Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc. 2023;22:e225468

doi: 10.33233/rbfex.v22i1.5468

REVIEW

Protocol to reduce the risk of unintentional doping caused by dietary supplements ingestion

Protocolo de redução de risco de doping não intencional causado por consumo de suplementos alimentares

Renata

Rebello Mendes1, João Rafael Santos Prado1

1Universidade Federal de Sergipe,

Aracaju, SE, Brazil

Received: May 5, 2023; Accepted: June 22, 2023.

Correspondence: Renata Rebello

Mendes, remendes@academico.ufs.br

How to cite

Mendes RR, Prado JRS. Unintentional doping:

A proposal for a risk reduction protocol based on an analytical review of the

risks and good practices of dietary supplementation in elite athletes. Rev Bras

Fisiol Exerc. 2023;22:e225468. doi: 10.33233/rbfex.v22i1.5468

Abstract

Introduction: Dietary

supplements have been considered the main cause of unintentional doping among

athletes; however, the prevalence of supplement use by elite athletes is almost

100%, and awareness of the risk of unintentional doping does not seem to be

effective. The literature has pointed out some possible factors related to the

poor quality of products available on the market; however, it does not propose

any protocol that objectively guides health professionals and athletes in terms

of reducing the risk of doping and damage to health caused by supplements

contaminated with prohibited substances not listed on the label. Objective:

To propose a protocol to reduce the risk of unintentional doping, based on a

narrative review of studies that have discussed regulatory factors related to

dietary supplements, prevalence of contamination of supplements, their main

contaminants, possible adverse effects on human health, awareness of athletes

about the indications for supplement use and the risks of unintentional doping.

Methods: Narrative review and document analysis on the websites of

international agencies related to anti-doping policy, such as the World

Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the Brazilian Authority for Doping Control

(ABCD). Results: A six-step protocol was developed, which proposes methods

potentially capable of reducing the risk of unintentional doping. Conclusion:

This instrument could be highly relevant in sports, especially among elite

athletes; however, without excluding the importance for any consumer of this

type of product, since high prevalence of contamination of food supplements and

consumption of this product were identified, as well as insufficient awareness

on the part of its consumers.

Keywords: dietary supplements; doping in

sports; athletic performance; security measures.

Resumo

Introdução: A suplementação alimentar tem sido

considerada a principal causa de doping não intencional entre atletas; no

entanto, a prevalência de consumo de suplementos por atletas de elite é próxima

a 100%, e a conscientização sobre o risco de doping não intencional não parece

ser efetiva. A literatura científica tem apontado alguns possíveis fatores

relacionados à má qualidade dos produtos disponíveis no mercado; entretanto,

não propõe qualquer protocolo que oriente, objetivamente, profissionais da área

da saúde e atletas quanto à redução de risco doping e danos à saúde causados

por suplementos contaminados com substâncias proibidas não listadas no rótulo. Objetivo:

Propor um protocolo de redução de risco de doping não intencional, a partir de

uma revisão narrativa sobre estudos que tenham discutido os fatores

regulatórios relacionados aos suplementos alimentares, prevalência de

contaminação de suplementos, seus principais contaminantes, possíveis efeitos

adversos à saúde humana, conscientização de atletas sobre as indicações para

uso de suplementos e os riscos de doping não intencional. Métodos:

Revisão narrativa e análise documental nos sites das agências internacionais

relacionadas à política antidopagem, como a Agência Mundial Antidopagem (WADA)

e a Autoridade Brasileira de Controle de Dopagem (ABCD). Resultados: Foi

elaborado um protocolo de seis passos, que propõe métodos potencialmente

capazes de reduzir o risco de doping não intencional. Conclusão: Esse

instrumento poderia ser de elevada relevância no âmbito esportivo,

especialmente entre atletas de elite, no entanto, sem excluir a importância

para outros consumidores desse tipo de produto, uma vez que foram identificadas

elevadas prevalências de contaminação de suplementos alimentares e de consumo desse

produto, bem como insuficiente grau de conscientização por parte de seus

consumidores.

Palavras-chave: suplementos nutricionais; doping nos

esportes; desempenho atlético; medidas de segurança.

Introduction

Elite athletes are constantly

submitted to challenges in which sports performance improvement stands out as a

central objective, either during training sessions or competitive events [1].

In this scenario, any evolution in performance, even if minimal, can be enough

to significantly influence an athlete’s result in a championship [2].

Among the factors capable of

promoting performance improvement in athletes, nutritional status stands out,

although some international positions mention that most of an athlete’s

nutritional needs can be achieved through simple food adjustments in their

routine [3]. Stellingwerff et al. [4] clarify

that some athletes may face difficulties making such adjustments viable.

In this sense, the two main types

of difficulties faced by athletes can be summarized as: a) limitations in the

consumption of adequate amounts of food, as athletes often mention not eating

enough due to gastrointestinal discomfort during training sessions or

competitions or because they experience reduced appetite and even changes in their

eating routine, due to constant international travel [4]; b) supply limitations

of specific ergogenic compounds, such as creatine, beta-alanine, caffeine,

nitrate, and sodium bicarbonate, considered safe and effective by the

International Olympic Committee (IOC), provided they are consumed in adequate

doses, which are not reached exclusively through food [5].

Faced with the difficulties of

meeting nutritional needs and specific ergogenic effects exclusively through

food, the of dietary supplements has been increasing among elite athletes,

ranging from 78 to 100% of this population, depending on the modality studied

[6,7]. However, it is essential to clarify that not all athletes face such

difficulties, which highlights the importance of individual nutritional

assessment [8].

For those athletes who need food

supplementation to achieve specific ergogenic effects and/or to maintain an

adequate nutritional status; and consequently prevent negative outcomes

resulting from malnutrition, such as overtraining syndrome and relative energy

deficiency in sport (REDS), it is necessary to clarify that this strategy is

considered the greatest risk factor for unintentional doping [9], being

responsible for approximately 6.4 and 8.9% of all adverse analytical findings

(positive doping) [10].

Doping has been defined as the

presence of prohibited substances and/or their metabolites in blood or urine

samples, and it is considered an unsportsmanlike crime, with the consequences

of losing titles, banning participation in competitions, compromising

reputation, and damage to health [11].

According to the principle of

“Strict Liability” provided for in Art. 14, paragraph III of the World

Anti-Doping Code [12], “it is not necessary that intent, fault, negligence or

knowing Use on the Athlete’s part be demonstrated in order to establish an

anti-doping violation”. In this way, when consuming a poor-quality food

supplement contaminated with substances prohibited by the World Anti-Doping

Agency (WADA) without any identification on the label, the athlete obtains

performance advantages in relation to his opponents, even if unintentionally.

Therefore, when presenting adverse analytical findings, they may suffer the

sanctions provided for this type of crime, as well as be exposed to the risk of

developing potential adverse health effects caused by prohibited substances.

The scientific literature has

pointed out some possible factors related to the poor quality of products

available on the market [11]. However, it does not propose any protocol that

objectively guides health professionals and athletes in reducing the risk of

doping and health damage caused by supplements contaminated with prohibited

substances not listed on the label.

Therefore, the first objective of

the present study was to carry out a narrative review of studies that have

discussed regulatory factors related to dietary supplements, the prevalence of

contamination of supplements, their main contaminants, possible adverse effects

on human health, awareness of athletes about the indications for supplements

use and the risks of unintentional doping. Based on this narrative review, the

second objective of the present study was to propose a protocol to reduce the

risk of unintentional doping.

Methods

The study consisted of a narrative

review and document analysis, in which conclusions culminated in a protocol

proposition to reduce the risk of unintentional doping.

The narrative review was carried

out through scientific articles indexed in the databases: PubMed, Google

Scholar, Science Direct and Web of Science, and Portal de Periódicos

CAPES, without language restrictions, through the terms “dietary supplements”,

“banned substances”, “contamination”, “cross-contamination”, “doping”,

“unintentional doping”, “involuntary doping”. Other relevant sources were found

in the references of related articles. No additional filters have been added,

and the last search was performed in February 2023.

For the document analysis, the

websites of governmental organizations and international agencies related to

the anti-doping policy were consulted, such as the World Anti-Doping Agency

(WADA) and the Brazilian Doping Control Authority (ABCD), and the last search

was carried out in February 2023.

Results and discussion

Regulatory factors related to dietary supplements

Unlike the rigid processes that

regulate the registration and marketing of a new drug, in much of the world,

the quality of food supplements is not tested before these products reach the

market [11].

In Europe and the United States

(USA), the producers themselves are responsible for “guaranteeing” the safety

of dietary supplements, with no need for proof before the product reaches the

market, which increases the risk of marketing poor-quality products [13].

In the US, the dietary supplement

industry is overseen by two federal agencies, the FDA and the Federal Trade

Commission (FTC), in which the first is in charge of the safety and proper labeling

of products, and the second of their advertising and promotional claims. In the

case of the FDA, its action is governed by the Dietary Supplement Health and

Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994, which classified these products as food and,

therefore, exempted them from proving their safety before being marketed [14].

In this country, drugs are considered unsafe until evidence shows otherwise;

food supplements are considered safe until proven they are not [15].

Thus, since manufacturers are not

required to submit safety information before marketing dietary supplements in

the US, the FDA depends on adverse event reports, product sampling, and

information from the scientific literature as evidence of risk. Consequently,

for an inappropriate product to be withdrawn from circulation in the US, it

must first have documented victims and be brought to the attention of health

authorities [15].

It is noteworthy that US supplement

manufacturers must comply with Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) requirements,

which state that they "must establish - for each component and the

finished dietary supplement - specifications as to identity, purity, strength,

composition, and limits of contaminants, to assure its quality”. However, the

US GMP guidelines do not specify which tests and methods must be adopted, which

allows manufacturers to decide which methodologies they will base their quality

controls on. As a consequence, problems such as the presence of impurities,

microorganisms, toxins, and toxic elements such as lead, mercury, arsenic, and

cadmium in the products may occur, as well as the poor characterization and

replacement of declared components by cheaper alternatives, of lower quality

and even the inclusion, not informed on the label, of active ingredients prohibited

by WADA.

In Brazil, the regulation of the

dietary supplements sector is similar to the American and European ones, being

governed by the Resolution of the Collegiate Board (RDC) number 243 of July 26,

2018, of the National Health Regulatory Agency (Anvisa),

which provides for “the requirements for the composition, quality, safety, and

labeling of dietary supplements and for updating the lists of nutrients,

bioactive substances, enzymes, and probiotics, use limits, claims and

complementary labeling of these products” [16], plus the lists of permitted and

prohibited ingredients of Normative Instruction number 28 also of July 26,

2018, later modified by Normative Instruction number 76 of November 5, 2020.

As in the US, Brazil also regulates

dietary supplements more as food than as medicine, which translates into milder

and simpler standards and requirements for their registration and marketing,

and a lower degree of inspection. Unlike what happens in the USA; however,

Brazilian manufacturers must previously submit to Anvisa

information on the safety and efficacy of their products, which may include

scientific evidence such as clinical trials, endorsement by health authorities

or recognized regulatory bodies in other countries; in addition to of

pharmacopeias or other specific codes for the sector in Brazil or abroad [14].

In Brazil, until 2018, there was no

legal definition for dietary supplements. At that time, most of the products

used as dietary supplements were classified into different regulatory

categories: (I) Food for athletes; (II) Vitamin and/or mineral supplements;

(III) New foods and/or new ingredients; (IV) Foods with functional and/or

health properties; (V) Specific drugs; and (VI) Herbal Medicines. However, in

recent years, Anvisa has promoted a series of

debates, which led to RDC Anvisa nº 243/2018, which

defines the health requirements of dietary supplements and is characterized as

a regulatory framework in the country. Anvisa also established

food additives and technology adjuvants authorized for use in food supplements

through RDC Anvisa nº 239, of July 26, 2018 [17] and

published Normative Instruction nº 76, which provides for the updating of lists

of constituents, use limits, claims and complementary labeling of food

supplements; including minimum and maximum limits of nutrients, bioactive

substances, enzymes, and probiotics that may be contained in food supplements,

based on the daily recommendation for consumption of the product for certain

population groups indicated by the manufacturer [18].

RDC nº 243 [16] deals with

regulating the requirements for composition, quality, safety, and labeling of

food supplements, both for the industrial environment of large-scale production

and commercialization and for compounding pharmacies. Among several standards

established in this Resolution, the need to identify ingredients on the product

label stands out. More specifically, article 7 defines that “substances

considered as doping by the World Anti-Doping Agency are not allowed in the

composition of food supplements” (Table I). However, except for products

containing enzymes or probiotics, it is not mandatory to carry out analyzes of

food supplements before they are placed on the market, and the manufacturer is

solely responsible for declaring that he complies with the rules and

communicating the start of manufacture or importation of the product to the

local health surveillance agency. Added to this is the scarcity of official

methodologies in Brazil for carrying out this type of analysis, making the

quality and safety of these products questionable.

Table I - World anti-doping agency list

of prohibited substances and methods for the year 2023

Source: WADA - World Anti-Doping Agency

[19]

Cross-contamination is usually

attributed to errors in production in situations in which supplements and other

products containing substances prohibited by WADA are manufactured on the same

production line; in this case, containers or benches previously used in

handling prohibited substances are improperly cleaned and then reused for the

transport or storage of raw materials and food supplements, culminating in

contamination. There is also the hypothesis that the inclusion of the prohibited

substances in dietary supplements is intentional to increase the effectiveness

of the products and build consumer loyalty [20]. Additionally, the Brazilian

Doping Control Authority (ABCD) warns that, for the most part, contaminated

products are those often listed as possibly capable of reducing body weight and

promoting increased muscle anabolism [21], which corroborates with the

hypothesis of intentional contamination.

Therefore, as

the food supplements industry continues to grow and athletes continue to

consume them, the review and modernization of the regulation of this industry

are extremely necessary to prevent both acute and chronic damage to health, as

well as unintentional doping [11]. However, while the legislation is not

changed, the need to create mechanisms to reduce the risk of unintentional

doping is clear.

Prevalence of contamination of food supplements, their

main contaminants and possible adverse effects on human health

Passive exposure to prohibited

substances, caused by the consumption of dietary supplements, in addition to

causing damage to health, also makes elite athletes susceptible to

unintentional doping [22,23].

In a study by Kozhuharov,

Ivanov, and Ivanova [11], 50 studies were gathered and published between 1996

and 2021, in which 875 dietary supplements were analyzed as possible sources of

unintentional doping. The dietary supplements studied came from practically all

parts of the world, predominantly from the USA, Holland, United Kingdom, Italy,

and Germany, followed by products manufactured in China and Southeast Asia. The

authors found that of all the supplements analyzed, about 28% had a high risk

of unintentional doping due to the substances present but not declared on the

label.

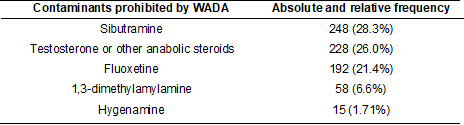

Among these substances, the most

common was sibutramine in 248 contaminated food supplements (28.34%), followed

by testosterone and other anabolic steroids in 228 products (26.06%),

fluoxetine in 192 products (21.37%), 1,3-dimethylamylamine (DMAA) in 58

products (6.62%) and hygenamine in 15 (1.71%) of the

875 food supplements analyzed. Other substances such as diuretics and Selective

Androgen Receptor Modulators (SARMs) not declared on the labels and prohibited

by WADA were also identified in the products, but to a lesser extent (Table II)

[11].

Table II - Main contaminants found in

dietary supplements, and their frequency, not identified on the label

Source: Adapted from Kozhuharov, Ivanov, and Ivanova [11].

Food supplements, in general, are

used chronically, some even very frequently throughout the day. And if they are

contaminated with pharmacologically active substances, they can expose

consumers to serious side effects due to the accumulation of prohibited

substances without the slightest control of the ingested dose. Therefore, the

unexpected consumption of adulterated supplements can cause adverse effects

such as allergies, and cardiovascular, liver, and kidney problems, among

others, depending on the level of adulteration and the consumer's tolerance to

such substances [24].

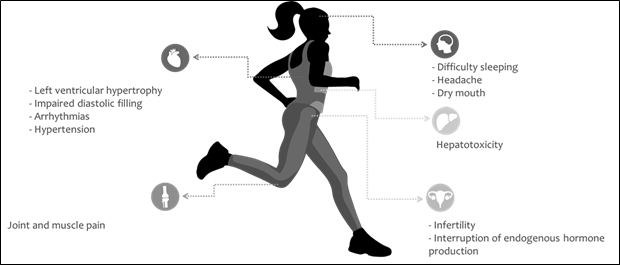

According to Kozhuharov,

Ivanov, and Ivanova [11], the most recurrent substance in dietary supplements

as a contaminant was sibutramine. This substance poses serious health risks

both for elite athletes and for other individuals. Its ingestion can cause

several side effects, such as increased blood pressure, arrhythmias, dry mouth,

difficulty sleeping, headache, or joint and muscle pain [25,26,27].

Another type of substance that

stood out in the study by Kozhuharov, Ivanov, and

Ivanova [11] as a contaminant of food supplements was the category of anabolic

steroids; its adverse effects are correlated with prolonged use, which may lead

to interruption of the endogenous production of these hormones, as well as

infertility and gynecomastia. Additionally, they are associated with

cardiovascular side effects such as left ventricular hypertrophy, impaired

diastolic filling, hypertension, thrombosis, and hepatotoxicity [28,29,30].

Source: Florentin et al. [25];

James et al. [26]; Scheen [27]; Torrisi et al. [28]; Karila et

al. [29]; Ivanova et al. [30]

Figure 1 - Major adverse health effects

caused by contaminants predominantly found in dietary supplements, such as

sibutramine, testosterone or other anabolic steroids, 1,3-Dimethylamylamine,

and hygenamine

As previously mentioned, the study

by Kozhuharov, Ivanov, and Ivanova [11] analyzed 50

studies published between 1996 and June 21, 2021, and found a prevalence of 28%

of contamination among food supplements. After this period, in our searches,

using the same descriptors and research platforms, we found four more studies

[31,32,33,34] whose objective was to evaluate the contamination of sports food

supplements.

Duiven et

al. [31] evaluated the prevalence of doping substances in a variety of

sports food supplements available in Dutch online stores. A total of 66 sports

supplements - identified by the study authors as "potentially high-risk

products" as their advertising claimed to modulate hormone regulation,

stimulate muscle mass gain, enhance fat loss, and/or increase energy - were

selected from 21 different brands and purchased in 17 virtual stores. All

products were analyzed for the presence of prohibited substances by a company

with extensive experience in anti-doping control. A total of 25 of the 66

products (38%) contained substances prohibited by the WADA, not declared on the

label, which included high levels of the stimulants oxylophrine,

β-methylphenethylamine and N,β-dimethylphenethylamine,

the stimulant 4-methylhexan-2-amine (methylhexaneamine,

1,3-dimethylamylamine, DMAA), the anabolic steroids boldenone

(1,4-androstadiene-3,17-dione) and 5-androstene-3β,17α-diol (17α-AED),

the beta-2 agonist higenamine and the beta-blocker

bisoprolol. The authors concluded that the ingestion of some products identified

in this study, in the concentrations found, could represent a significant risk

of unintentional doping violations and to consumers' health.

Leaney et

al. [32] carried out a study on the consumption of hygenamine

through products made from beetroot, currently evidenced as an ergogenic

strategy because it is a source of nitrate. To investigate this relationship,

concentrated beetroot beverages were consumed by six individuals, and this

compound was quantified in the urine. Hygenamine was

confirmed to be present in the majority of beet-derived foods and supplements

tested in this study, with experimental evidence that it can arise in beet

extracts upon heating. The results of this study demonstrate the first evidence

of a relationship between beetroot and hygenamine, a

substance prohibited by WADA.

It is noteworthy that, although

free hygenamine was detected in the urine of all

individuals tested in the study by Leaney et al.

[32], its concentration was significantly low, representing about 1% of the

acceptable limit described in the current WADA report. However, although the

risk of inadvertent doping violation by consuming the products investigated in

this study is low, beetroot as a source of hygenamine

should be considered by athletes, especially those who consume amounts higher

than those recommended by the manufacturers.

In the third study found in our

searches, after the publication of the systematic review by Kozhuharov,

Ivanov, and Ivanova [11], Zhang et al. [33] proposed a new analytical

method for the detection of anabolic steroids, also prohibited by WADA, in

samples of food supplements. The method was considered sensitive and accurate,

and when analyzing 300 liquid and solid food supplements, it detected a

positive sample for testosterone and three suspected drugs

(4-hydroxyandrostenedione, DHEA, and 6-Br androstenedione) in three food

supplements purchased on the internet.

Finally, in the last study found in

our searches, after the publication of the systematic review by Kozhuharov, Ivanov, and Ivanova [11], Rodriguez-Lopez et

al. [34] analyzed 52 “sports supplements” made of protein available in

physical and online stores in Spain with several objectives, among them, to

identify possible contamination with substances prohibited by the WADA. No

ingredients banned by WADA were found, except for colostrum in one of the

supplements, and consumption of colostrum is currently discouraged by WADA, as

it may contain growth factors (IGF-1), among others, which are prohibited and

can lead to doping.

When analyzing data from Zhang et

al. [33] and Rodriguez-Lopez et al. [34], it is possible to observe

a prevalence of contamination (1.33% and zero, respectively) lower than the 38%

reported by Duiven et al. [31] and the 28% mentioned

in the review by Kozhuharov, Ivanov, and Ivanova

[11]. However, in the first case, only one type of prohibited substance

(steroids) was evaluated, while in the second case, only protein supplements

marketed in a single country. While in the studies by Duiven

et al. [31] and Kozhuharov, Ivanov, and

Ivanova [11], there was an investigation of numerous types of prohibited

substances, specifically, in the case of Kozhuharov,

Ivanov, and Ivanova [11], it is a systematic review with meta-analysis, which

brought together supplements from all over the world, which reinforces the need

for extreme vigilance concerning the consumption of food supplements by

athletes.

Athletes' awareness of dietary supplements and the

risk of unintentional doping

The most cited motivations for

dietary supplements use by athletes around the world have been improvements in

performance, health, and recovery. Additionally, women are more likely to

consume supplements for health reasons, while men more often report using them

to enhance sports performance [6,35]. However, according to Walpurgis et al.

[20], most athletes using dietary supplements are not aware of the consequences

of consuming contaminated dietary supplements, such as unpredictable health

risks and adverse analytical discovery in routine doping controls.

Studies have found that athletes'

main sources of information on the subject tend to be of low quality, as they

mostly come from their coaches, team partners, friends, or even family members

[35,36,37]. According to Dodge [38], consumers of dietary supplements mistakenly

believe that if dietary supplements are approved by the government, then they

are tested for safety and efficacy, as well as have their content analyzed in

the laboratory, and manufacturers are obliged to disclose adverse effects on

consumers. However, this is not observed in practice since the laws of several

countries do not require such procedures.

A study by Braun et al. [39]

found that only 36% of the participating athletes knew that food supplements

could have some type of contaminant. Following by Torres-McGehee et al.

[40], in which only 9% of 400 North American athletes had adequate knowledge

about sports nutrition, including supplementation. Another study with college

athletes showed that 86% were unaware that food supplements could have

potential adverse effects [37]. In addition to these, a study carried out with

Australian athletes on the same subject showed that 62% of respondents did not

know the active ingredient(s) of the supplement(s) they consumed, 57% did not

know about the possible adverse effects, 54% were unaware of the mechanism of

action, and 52% were unaware of the recommended dose [41].

Chan et al. [42] evaluated

410 young athletes (17.7 years old ± 3.9), Australian, from regional, national,

and international levels, from modalities such as Athletics, Badminton,

Swimming, Gymnastics, Swimming, Triathlon, Basketball, Cricket, Football,

Rugby, hockey and water polo. Such athletes received a lollipop free of charge

while waiting for the completion of a questionnaire. Among the various findings

of the study, it was observed that only 40.6% refused to eat an unknown food

given to them and that among all those who consumed the product, only 16.1%

read the list of ingredients before making it. This study suggests that young

athletes had a low level of concern about exposing themselves to new food

products and the possible risks of unintentional doping.

Some countries, such as Germany,

France, the United Kingdom, Austria, and Holland, have databases available for

athletes, which catalog dietary supplements tested for ingredients [20].

Specifically, in Holland in 2003, the Dutch Safeguards System for Dietary

Supplements in Elite Sport, known as NZVT, was created [43]. Thus, Wardenaar et al. [44] tested the knowledge and

attitudes of 601 Dutch athletes with Olympic and non-Olympic status towards the

NZVT system. The authors showed that, although the majority (68%) of athletes

were aware that dietary supplements can lead to an adverse analytical finding,

and 87.8% of these athletes considered fraud due to incomplete labeling

unacceptable, there is still a reasonable portion of these athletes (32%) who

are unaware of such risks. Of the athletes who were aware of the NZVT system,

those with Olympic status reported using it more frequently than non-Olympic

athletes (81.7% vs. 50.0%, p < 0.001). Additionally, women were more

familiar with and used the system more frequently when compared to men. In

conclusion, the authors report that although doping warnings and regulations

have been in place, considering the risk of unintentional use of doping for

more than two decades, knowledge of the Olympic and non-Olympic status of

high-level athletes still needs to be improved.

The studies cited above show that

even athletes from countries with programs or systems that guide the purchase

of safe products are still insufficiently aware of the risk of unintentional

doping caused by the consumption of contaminated food supplements. According to

our searches, there is no robust investigation on the subject in Brazil, but

considering that in this country there is no governmental system to protect

athletes in this sense, it is believed that the level of awareness is even lower,

which raises the question of the need for educational programs in this regard

and the proposition of risk reduction protocols.

Proposal for a Protocol to reduce the risk of

unintentional doping through dietary supplements

Considering that the risk of

unaware athletes consuming dietary supplements contaminated with substances

prohibited by WADA is high, but also considering that the use of these products

may be indispensable in certain elite sports scenarios and that changes in

regulatory factors are unlikely to occur in the short term, the proposal of a

risk reduction protocol becomes fundamental. In this way, our proposal will be

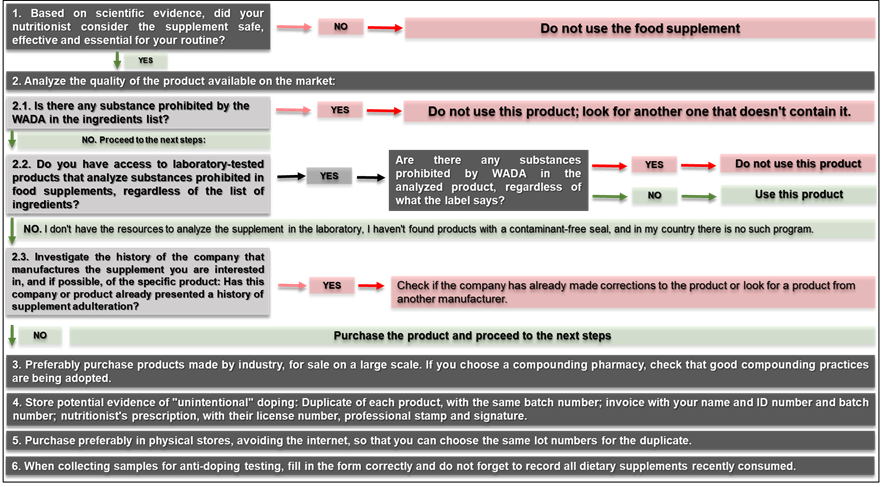

exposed in 6 steps:

1st Step: Consume only food supplements

that are strictly necessary and that present scientific evidence of efficacy

and safety.

Few commercially available products

claiming ergogenic benefits are supported by solid evidence. Research

methodologies on the effectiveness of sports supplements are often limited by

small sample sizes, the inclusion of untrained individuals, low representation

of specific subpopulations of athletes (women, older athletes, athletes with

disabilities, etc.), performance tests that are unreliable or irrelevant, poor

control of confounding variables, by not including control of the athletes'

diet during the study or by not considering the interaction with other

supplements [45,46].

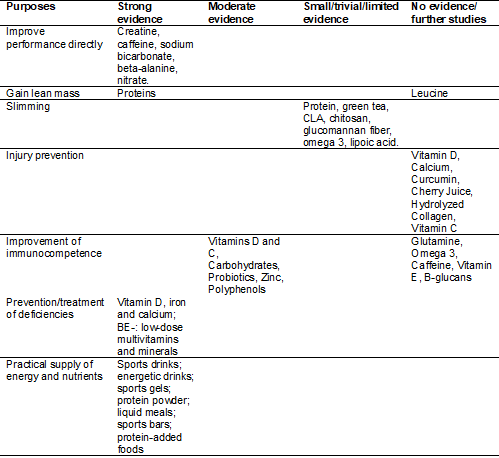

The International Olympic

Committee, in a position released recently [5], categorized food supplements

according to the purpose of use and the degree of evidence regarding safety and

efficacy. Following these criteria, the following categories emerged:

supplements whose purposes are: (a) Practically providing energy and nutrients,

(b) Preventing and/or treating nutritional deficiencies, (c) Promoting muscle

mass gain, (d) Promoting weight loss, (e) Promote performance improvement

indirectly, through injury prevention and immunity improvement, (f) Promote

performance improvement directly.

According to Table III, in the

category “supplements whose purpose is to directly promote performance

improvement”, for example, there is evidence that only five dietary supplements

- creatine, sodium bicarbonate, beta-alanine, caffeine, and nitrate - could

promote gains in performance margins, as long as they are used in specific

scenarios [5]. Thus, in practice, the athlete should stick to just such

possibilities, also considering the guidance of a nutritionist to assess the

feasibility of use according to the specific scenario, such as training

periodization, the specificity of each sport modality, and the biological

individuality of the athlete.

Table III - Categorization of food

supplements according to purpose of use and degree of evidence regarding safety

and efficacy

Source: Adapted from Maughan et

al. [5]

In addition to the positions

published by specific entities such as IOC [5], ISSN [3], and ACSM [47], the

nutritionist responsible for prescribing dietary supplements can use other

types of studies for decision-making. In this case, the professional must

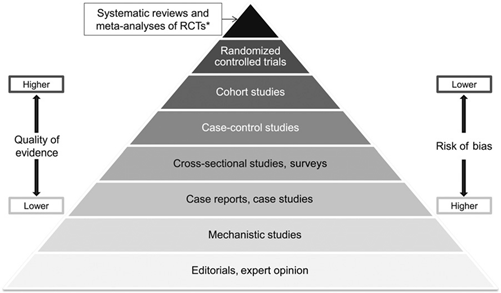

define his conduct based on scientific evidence, as suggested in Figure 2, understanding

that the highest level of reliability has been found in systematic review

studies with or without meta-analysis.

*RCTs = Randomized clinical trials.

Source: Pereira and Veiga [48]

Figure 2 - Hierarchy of evidence used to

establish good health practices

Finally, if there is still no

systematic review with meta-analysis available for a given dietary supplement

and for the desired population, clinical trials can be useful in

decision-making, as long as they are interpreted critically, considering

criteria such as sample type, type of performance testing, study design,

supplement quality, study funding, and conflict of interest, among others, as

discussed by Porrini and Del Bo [49].

Thus, the nutritionist responsible

for prescribing dietary supplements must be able to interpret such studies,

base their conduct on scientific evidence, and guide athletes to use only what

is strictly necessary.

2nd step: Analyze the quality of the

product available on the market

Evaluate ingredient list

The first type of analysis refers

to something that precedes unintentional doping; that is, at first, the athlete

must be aware of the fact that it is his responsibility to analyze all the

compounds present in the list of ingredients, even though the marketing is more

directed to only one ingredient. In this case, if the prohibited substance is

described in the list of ingredients, it will no longer be characterized as

unintentional doping.

Analyze in the laboratory the substances present in

the food supplement, regardless of not being present in the list of ingredients

Considering that about 28% to 38%

of the products available on the market contain substances prohibited by WADA,

without these being described in the list of ingredients, step 2.1. is

essential, but not enough. To ensure that the product is free of contaminants,

it would be necessary to send a sample of it for laboratory analysis [11], and

if the result points to the presence of a contaminant, the athlete should

discard it and look for another option on the market.

However, such procedures are often

significantly costly for the athlete. Analyzing each product reduces the speed

of the process and can represent an unfeasible cost for most athletes. Thus, to

reduce such obstacles, there are two distinct initiatives, but still not very

effective in global terms: a) companies that sell food supplements tested in

batches (batch-tested) and certify such products, including seals on the

packaging, so that the consumer can identify it. However, they are rare on the

market and therefore difficult to access; b) Government programs aimed at

analyzing supplements and disclosing to athletes a list of tested and approved

products and their respective batches. However, according to our searches so

far, only five countries have this type of program: Germany, the United

Kingdom, France, Holland, and Austria [11].

It is important to point out that

each new batch of food supplement produced by the same company must be tested

again since it was probably handled at different times and perhaps under

different circumstances.

Investigate the history of the manufacturing company

In the impossibility of performing

analysis of a dietary supplement in the laboratory, either on the athlete's

initiative, by laboratories that perform analysis and disclose the seal on the

product label, or by governmental initiatives, Kozhuharov,

Ivanov, and Ivanova [11] suggest that, if the use of the product is crucial for

the health and performance of the athlete, before acquiring it, the athlete must

investigate the history of the manufacturing company, in search of possible

previous accusations. In this same line of reasoning, it is common for elite

athletes from the same team to share experiences, the most experienced ones report to the most novices the brands that they have

been using for years and never generated adverse analytical findings in the

constant anti-doping controls to which they are submitted. The fact that a

company has never been denounced or caught in cases of contamination does not

prevent it from committing possible fraud in the future; however, according to Kozhuharov, Ivanov, and Ivanova [11], it is a reasoning of

reduction of probabilities. And for that reason, in parallel with this strategy

(step 2.3 of our protocol), more preventive measures should be taken, as

described in the following steps.

3rd step: Acquisition of dietary

supplements preferably produced in large-scale industry

The risks of contamination in

dietary supplements with prohibited substances are real; both in products

produced in industry, on a large scale, and in those manipulated in pharmacies.

However, according to ABCD [21], there is the possibility that part of the

compounding pharmacies does not strictly and consistently follow the criteria

required of manufacturers of industrialized products sold on a large scale, and

for this reason, they would represent a greater risk for consumers.

Additionally, Judkins, Teale, and Hall [50] suggest that some pharmacies that

handle medicines and dietary supplements may use contaminated or low-quality

raw materials, and work with unreliable substances, creating unsafe mixtures

with ingredients that have not yet been tested in humans [21].

However, our searches found that

scientific studies have been dedicated to assessing the presence of prohibited

substances in supplements produced on a large scale without necessarily

comparing their contamination rates with products handled in pharmacies

[51,52,53,54,55,56]. Therefore, given this scientific gap, it is not possible to state that

supplements produced on a large scale are less susceptible to contamination

than those manipulated in pharmacies.

While this gap is not filled

through new scientific evidence, in compliance with the ABCD and the document

still in force [21], our unintentional doping risk reduction protocol will

adopt the proviso that the preferential acquisition must be of products

produced in industry, without excluding, however, the option of products

manipulated in pharmacy. Additionally, if the athlete decides to purchase a

product compounded in a pharmacy, it is recommended to verify that the chosen

pharmacy follows the rules of good practices for handling magistral and

officinal preparations for human use in pharmacies.

4th step: Storage of possible evidence of

“unintentional” doping by the athlete (WADA, 2021)

As previously mentioned, the

unintentional doping of the athlete does not exempt them from possible punitive

consequences because even if unconsciously, this subject obtained advantages

over their opponents. However, it has been observed that in cases that athletes

claim and prove the absence of intent, sanctions can be mitigated. It is also

essential that possible contamination of food supplements can be identified, so

that measures can be taken in relation to their manufacturers. Therefore, it is

suggested that the following items be stored.

Duplicate of the same batch number of the food

supplement

Given step 1, that is, defining the

food supplement(s) essential for the health and/or performance of the elite

athlete, and step 2.3, the investigation of the history of the product

manufacturer desired (since it is impossible to analyze each product in the

laboratory), the next preventive measure consists of purchasing the product

together with a duplicate of the same lot number (step 3).

Since the early 2000s, it has been

accepted by the Court of Arbitration for Sport in Lausanne (Switzerland) that,

in some specific circumstances, unusual explanations can be provided to the

Panel to explain an adverse analytical finding (positive doping). This change

was considered the “opening of doors” for forensic investigations, as is done

in criminal courts. Therefore, a forensic approach may include testing

prohibited substances in food and beverages, but especially in dietary

supplements [57].

According to WADA [2021], the

athlete must keep a sample of the food supplement stored in a safe place,

preferably a duplicate with the same batch number and sealed. Thus, if the

athlete presents adverse analytical findings (positive doping), such duplicate

may be submitted for analysis to detect possible contamination with the

substance detected in the sample collected from the athlete. Therefore, this

duplicate should not be consumed (Figure 3).

In practice, the sealed duplicate

storage orientation may represent a substantial increase in the athletes'

monthly budget, as it means doubling the budget allocated to food

supplementation. However, when the use of a food supplement is common

throughout the season, such as a certain type of carbohydrate for intra-workout

consumption, it is possible to predict the amount to be consumed for a longer

period (for example, six months) and organize the acquisition of a greater

number of packs, all from the same lot, keeping only one duplicate for the six

months, which would have less impact on the athlete's budget. In this example,

it is essential to observe the product's shelf life.

Figure 3 - Food supplement storage

suggestion: for each product to be consumed, a duplicate with the same batch

number must be stored

Invoice in the name of the athlete, with product

description and batch number

In addition, to store a duplicate

of the food supplement consumed by an athlete, it is essential to prove that

the product was purchased by them. Therefore, the ABCD [21] guides the athlete

to store a copy of the invoice, which describes the name and ID number of the

athlete and the batch number of the purchased products. If the invoice is

generated automatically by some computerized system of the commercial

establishment and does not describe the lot number of the products, it is worth

requesting a separate statement listing the name and ID number of the athlete

and the lot numbers of the products purchased by them.

In practice, the athlete may

receive food supplementation from a sponsor, and the invoice would not be a

document involved in the process. In this case, it would be interesting for the

athlete to ask the sponsor for a duplicate of the food supplement with the same

batch number, accompanied by a signed and dated declaration, certifying that

the product, with that batch number, is being donated to the athlete, with the

name and ID number identified.

Nutritionist's prescription, with their license

number, professional stamp and signature

Under the World Anti-Doping Code,

which outlines the principle of strict liability, athletes are liable even when

a doping compound enters their bodies without their knowledge. It is the

personal duty of athletes to ensure that non-permitted substances do not enter

their bodies, and therefore, when instructed to consume a dietary supplement,

they must be aware that they are assuming the risk of unintentional doping.

However, if an

athlete is caught with positive doping and claims that the fact is due to

supposedly contaminated food supplements, ABCD [21] considers that proof of

prescription by a professional can strengthen the athlete's defense in court

responsible for this type of process.

5th step: Acquisition in physical stores

According to ABCD [21] guidelines,

online sales facilitate the sale and distribution of not safe and/or legal

products since, in most cases, sellers can close the company or change the name

or the page of the internet from another country. Additionally, the anonymity

and ease of opening and closing an online business has made the illegal

distribution of steroids, which can contaminate dietary supplements, a serious

problem.

On the other hand, in our searches,

no studies were found that compared different ways of acquiring food

supplements contaminated with substances prohibited by WADA, which suggests

that the hypothesis that “products sold online pose a greater risk of

contamination than those sold physically” has yet to be scientifically tested.

However, in

practice, the dietary supplements acquisition in duplicate, with the same lot

number (according to step 4 of the proposed protocol), is more feasible in

physical stores, as it is not always possible to choose the lot numbers when

making an online purchase.

6th step: Adequate completion of the

specific form when collecting a urine or blood sample for anti-doping analysis

When an athlete undergoes

anti-doping tests, in addition to collecting a urine or blood sample for later

laboratory analysis, it is also necessary to fill out a form through which some

facts are questioned, including the food supplements usage. In this way, it is

fundamental that the athlete registers all the food supplements that they are

consuming or that they recently have; because if they forget to mention the use

of these compounds and are caught with a positive test for prohibited

substances, it would be incoherent to claim that the cause of the contamination

is the food supplement.

Figure 4 - Unintentional doping risk

reduction protocol

Conclusion

The use of contaminated food

supplements is an important predictor of doping, and regulatory factors play a

fundamental role in the high availability of poor-quality products on the

market. The prevalence of contamination of supplements varies between 28 and

38%, with emphasis on sibutramine, testosterone, and other anabolic steroids,

fluoxetine, 1,3-dimethylamylamine, and hygenamine,

which, in addition to causing doping, are also capable of causing harm to the

health of the consumer. The degree of awareness of athletes about the subject

is low, and for this reason, we proposed a risk reduction protocol consisting

of six steps:

(1) Seek only strictly necessary

food supplements that present scientific evidence of efficacy and safety,

guided by a nutritionist;

(2) Analyze the quality of the

product available on the market: read the list of ingredients and arrange for

the product to be analyzed in the laboratory, either on your initiative or by

companies that test in batches and issue a quality seal, or through programs

government, if your country has such a strategy; if laboratory analysis is not

feasible, investigate the manufacturer's history, choose companies without

cases of adulteration, and move on to the next steps;

(3) Preferably purchase products

made by industry, or if you choose a compounding pharmacy, check that good

practices are being adopted for handling magistral and officinal preparations

for human use in pharmacies;

(4) Store possible evidence of

“unintentional” doping: duplicate product with the same batch number; invoice

with the athlete's name and product description with the batch number; the

nutritionist prescription, with their license number, professional stamp, and

signature;

(5) Acquire supplements preferably

in physical stores, avoiding the internet, so that you can choose the same

batch numbers;

(6) At the time of collecting

samples for anti-doping testing, fill in the form correctly and do not forget

to record all food supplements consumed recently.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financing source

There were no external sources of

funding for this study.

Authors' contribution

Research conception and

design: Mendes RR; Data collection: Mendes RR, Prado

JRS; Data

analysis and interpretation: Mendes RR, Prado JRS;

Statistical analysis: Mendes RR; Manuscript writing: Mendes RR, Prado

JRS; Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content:

Mendes RR

References

- Maughan RJ, Shirreffs SM, Vernec A. Making decisions about supplement use. Int J

Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2018;28(2):212-9. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0009 [Crossref]

- Guest NS, Van Dusseldorp TA,

Nelson MT, Grgic J, Schoenfeld BJ, Jenkins NDM, et

al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: caffeine and

exercise performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr.

2021;18(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12970-020-00383-4 [Crossref]

- Kerksick CM, Wilborn CD, Roberts MD, Smith-Ryan A, Kleiner SM, Jäger R, et al. ISSN exercise & sports nutrition review update: research & recommendations. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2018;15(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12970-018-0242-y [Crossref]

- Stellingwerff T, Heikura IA, Meeusen R, Bermon S, Seiler S, Mountjoy ML, et al. Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): shared pathways, symptoms and complexities. Sports Med. 2021;51(11):2251-80. doi: 10.1007/s40279-021-01491-0 [Crossref]

- Maughan RJ, Burke LM, Dvorak J, Larson-Meyer DE,

Peeling P, Phillips SM, et al. IOC consensus statement: dietary supplements and

the high-performance athlete. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(7):439-55. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099027 [Crossref]

- Daher J, Mallick M, El Khoury D. Prevalence of dietary supplement use among athletes worldwide: a scoping review. Nutrients. 2022;14(19). doi: 10.3390/nu14194109 [Crossref]

- Lauritzen F, Gjelstad A. Trends in dietary supplement use among athletes selected for doping controls. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1143187. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1143187 [Crossref]

- Thomas M, Kalicinski M. The effects of slackline balance training on postural control in older adults. J Aging Phys Act.2016;393-8. doi: 10.1123/japa.2015-0099 [Crossref]

- Hurst P. Are dietary supplements a gateway to doping? A retrospective survey of athletes’ substance use. Subst Use Misuse. 2023;58(3):365-70. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2022.2161320 [Crossref]

- Outram S, Stewart B. Doping through supplement use: a review of the available empirical data. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2015;25(1):54-9. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2013-0174 [Crossref]

- Kozhuharov VR, Ivanov K, Ivanova S. Dietary supplements as source of unintentional doping. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:8387271. doi: 10.1155/2022/8387271 [Crossref]

- WADA - World Anti-Doping Agency. Anti-doping code.

[Internet] 2021 [cited 2023 Jul 24]. Available from:

https://www.wada-ama.org/en/resources/world-anti-doping-program/world-anti-doping-code.

- Wierzejska RE. Dietary supplements-for whom? The current state of knowledge about the health effects of selected supplement use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17). doi: 10.3390/ijerph18178897 [Crossref]

- Richardson E, Akkas F,

Cadwallader AB. What should dietary supplement oversight look like in the US?

AMA J Ethics. 2022;24(5):E402-9. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2022.402 [Crossref]

- Cadwallader AB. Which features of dietary supplement industry, product trends, and regulation deserve physicians’ attention? AMA J Ethics. 2022;24(5):E410-18. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2022.410 [Crossref]

- Brasil.

Ministério da Saúde. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA).

Resolução da Diretoria Colegiada – RDC n°243, de 26 de julho de 2018. Dispõe

sobre os requisitos sanitários dos suplementos alimentares. Diário Oficial da

União. Brasília: Diário Oficial da União; 2018.

- Molin TRD, Leal GC, Muratt

DT, Marcon GZ, Carvalho LM, Viana C. Regulatory framework for dietary

supplements and the public health challenge. Rev Saúde Pública. 2019;53:90. doi: 10.11606/s1518-8787.2019053001263 [Crossref]

- Brasil.

Instrução Normativa - IN No 76, de 5 de novembro de 2020. Dispõe sobre a

atualização das listas de constituintes, de limites de uso, de alegações e de

rotulagem complementar dos suplementos alimentares. Brasília: Diário Oficial da

União; 2020.

- WADA - World Anti-Doping Agency. The prohibited list. [Internet]. 2023. [cited 2023 Jul 24]. Available from: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/prohibited-list

- Walpurgis K, Thomas A, Geyer H, Mareck U, Thevis M. Dietary supplement and food contaminations and their implications for doping controls. Foods. 2020;9(8). doi: 10.3390/foods9081012 [Crossref]

- ABCD -

Autoridade Brasileira de Controle de Dopagem. Apostila Antidopagem. {Internet].

2022. [cited 2023 Jul 24]. Available

from: https://www.gov.br/abcd/pt-br/composicao/educacao-e-prevencao/material-educativo-antidopagem-1.

2022

- Anderson JM. Evaluating the athlete’s claim of an

unintentional positive urine drug test. Curr Sports Med

Rep.2011;10(4):191-6. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e318224575f [Crossref]

- Silva LFM, Ferreira KS. Segurança alimentar de suplementos comercializados no Brasil. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2014;20(5). doi: 10.1590/1517-86922014200501810 [Crossref]

- Henao MMM. Desenvolvimento e aplicação de

método analítico para detecção de estimulantes em suplementos nutricionais

adulterados. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2018.

- Florentin M, Liberopoulos EN, Elisaf MS. Sibutramine-associated adverse effects: a practical guide for its safe use. Obes Rev. 2008;9(4):378-87. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00425.x [Crossref]

- James WPT, Caterson ID, Coutinho W, Finer N, Van Gaal LF, Maggioni AP, et al. Effect of sibutramine on cardiovascular outcomes in overweight and obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(10):905-17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003114 [Crossref]

- Scheen AJ. Cardiovascular risk-benefit profile of sibutramine. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2010;10(5):321-34. doi: 10.2165/11584800-000000000-00000 [Crossref]

- Torrisi M, Pennisi G, Russo I, Amico F, Esposito M, Liberto A, et al. Sudden cardiac death in anabolic-androgenic steroid users: a literature review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56(11). doi: 10.3390/medicina56110587 [Crossref]

- Karila T, Hovatta O, Seppälä T. Concomitant abuse of anabolic androgenic steroids and human chorionic gonadotrophin impairs spermatogenesis in power athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2004;25(4):257-63. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-819936 [Crossref]

- Ivanova S, Ivanov K, Pankova

S, Peikova L. Consequences of anabolic steroids

abuse. Farmatsiia [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2022 Set

12];61(4):44-50. Available from:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287323821_Consequences_of_anabolic_steroids_abuse

- Duiven E, van Loon LJC, Spruijt L, Koert W, de Hon OM. Undeclared doping substances are highly prevalent in commercial sports nutrition supplements. J Sports Sci Med. 2021;20(2):328-38. doi: 10.52082/jssm.2021.328 [Crossref]

- Leaney AE,

Heath J, Midforth E, Beck P, Brown P, Mawson DH.

Presence of higenamine in beetroot containing

“foodstuffs” and the implication for WADA-relevant anti-doping testing. Drug Test

Anal. 2023;15(2):173-80. doi: 10.1002/dta.3383 [Crossref]

- Zhang Y, Wu X, Wang W, Huo J, Luo J, Xu Y, et al. Simultaneous detection of 93 anabolic androgenic steroids in dietary supplements using gas chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2022;211:114619. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2022.114619 [Crossref]

- Rodriguez-Lopez P, Rueda-Robles A, Sánchez-Rodríguez L, Blanca-Herrera RM, Quirantes-Piné RM, Borrás-Linares I, et al. Analysis and screening of commercialized protein supplements for sports practice. Foods. 2022;11(21). doi: 10.3390/foods11213500 [Crossref]

- Mallick M, Camacho CB, Daher J, El Khoury D. Dietary supplements: a gateway to doping? Nutrients. 2023;15(4):881. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2022.2161320 [Crossref]

- Froiland K, Koszewski W, Hingst J, Kopecky L. Nutritional supplement use among college athletes and their sources of information. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2004;14(1):104-20. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.14.1.104 [Crossref]

- Tian HH, Ong WS, Tan CL. Nutritional supplement use

among university athletes in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2009;50(2):165-72.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19296032/

- Dodge T. Consumers’ perceptions of the dietary supplement health and education act: implications and recommendations. Drug Test Anal. 2016;8(3-4):407-9. doi: 10.1002/dta.1857 [Crossref]

- Braun H, Koehler K, Geyer H, Kleiner J, Mester J, Schanzer W. Dietary supplement use among elite young German athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2009;19(1):97-109. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.19.1.97 [Crossref]

- Torres-McGehee TM, Pritchett KL, Zippel D, Minton DM, Cellamare A, Sibilia M. Sports nutrition knowledge among collegiate athletes, coaches, athletic trainers, and strength and conditioning specialists. J Athl Train. 2012;47(2):205-11. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.2.205 [Crossref]

- Baylis A, Cameron-Smith D, Burke LM. Inadvertent doping through supplement use by athletes: assessment and management of the risk in Australia. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2001;11(3):365-83. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.11.3.365 [Crossref]

- Chan DKC, Donovan RJ, Lentillon-Kaestner V, Hardcastle SJ, Dimmock JA, Keatley DA, et al. Young athletes’ awareness and monitoring of anti-doping in daily life: Does motivation matter? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25(6):e655-63. doi: 10.1111/sms.12362 [Crossref]

- Hon O, Coumans B. The continuing story of nutritional supplements and doping infractions. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(11):800-5; discussion 805. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.037226 [Crossref]

- Wardenaar FC, Hoogervorst D, Vento KA, de Hon PhD O. Dutch olympic and non-olympic athletes differ in knowledge of and attitudes toward third-party supplement testing. J Diet Suppl. 2021;18(6):646-54. doi: 10.1080/19390211.2020.1829248 [Crossref]

- Erdman J, Oria M, Pillsbury L. Nutrition and traumatic brain injury: improving acute and subacute health outcomes in military personnel. In: Erdman J, Oria M, Pillsbury L, eds. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. doi: doi: 10.17226/13121 [Crossref]

- Lewis M, Ghassemi P, Hibbeln J. Therapeutic use of omega-3 fatty acids in severe head trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(1):273e5-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.05.014 [Crossref]

- Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. American College of

Sports Medicine joint position statement. Nutrition and athletic performance.

Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(3):543-68. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000852 [Crossref]

- Pereira

C, Veiga N. Educação para a saúde baseada em evidências. Millenium. Journal of Education Technologies and Health

[Internet]. 2014 [cited 2022 Jun 12];46(46):107-36. Available from:

https://revistas.rcaap.pt/millenium/article/view/8144

- Porrini M, Del Bo? C. Ergogenic aids and supplements. Front Horm Res. 2016;47:128-52. doi: 10.1159/000445176 [Crossref]

- Judkins CMG, Teale P, Hall DJ. The role of banned substance residue analysis in the control of dietary supplement contamination. Drug Test Anal. 2010;2(9):417-20. doi: 10.1002/dta.149 [Crossref]

- Kamber M, Baume N, Saugy M, Rivier L. Nutritional supplements as a source for positive doping cases? Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2001;11(2):258-63. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.11.2.258 [Crossref]

- Khazan M, Hedayati M, Kobarfard F, Askari S, Azizi F. Identification and

determination of synthetic pharmaceuticals as adulterants in eight common

herbal weight loss supplements. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(3):e15344. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.15344 [Crossref]

- Mathews NM. Prohibited contaminants in dietary

supplements. Sports Health.

2018;10(1):19-30. doi: 10.1177/1941738117727736 [Crossref]

- Gueorguieva EP, Ivanov K, Gueorguiev S, Mihaylova A, Madzharov V, Ivanova S. Detection of sibutramine in herbal food supplements by UHPLC/HRMS and UHPLC/MS-MS. Biomedical Research. 2018;29(14). doi: 10.4066/biomedicalresearch.29-18-879 [Crossref]

- Cohen PA, Travis JC, Keizers PHJ, Boyer FE, Venhuis BJ. The stimulant higenamine in weight loss and sports supplements. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57(2):125-30. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2018.1497171 [Crossref]

- Leaney AE, Beck P, Biddle S, Brown P, Grace PB, Hudson SC, et al. Analysis of supplements available to UK consumers purporting to contain selective androgen receptor modulators. Drug Test Anal. 2021;13(1):122-7. doi: 10.1002/dta.2908 [Crossref]

- Kintz P. The forensic response after an adverse analytical finding (doping) involving a selective androgen receptor modulator (SARM) in human athlete. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2022;207:114433. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2021.114433 [Crossref]