucassoaresft@gmail.com

How to cite

Soares LO, Silva WS, Mortari BR, Falleiros

AM, Cordeiro ALL. Impact of Pilates on the quality of life of patients with chronic

kidney disease: a systematic review. Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc 2024;23:e235437. doi:

10.33233/rbfex.v23i1.5437

Abstract

Introduction: The evolution

of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) is silent and

asymptomatic, which makes diagnosis and treatment

difficult in the initial phase. Patients with CKD present loss of

muscle mass, decreased functional capacity, and quality

of life (QoL). Objective: To review the effects

of the Pilates Method on the

QoL of patients

with CKD. Methods: This is a systematic

review carried out according

to PRISMA. The search was carried out in December 2022 in the following databases: Google

Scholar, Scielo, Lilacs,

CINAHL, Pubmed, PEDro, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Central Register of Systematic Review. To carry out the literary

search, the PICOT strategy was used,

and the studied

population was patients with CKD, the intervention was training with the Pilates method, compared with patients

who did not

undergo training or any other intervention,

the evaluated outcome was QoL

and we included

only randomized controlled clinical trials. Results: 3,287 articles were found,

of which 3 were considered eligible for our systematic review. Due to methodological heterogeneity, it was not possible to

perform a meta-analysis. All studies included

showed significant benefits of Pilates practice in the QoL of patients

with CKD. Conclusion:

Our results indicate that the

practice of physical exercise with the Pilates method can favor the improvement of QoL in individuals

with CKD.

Keywords: renal insufficiency,

chronic; Pilates; quality of life

Resumo

Introdução: A evolução da Doença Renal Crônica

(DRC) é silenciosa e assintomática, o que dificulta o diagnóstico e tratamento

na fase inicial. Pacientes com DRC apresentam perda de massa muscular,

diminuição da capacidade funcional e qualidade de vida (QV). Objetivo:

Revisar os efeitos do Método Pilates na QV de pacientes com DRC. Métodos:

Trata-se de uma revisão sistemática realizada de acordo com o PRISMA. A busca

foi realizada em dezembro de 2022 nas seguintes bases de dados Google

Acadêmico, Scielo, Lilacs,

CINAHL, Pubmed, PEDro, Web of science e o Cochrane Central

Register of Systematic

Review. Para execução da busca literária foi utilizada a estratégia PICOT, e a

população estudada foi paciente com DRC, a intervenção foi o treinamento com o

método Pilates, comparado com pacientes que não realizaram o treinamento ou

qualquer outra intervenção, o desfecho avaliado foi QV e incluímos apenas

ensaios clínicos controlados e randomizados. Resultados: Foram

encontrados 3.287 artigos, dos quais 3 foram considerados elegíveis para a

nossa revisão sistemática. Devido a heterogeneidade metodológica, não foi

possível realizar meta-análise. Todos os trabalhos incluídos mostraram

benefícios significativos da prática do Pilates na QV de pacientes com DRC. Conclusão:

Nossos resultados apontam que a prática de exercício físico com o método

Pilates pode favorecer a melhora da QV em indivíduos com DRC.

Palavras-chave: doença renal crônica; Pilates;

qualidade de vida.

Introduction

The evolution of Chronic

Kidney Disease (CKD) is silent and

asymptomatic, which makes the diagnosis difficult

in the initial phase, or even

late when the disease is already

advanced, making it an important public health problem [1]. Patients with CKD have significant physical inactivity [2,3], loss of muscle

mass [4], and decreased functional capacity [5], these systemic changes intrinsic to CKD cause deleterious effects, significantly affecting quality of life

(QoL).

Several factors such as myalgia, fatigue, sleep disorders, and sexual dysfunction contribute significantly to the decrease

in QoL [6]. In Brazil,

Jesus et al. [7] demonstrated that patients with

CKD have a significant impairment of QoL,

especially those on dialysis because

they are dependent on daily or

intermittent hemodialysis

(HD). In Iran, Ghiasi et al. [8] performed a systematic review with meta-analysis to summarize the

effects of CKD on QoL. The authors

evaluated data from more than 17,000 patients and found that

scores on the Short Form 36 (SF-36), Health-related Quality of Life (HRQOL), and Kidney Disease

Quality of Life-Short Form (KDQOL-SF) questionnaires were lower on

different dimensions compared to other

populations [8].

Physical exercise is suggested as the main strategy

to increase muscle strength, preventing or delaying

functional decline and QoL, a result already

demonstrated by the study by

Cheema [9]. In this scenario, Pilates appears, as an exercise modality

whose principles are breathing control, precision in execution, flexibility, activation of trunk stabilizing

muscles, and main focus on

the central muscles, diaphragm, and pelvic floor [10,11]. Pilates has already shown

that it can be effective in improving the QoL

of other populations [12,13], in addition,

it possibly has better adherence compared to other

exercise programs [14]. Therefore, our work aims to

review the effects of the Pilates Method on the

QoL of patients

with CKD.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic

review was completed following the Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines

[15]. It is registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematics (PROSPERO) with the number CRD42022369587.

Eligibility criteria

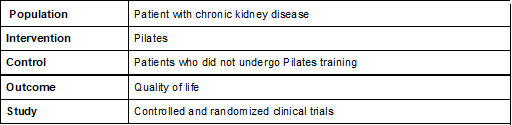

To carry out the literary search,

the PICOT strategy [16] was used, the

population studied was patients with

CKD, the intervention was training with the Pilates method, compared with patients

who did not

undergo training or any other intervention,

the evaluated outcome was QoL

and we only

included controlled and randomized clinical trials.

Articles with patients aged 18 years or older

with dialytic and non-dialytic CKD who performed physical

exercise with the Pilates method and specified which

movements were performed were included. As exclusion criteria, we defined

that studies that combined Pilates with another exercise

(aerobic, neuromuscular, inspiratory

muscle training, bodybuilding,

or hydrogymnastics) and those in which

patients had pathophysiological conditions that reduce performance during exercise (neuromuscular diseases, amputations, dementia).

The

complete strategy is shown in Chart 1. Randomized and controlled clinical trials were used, without

language and year restriction. The descriptors used were based on

DecS/Mesh: Renal Insufficiency, Chronic, Pilates, and Quality of

Life and their synonyms.

Chart 1 - PICOT strategy

[16]

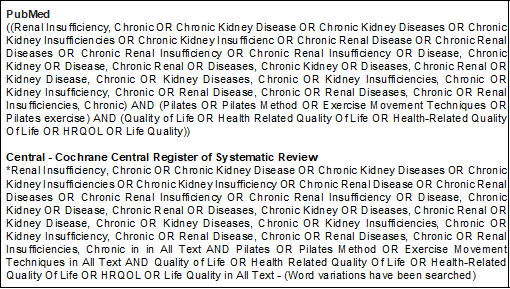

Database

We conducted a survey based on

the following databases: Google Scholar, Scielo,

Lilacs, Accumulated Index of Literature for Nurses and Other Health Professionals

(CINAHL), Pubmed, PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database), Web of Science, and the Cochrane Central Register

of Systematic Review. The survey was carried

out between December 5 and January 4, 2023.

Below we demonstrate the search strategy of the main

platforms we used to carry

out the Pubmed and Central review (Chart 2). The research

was based on the PICO strategy

[16] previously described and Boolean operators

AND and OR.

Chart 2 - Search strategy

in the main databases

Data items

The following data were extracted from the included studies:

(1) aspects of the study population,

such as number of patients, diagnosis;

(2) aspects of the intervention performed (sample size, type of Pilates movements, intensity, frequency, duration of training and duration of each

session); (3) follow-up; (4) outcome

measures; and (5) presented results.

Risk of

bias in individual studies

Methodological quality was assessed according

to the criteria

of the PEDro

scale [17], which scores 11

items, namely: 1- Eligibility criteria, 2 - Random allocation, 3 - Blind allocation,

4 - Baseline comparison, 5 - Blind individuals, 6 - Therapists blinded, 7 - Raters blinded, 8 - Appropriate

follow-up, 9 - Intent-to-treat analysis,

10 - Between-group comparisons,

11 - Point estimates and variability. Items are scored as present (1) or absent (0), generating a maximum sum of 10 points, the first item being disregarded.

Wherever possible, PEDro scores were drawn from the

PEDro database itself. When articles were not found

in this database, two independent and trained reviewers

evaluated the article with the

PEDro scale. Studies were considered

high quality if they scored 6 or

more. Studies with scores lower than 6 were

considered low quality.

Results

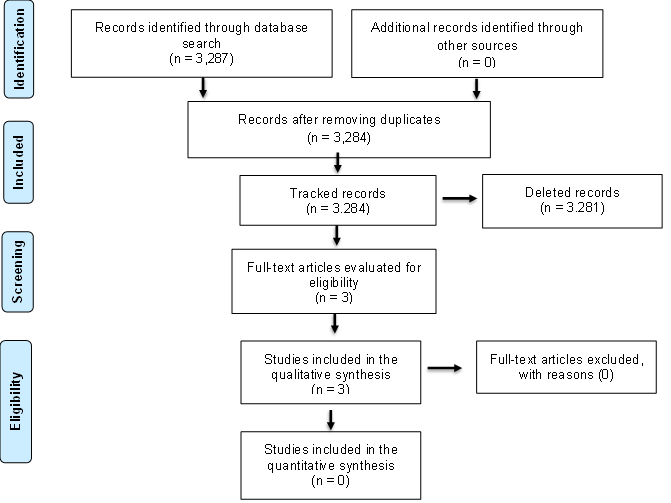

Selection and characteristics of the studies

After analyzing the articles found

in the search strategy, we realized

that some databases delivered generic results, thus increasing

the number of articles that

were excluded for not addressing the topic. At the

end of the

careful analysis, we included 3 studies

(Figure 1), totaling a sample of

170 individuals.

Figure 1 - Selection

process for studies included in the analysis

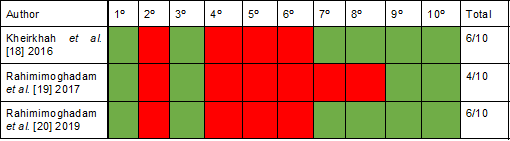

Methodological quality

To assess the methodological quality, the PEDro

scale [17] was used. Scores from two articles were

already available in the PEDro database,

except for Kheirkhah [24] which was evaluated

by 2 independent researchers (LO and WS). The

scores ranged from 4 to 6 points on a scale of 1 to

10 points (Chart 3). All studies

lost points on items related to

patient and therapist blinding.

Chart 3 - Methodological

quality of eligible studies (n = 3), PEDro scale

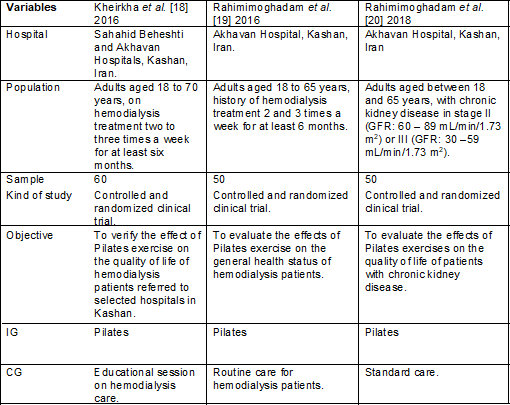

Characterization and results of the

studies

Chart 4 presents the sociodemographic

characteristics, and sample

distribution in the control group and

intervention group.

Chart 4 - Características gerais de cada

estudo, objetivo, população, grupo intervenção e controle

IG = intervention group; CG = group control; GFR = glomerular filtration rate

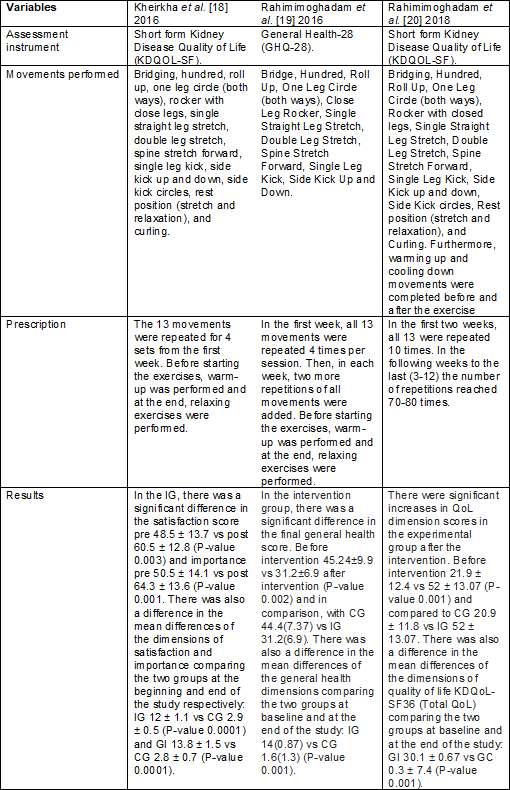

Chart 5

shows the evaluation and intervention protocols of each

study followed by the pre-

and post-intervention evaluation.

Chart 5 - Prescription

and study protocols: prescription and movements performed

IG = intervention group; CG = group control; GFR = glomerular filtration rate; QoL = quality of life;

U = Mann-Whitney test

Exercise protocols and progression

In the protocol by

Kheirhah et al. [18] all

13 movements were repeated four times per session and continued until

the end of

the program without changing the number of

repetitions and training duration. Rahimimoghadam et al.

[19], describe very well how the

progression of the exercises was

performed. In the first week, all

13 movements were repeated 4 times per session, and each week,

two more repetitions were added to

all movements, so in the 4th week,

all movements were performed 10 times, continuing until the end of

the program.

Corroborating with the previously mentioned studies, Rahimimoghadam et al. [20] describe

that the progression of the exercises was

based on the increase of

the repetitions and the duration

of the training time. The

time progressed according to the sessions,

the first two sessions lasted

45 minutes, and from the third session,

it was increased until it reached 70 minutes. In the first and

second sessions, the number of

exercises started with 10 repetitions and 45 minutes duration. In subsequent sessions, stretching exercises of about 5 minutes were added, Pilates exercises of 50 minutes and relaxation movements, of about

5 minutes. In these sessions

(sessions 3-12), the number of exercises

reached 70 to 80 repetitions with 70 minutes duration.

Pilates and quality of

life

Of the articles included in this systematic review [18,19,20], all showed a significant

increase in QoL in patients with CKD submitted to exercise

using the Pilates method compared to the control

group. The amount of movements performed

was similar between the studies, all

performed warm-up exercises prior to the start of training and relaxation exercises at the

end [18,19,20].

Discussion

This systematic

review of the literature identified, in all analyzed studies,

an increase in QoL related to

the practice of Pilates in individuals with CKD. The results were obtained through

questionnaires that assessed QoL through

the dimensions of physical health,

mental health, and CKD components. None of the studies

analyzed direct variables, such as functional capacity or metabolic

response in functional tests.

The quality analysis of the papers

showed moderate to low methodological

quality, which implies a reduction in their inference power.

The

Pilates method has diversified over time, with the extension of

its use in different contexts

and, currently, in different clinical conditions. Improvements in functionality and QoL in individuals undergoing Pilates have been described, from elderly people

with chronic musculoskeletal disorders [21] to women with

breast cancer [22]. In individuals with CKD, as far as we know,

this was the first systematic

review of the literature to assess

its effects on QoL. We identified

that the practice of Pilates improved self-reported functionality in terms of physical, instrumental activities of daily

living, and mental, possibly

acting in an inverse way to

the pathophysiology of CKD.

Among patients with CKD, the literature

has already well described a high prevalence of frailty

and morbidity, causing functional dependence or disability

[23]. The main consequence of this is

the decrease in QoL, which is

directly proportional to the increase

in age and the reduction in GFR, with an even more important

drop in those undergoing HD29. A cohort [24] of 5,888 people from the community

assessed functional disability among its participants. The presence of limitation in ADLs was almost

twice as high in participants

with CKD. In another study, Odden et al. [25],

a cohort of 1,024 participants with a mean age of 65 years, with stable

coronary disease, found that the

chances of low functional capacity were six times greater for participants with GFR less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Other consequences include a decrease in flexibility, strength, and muscle

tropism, with an impact on

low capacity in

instrumental activities of daily living [23].

Continuing with the previous thought,

we suggest that the main

physical benefits arising from the

practice of Pilates in CKD

are related to increased muscle strength and flexibility,

as reported in other studies [26,27], however, the evidence is

conflicting to argue improvement of cardiovascular conditioning and functional capacity [28]. Some observational

studies point to this improvement after 6 to 8 weeks

of training, but this evidence cannot

impute causality, mainly because they associated

the Pilates program with aerobic activities

[29,30]. In contrast, Sarmento et al. [31] verified in a study with patients hospitalized

with CKD, a greater advantage of Pilates concerning a conventional physiotherapy protocol in the outcomes of

functionality and functional capacity measured by an

incremental step test, in an

intragroup analysis. However, when an

extra group analysis was performed, there was no significant

difference between Pilates and conventional physical therapy. It is important to

highlight that, in the study by

Sarmento, due to its

nosocomial nature, the interventions lasted 10 consecutive days or less, invariably

insufficient time to evaluate the main

muscular and systemic adaptations to training with physical exercise.

Another important

point to highlight is the mental and

cognitive impacts caused by CKD. Studies demonstrate a dependent and independent

association between cognitive dysfunction and CKD severity, as measured by GFR. Seliger et al. [32] demonstrated

that the prevalence of dementia

in these individuals was 37%, in a 6-year follow-up. In addition,

in another study [33] it was observed that

elderly people with GFR lower than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 presented a

faster decline in cognition,

especially in memory domains. Our findings

lead to the understanding that the benefits of

Pilates permeate physical function, also collaborating to improve mental and cognitive aspects

in CKD. Similar results were

found in an extensive review of reviews with a sample of 128,119 individuals [34]. In this study, the practice

of physical activity, in different modalities, was able to reduce

mild to moderate

symptoms of depression, anxiety and psychological distress compared to usual care in all populations and specifically in greater magnitude in those with CKD and other

chronic diseases [34].

In this systematic review of the literature,

we identified that the practice

of Pilates can act directly on

the physical dysfunctions of CKD, thus contributing to the improvement

of QoL. However,

it is important to take into account

the specificity of the results

presented here to define the need

to associate Pilates with other interventions,

according to the individuality of the patient.

Limitations

The small number of

works and the heterogeneity in the QoL assessment methods are the main limitations of this systematic

review. These factors made it impossible to carry out the

meta-analysis, which does not allow us

to establish a causal reaction in our work. Moreover, the methodological quality of the

analyzed works also limits our

power of inferences. The increment of objective evaluation

such as functional tests, and the

type and location of vascular access for hemodialysis in future

studies are necessary to establish the

association between QoL and functional

capacity and safety in performing Pilates.

Conclusion

Our results point

out that the practice of physical

exercise with the Pilates method can favor the improvement

of the quality

of life in individuals with chronic kidney disease. More studies, with standardization of quality of

life assessment and association with functional and clinical parameters, are needed to better

elucidate these findings in the future.

Funding source

Nothing to

declare.

Conflict of

interest

We declare that we have

no conflicts of interest.

Authors' contribution

Research conception

and design: Soares LO; Obtaining

data: Soares LO, Silva WS, Mortari BR; Data analysis

and interpretation: Soares

LO, Silva WS, Mortari BR; Statistical analysis: Soares LO, Silva WS; Writing of the manuscript: Soares

LO, Silva WS, Mortari BR, Cordeiro ALL; Critical

review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Soares

LO, Silva WS, Mortari BR, Falleiros AM, Cordeiro ALL.

References

- Romão Junior JE. Chronic kidney disease: definition, epidemiology and classification. Braz J Nephrol.

2004;26(3suppl.1):1-3. doi: 10.1111/jch.14186 [Crossref]

- Heiwe S, Dahlgren MA. Living with chronic renal failure: coping with physical activity of daily living. Advances in Physiotherapy. 2004;6:147-57. doi: 10.1080/14038190410019540 [Crossref]

- Johansen KL. Exercise and chronic kidney disease: current recommendations. Sports Med. 2005;35:489-99. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200535060-00003 [Crossref]

- Flisinski M, Brymora A,

G Elminowska-Wenda, J Bogucka,

K Walasik, A Stefanska, et

al. Morphometric analysis of muscle fibre

types in rat locomotor and postural skeletal muscles in different stages of chronic

kidney disease. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;65:567-76.

- Marinho DF, Melo RDC, Sousa KEP, Oliveira FA, Vieira JNS, Antunes CSP et al. Functional capacity and quality of life in chronic kidney disease. Rev Pesqui Fisioter. 2020;10(2):212-19. doi: 10.5935/0101-2800.20150008 [Crossref]

- Fletcher BR, Damery S, Aiyegbusi OL, Anderson N, Calvert M, Cockwell P et al. Symptom burden and health-related quality of life in chronic kidney disease: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2022;19(4):e1003954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003954 [Crossref]

- Jesus NM, de Souza GF, Mendes-Rodrigues C, Almeida Neto OP, Rodrigues DDM, Cunha CM. Quality of life of individuals with chronic kidney disease on dialysis. Braz J Nephrol. 2019;41(3):364-74. doi: 10.1590/2175-8239-JBN-2018-0152 [Crossref]

- Ghiasi B, Sarokhani D, Dehkordi AH, Sayehmiri K, Heidari MH. Quality of Life of patients with chronic kidney disease in Iran: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24(1):104-111. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_146_17 [Crossref]

- Cheema E, Alhomoud FK, Kinsara ASA, Alsiddik J, Barnawi MH, Al-Muwallad MA, et al. The impact of pharmacists-led medicines reconciliation on healthcare outcomes in secondary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, PLoS One. 2018;13(3)e0193510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193510 [Crossref]

- Duff WRD, Andrushko JW, Renshaw DW, Chilibeck PD, Farthing JP, Danielson J, et al. Impact of Pilates exercise in multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Int J MS Care. 2018;20(2):92-100. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2017-066 [Crossref]

- Caldwell K, Harrison, M., Adams, M., Triplett, N.T., 2009. Effect of Pilates and taiji quan training on self-efficacy, sleep quality, mood, and physical performance of college students. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2009;13,155e163. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2007.12.001 [Crossref]

- Natour J, Cazotti Lde A, Ribeiro LH, Baptista AS, Jones A. Pilates improves pain, function and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29(1):59-68. doi: 10.1177/0269215514538981 [Crossref]

- Vancini RL, Rayes ABR, Lira CAB, Sarro KJ, Andrade MS. Pilates and aerobic training improve levels of depression, anxiety and quality of life in overweight and obese individuals. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2017;75(12):850-57. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X20170149 [Crossref]

- Denham-Jones L, Gaskell L, Spence N, Pigott T. A systematic review of the effectiveness of Pilates on pain, disability, physical function, and quality of life in older adults with chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Musculoskeletal Care. 2022;20(1):10-30. doi: 10.1002/msc.1563 [Crossref]

- Maher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [Crossref]

- Haynes BR. Formulating research questions. J Clin Epidemiol.

2006;59(9):881-6.

- Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Moseley

AM, Elkins M. Reliability of the PEDro

scale for rating quality of randomized controlled

trials. Phys Ther 2003; 83:713-21.

- Kheirkhah D, Mirsane A, Ajorpaz NM, Rezaei M. Effects of Pilates exercise on quality of life of patients on hemodialysis. Crit Care Nurs J. 2016;9(3):e6981. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.05.012 [Crossref]

- Rahimimoghadam Z, Rahemi Z, Mirbagher Ajorpaz N, Sadat Z. Effects of Pilates exercise on general health of hemodialysis patients. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2017;21(1):86-92. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.05.012 [Crossref]

- Rahimimoghadam Z, Rahemi Z, Sadat Z, Mirbagher Ajorpaz N. Pilates exercises and quality of life of patients with chronic kidney disease. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019;34:35-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.10.017 [Crossref]

- Denham-Jones L, Gaskell L, Spence N, Pigott T. A systematic review of the effectiveness of Pilates on pain, disability, physical function, and quality of life in older adults with chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Musculoskeletal Care. 2022;20(1):10-30. doi: 10.1002/msc.1563 [Crossref]

- Espíndula RC, Nadas GB, Rosa MID, Foster C, Araújo FC, Grande AJ. Pilates for breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 1992;63(11):1006-12. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.63.11.1006 [Crossref]

- Anand S, Johansen KL, Kurella Tamura M. Aging and chronic kidney disease: the impact on physical function and cognition. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(3):315-22. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt109 [Crossref]

- Shlipak MG, Stehman-Breen C, Fried LF, Song X, Siscovick D, Fried LP, Psaty BM, Newman AB. The presence of frailty in elderly persons with chronic renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(5):861-7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.12.049 [Crossref]

- Odden MC, Whooley MA, Shlipak MG. Association of chronic kidney disease and anemia with physical capacity: the heart and soul study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(11):2908–15. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000143743.78092.E3 [Crossref]

- Guclu-Gunduz A, Citaker S, Irkec C, Nazliel B, Batur-Caglaya HZ. The effects of Pilates on balance, mobility and strength in patients with multiple sclerosis. NeuroRehabilitation. 2014;34(2):337–42. doi: 10.3233/NRE-130957 [Crossref]

- Cruz-Ferreira A, Fernandes J, Laranjo L, Bernardo LM, Silva A. A systematic review of the effects of Pilates method of exercise in healthy people. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(12):2071–81. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.06.018 [Crossref]

- Oliveira FC, Almeida FA, Gorges B. Effects of Pilates method in elderly people: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2015;19(3):500-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.03.003 [Crossref]

- Souza C, Krüger RL, Schmit EFD, Wagner Neto ES, Reischak-Oliveira Á, de Sá CKC, Loss JF. Cardiorespiratory adaptation to Pilates training. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2021;92(3):453-59. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2020.1749222 [Crossref]

- Tinoco-Fernández M, Jiménez-Martín M, Sánchez-Caravaca MA, Fernández-Pérez AM, Ramírez-Rodrigo J, Villaverde-Gutiérrez C. The Pilates method and cardiorespiratory adaptation to training. Res Sports Med. 2016;24(3):281-6. doi: 10.1080/15438627.2016.1202829 [Crossref]

- Sarmento LA, Pinto JS, da Silva AP, Cabral CM, Chiavegato LD. Effect of conventional physical therapy and Pilates in functionality, respiratory muscle strength and ability to exercise in hospitalized chronic renal patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(4):508-20. doi: 10.1177/0269215516648752 [Crossref]

- Seliger SL, Siscovick DS, Stehman-Breen CO, et al. Moderate renal impairment and risk of dementia among older adults: The Cardiovascular Health Cognition Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(7):1904–11. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000131529.60019.fa [Crossref]

- Buchman AS, Tanne D, Boyle PA, Shah RC, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. Kidney function is associated with the rate of cognitive decline in the elderly. Neurology. 2009;73(12):920–27. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b72629 [Crossref]

- Singh B, Olds T, Curtis R, Dumuid D, Virgara R, Watson A, et al. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: an overview of systematic reviews. Br J Sports Med. 2023. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-106195 [Crossref]