Rev Bras

Fisiol Exerc. 2023;22:e225470

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Reproducibility of inhibitory control, working memory,

and cognitive flexibility measures in older women

Reprodutibilidade

de medidas do controle inibitório, memória de trabalho e flexibilidade

cognitiva em mulheres idosas

Alan

Pantoja-Cardoso1, José Carlos Aragão-Santos1, Marcos

Raphael Pereira Monteiro1, Poliana de Jesus Santos1, Ana

Carolina Dos-Santos1, Heloiana Faro2, Juan Ramon Heredia-Elvar3,

Leonardo de Sousa Fortes2, Marzo Edir Da Silva-Grigoletto1

1Universidade

Federal de Sergipe, São Cristóvão, SE, Brasil

2Universidade

Federal de Paraíba, Brasil

3Universidad

Alfonso X El Sabio, Madrid, Espanha

Received: February 2, 2023; Accepted: March 5, 2023.

Correspondence: Alan Pantoja Cardoso, alan_pantoja1996@hotmail.com

Como citar

Pantoja-Cardoso A, Aragão-Santos JC, Monteiro MRP, Santos PJ,

Dos-Santos AC, Faro H, Heredia-Elvar JR, Fortes LS,

Silva-Grigoletto ME. Reproducibility of inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive

flexibility measures in older women. Rev Bras

Fisiol Exerc 2023;22:e225470. doi: 10.33233/rbfex.v22i1.5470

Abstract

Introduction: Executive Function is expressed in day-to-day

activities through inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive

flexibility. Despite the importance of evaluating these measures, there are

disagreements about the reproducibility of the tests. Objective: To test

the reproducibility of the Stroop Color-Word Test, Corsi

Block-Tapping Test, and Trail Making Test in older women. Methods:

Thirty-five older women performed the Stroop Color-Word Test (Inhibitory

Control), Corsi Block-Tapping Test (Working Memory),

and Trail Making Test (Cognitive Flexibility) within one week between the test

and retest. The reproducibility of the tests was determined by the intraclass

correlation coefficient, coefficient of variation, standard error of

measurement, and visual inspection of the Bland-Altman graphs. Results:

The Stroop Color-Word Test showed satisfactory reproducibility values only for

congruent and incongruent measures, with excellent intraclass correlation

coefficient values. Corsi Block-Tapping Test showed

reproducible values with a moderate and good intraclass correlation coefficient

for the sequence and composite score, respectively. The Trail Making Test

showed reproducible values for parts A, B, and the ratio (B/A), with intraclass

correlation coefficients between moderate and good. Visual inspection of the

Bland-Altman plots showed low bias in all variables. Conclusion: The

results of the Stroop Color-Word Test, for congruent and incongruent trials,

the sequence and the composite score of the Corsi

Block-Tapping Test, as well as the part A, B, and the ratio (B/A) of the Trail

Making Test, are reproducible measurements for older women.

Keywords:

test-retest reliability; executive function; old people; neuropsychological

tests.

Resumo

Introdução: A

Função Executiva é expressa nas atividades do dia a dia por meio do controle

inibitório, memória de trabalho e da flexibilidade cognitiva. Apesar da

importância de avaliar essas medidas, existem divergências sobre a

reprodutibilidade dos testes. Objetivo: Testar a reprodutibilidade do Stroop Color-Word Test, Teste dos Cubos de Corsi e Teste de

Trilhas em mulheres idosas. Métodos: Trinta e cinco mulheres idosas

realizaram o Stroop Color-Word Test (Controle

Inibitório), Teste dos Cubos de Corsi (Memória de Trabalho) e Teste de Trilhas

(Flexibilidade Cognitiva) com uma semana entre o teste e reteste. A reprodutibilidade

dos testes foi determinada pelo coeficiente de correlação intraclasse,

coeficiente de variação, erro padrão da medida e inspeção visual dos gráficos

de Bland-Altman. Resultados: O Stroop Color-Word Test apresentou valores satisfatórios quanto

à reprodutibilidade apenas para as medidas congruentes e incongruentes, com

valores excelentes de coeficiente de correlação intraclasse. O Teste dos Cubos

de Corsi apresentou valores reprodutíveis com coeficiente de correlação

intraclasse moderado e bom para a sequência e escore composto, respectivamente.

O Teste de Trilhas apresentou valores reprodutíveis para as partes A, B e a

razão (B/A), com coeficientes de correlação intraclasse entre moderado e bom. A

inspeção visual nos gráficos de Bland-Altman

demonstrou baixo viés em todas as variáveis. Conclusão: Os resultados do

Stroop Color-Word Test, para ensaios congruentes e

incongruentes, a sequência e o escore composto do Teste dos Cubos de Corsi,

assim como a parte A, B e a razão (B/A) do Teste de Trilha são medidas

reprodutíveis para mulheres idosas.

Palavras-chave:

confiabilidade do teste-reteste; função executiva; pessoas idosas; testes

neuropsicológicos.

Introduction

Executive Function (EF) is about

higher mental processes that ensure a person engages in day-to-day behaviors

[1]. EF includes necessary skills when attentional resources are required

throughout a task, in addition to being used for automatic and intuitive

cognitive processes [1]. It allows the individual to reflect before acting,

work on different ideas, solve unexpected challenges, think from different

perspectives, reconsider divergent opinions, and avoid distractions [2]. The

proper functioning of the EF is essential for maintaining the quality of life

[3,4]. Among the EF domains, the most studied are inhibitory control, working

memory, and cognitive flexibility.

Inhibitory control is responsible

for inhibiting mental and behavioral processes to the detriment of an

objective, such as adapting actions to external objections; for example, in a

conversation, we do not say everything we think and feel. It is necessary to

choose what to say according to the social context [5]. Working memory, in

turn, is seen as the manipulation of memory according to the required demand;

for example, when cooking according to a recipe, it is necessary to follow

steps properly to achieve the desired result [6]. Finally, cognitive

flexibility is the mental process related to adapting to challenges or events,

being used to make adjustments to previously planned actions or to create

something in a context; for example, when we have several options and need to

choose only a few of them to achieve a result [1].

The literature presents several

tasks to assess inhibitory control. The most popular ones are the Go/No-Go

paradigms [7], the Flanker task [8], and the Stroop Color-Word Test (SCWT) [9].

The Go/No-Go is a task with different stimuli, some that must be answered and

some that must not. For example, the subject must react when viewing an arrow

to the right, while he must not react to seeing an arrow to the left [10]. The

Flanker task, in turn, is based on the use of sets of arrows or symbols that

can be congruent (e.g., all arrows in the same direction

“<<<<<”), incongruent (e.g., different directions “>>

<>>”), or neutral (e.g., including arrows and other symbols

“---<--”) [8]. Finally, the most common is the SCWT, which is based on names

of colors that are filled in by the same color as the word indicates (congruent)

or a different color (incongruent), and the subject must indicate the filling

color, not inhibiting the reading of the which is written [9]. The SCWT has a

vast literature, but there are divergences regarding the scoring and

reproducibility of this test [11,12,13,14]. In this sense, it is necessary to

evaluate the reproducibility of the SCWT in a computerized way in elderly

individuals, standardizing its form of execution and scoring.

Working memory, in turn, can be

assessed through verbal or non-verbal tasks. The N-back test explores verbal

and non-verbal tasks, while the Corsi Block-Tapping

Test (CBTT) is non-verbal [15,16,17]. In the N-back test, the individual must

remember previous numbers or images, which can be called 1-back (remembering

the displayed number before the current number), 2-back (remembering the

displayed number before the last two numbers presented), and so on, making it

possible to assess both response time and accuracy [15]. The CBTT assesses

visuospatial working memory, asking the participant to select squares in the

same order in which they were presented (direct order) or in reverse order,

starting from the last square presented to the first. In the CBTT, it is

possible to evaluate the composite score (sequence x number of correct answers)

or only the sequence of correct answers. However, the literature still differs

on the best score to be adopted, besides not presenting good reproducibility

values even when performing six tests with one-week intervals, mainly with

older people [18,19,20].

Cognitive flexibility is understood

as a result of inhibitory control and working memory since it is necessary to

inhibit a premeditated action (inhibitory control) and check alternatives to

act differently compared to previous experiences (working memory) [1]. The Trail

Making Test (TMT) and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task are two approaches to

assessing cognitive flexibility [1,21,22]. In the Wisconsin card sorting task,

the participant must match cards from a deck totaling 128 with four target

cards dealt on the table. Cards can be combined based on their colors “red,

blue, yellow or green” or geometric shapes “crosses, circles, triangles or

stars”. The test combines ten cards based on colors or geometric shapes [23].

The TMT, in turn, consists of a task divided into two parts, A and B. The TMT-A

assesses the processing speed by considering the time the participant uses to

connect 25 dots in ascending numerical order. The TMT-B represents the visual

search and the cognitive flexibility when evaluating the connection of numbers,

and letters in ascending and intercalated order (e.g., a number and a letter)

arranged randomly. Thus, the TMT-B includes inhibitory control when verifying

the non-linking of a letter with a letter or number with a number and working

memory when needing to remember the increasing numerical and alphabetic

sequence after each connection. Among the ways of analyzing the TMT score is

the difference (B-A) and the ratio (B/A) in the execution time [19,24,25]. In

this sense, the study by Wang et al. [25] showed moderate

reproducibility for TMT-A and excellent reproducibility for TMT-B in elderly

individuals. However, they do not address other measures such as the difference

(B-A) and the ratio (B/A), in addition to the fact that the literature does not

present a consensus on its use for the public of older women and the interval

between test and retest applications.

In this sense, it is necessary to

analyze what is more relevant considering the evaluation of EF: evaluating only

one domain in isolation or applying different tests to different domains.

Consequently, the application of various EF tests in sequence, as well as the

reapplication interval and target audience, may affect the reproducibility of

EF tests. Therefore, we aimed to test the reproducibility of SCWT, CBTT, and

TMT in older women sequentially using a seven-day interval between

measurements. We believe that, when considering the sample involved in the

study, seven days is the most appropriate to minimize the learning effect and

ensure better reproducibility in the tests. Additionally, we believe that even

when applied sequentially, the tests will present good reproducibility compared

to the values shown in the literature, allowing a consistent evaluation of the

main EF domains.

Methods

Participants

A total of 70 women were recruited

through leafleting around the Prof. José Aloísio de

Campos campus from the Federal University of Sergipe in São Cristovão.

Inclusion criteria were: having at least 12 Montreal Cognitive Assessment

(MoCA) points; being physically independent; being aged between 60 and 79

years; being literate. In turn, the exclusion criteria were: having color

blindness; neurological and/or psychiatric disorders (e.g., Parkinson's

disease); hearing or visual impairment incompatible with the neuropsychology of

the tests; and not having a fine motor impairment that could interfere with the

performance of cognitive and motor tasks.

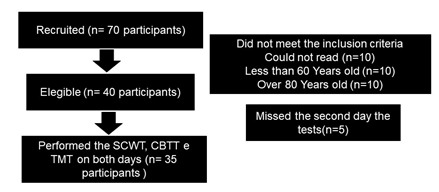

After

the screening, 40

participants met the inclusion criteria, and 35 participants performed

the

three tests proposed in the study sequentially and with an interval of

seven

days between the test and the retest (Figure 1). Before data

collection, the

participants signed the informed consent form (TCLE) after explaining

all the

procedures. The research was submitted to the institution’s

ethics committee, approved under opinion 3.225.938, and followed the

Declaration of Helsinki for research with human beings.

Figure

1 - Participants' flowchart

Executive Function Protocol

Initially, body mass and height

measurements were obtained to calculate the body mass index (BMI). The MoCA

questionnaire was applied, which involves EF, visuospatial

working memory, episodic memory, and attention to assess the global cognition

of older people [26,27].

Each participant visited the

laboratory in three different sessions: the first for sample characterization

and two with an interval of seven days between them to perform the tests in the

morning. Each session lasted 30 minutes. Aiming to keep the participants, a

reminder was given three days before the sessions to confirm participation.

Before the measurements, the participants were familiarized with the devices

used to carry out the tests.

On the day before the tests, the

participants were instructed through a call and message to abstain from alcohol

and vigorous physical activity for 24 hours, in addition to not smoking or

ingesting caffeine within two hours before the experiment. The tests were

conducted between March and November 2022 and were always applied by the same

evaluator.

The SCWT and CBTT tests were

performed on computers with a 15-inch screen. The PsychoPy®

program version 2022 1.3 (https://www.psychopy.org/) was used to build the

stimuli and set up the experiment, and it was made available online through the

Pavlovia platform (https://pavlovia.org/). The

participants used keyboards with yellow, blue, green, and red stickers on the A,

D, J, and L keys to perform commands during the tests.

The participant rested for five

minutes before the tests, and then the tests started. For this, the participant

remained seated, facing a monitor at a distance of 50 cm. Then, the tests were applied

in the following order: SCWT, CBTT, and TMT. Instructions for each task were

provided verbally and in writing on the computer screen.

Stroop Color-Word Test (SCWT)

SCWT assesses inhibitory control

[11]. The test has congruent (word meaning equal to its font color) and

incongruent (word meaning and font color divergent) responses. First, the

participant performed 10% of the trials for familiarization with the

experiment, resulting in 12 trials out of 120. Then, the participants completed

120 trials, 60 congruent and 60 incongruent. During the test, participants were

asked to respond as quickly as possible. The response time (RT) for congruent

stimuli and the RT for incongruent stimuli that expresses inhibitory control

were analyzed. Furthermore, we analyzed the mean difference in performance

between congruent and incongruent trials, commonly called the Stroop effect,

which is yet another measure of inhibitory control [14]. The test was

considered valid when the participant obtained an accuracy of at least 80%.

Corsi Block-Tapping Test (CBTT)

This test evaluates visuospatial

working memory [19]. At the beginning of the test, there were four

familiarization trials with only two squares, in which they got hit-or-miss

feedback. Our test consisted of nine squares (2 cm x 2 cm) in blue, and every

500 ms, a square changed color, turned yellow, and

then returned to blue at random. Then, the participant was asked to indicate

which changed color in the same order in which the changes occurred (direct

order). The participants received no feedback regarding the successes and

errors in the test. If the participant got the sequence right, the test

progressed by increasing the number of squares. On the other hand, if the

participant made a mistake twice in a row, the test was terminated. In this

test, the applicator helped the participants by using the mouse to select the

sequence they indicated since they were unfamiliar with the mouse. The values

referring to the sequence the participant reached in a given trial and the

composite score calculated by multiplying the number of correct answers

obtained in all trials by the sequence score were used for analysis.

Trail Making Test (TMT)

This test assesses cognitive

flexibility [22]. The TMT consisted of two parts: in part A, participants were

asked to continuously call, using a ballpoint pen, numbers from 1 to 25

randomly arranged on a sheet of paper. In part B, participants were asked to

continuously connect numbers and letters alternately (e.g., 1-A, 2-B, etc.).

The score on both parts is defined by the time to run the test correctly. Then,

the difference (B-A) is taken as an index of cognitive flexibility, and the

higher the score, the lower the participant's cognitive flexibility [28]. In

addition, the ratio (B/A) was calculated, which is also an estimate of

cognitive flexibility. In the test application, we followed Reitan's

recommendation [22], in which errors were not accounted for. In case of error,

the evaluator indicated that the participant returned to the last number or

letter and continued the test [28].

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated

using the G*Power 3.1.9.7 software based on an unpublished pilot study,

considering an alpha error of 0.05, power of 0.95, and the ratio between the

alternative and null hypothesis equivalent to 0,35 resulting in a minimum

sample of 27 participants [29,30]. This sample calculation method was

previously used by Fontes et al. [31]. All data were analyzed using the

JAMOVI software, version 2.3.16. Data normality was tested using the

Shapiro-Wilk test. The reproducibility of SCWT, CBTT, and TMT was determined by

the two-way intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). The ICC was interpreted

according to the Koo et al. [32] classification system for

reproducibility: < 0.50 = poor; 0.50-0.75 = moderate; 0.75-0.90 = good; and

> 0.90 = excellent. In addition, the coefficient of variation (CV) and

standard error of measurement (SEM) were calculated. The level of agreement between

sessions was analyzed using the Bland-Altman plot, considering the systematic

bias and its limits of agreement of 95% (LoA = Bias) [33]. Additionally, data on the sum of the differences between the

means on the two evaluation days were analyzed to visualize the agreement

between the measurements better. Graphs were constructed using GraphPad Prism

software version 8.

Results

Namely, the sample analyzed had an

average age of 66.4 ± 5.4 years, a body mass of 67.1 ± 11.5 kg, a height of 1.55

± 0.05 m, and a BMI of 28.0 ± 4.2 kg/m2. In addition, the

participants had an average score of 21.9 ± 3.83 points on the MoCA.

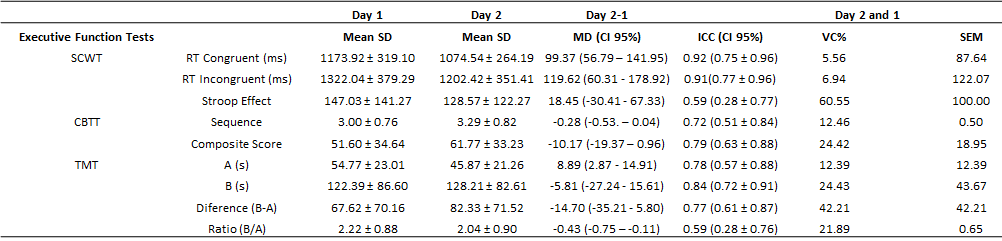

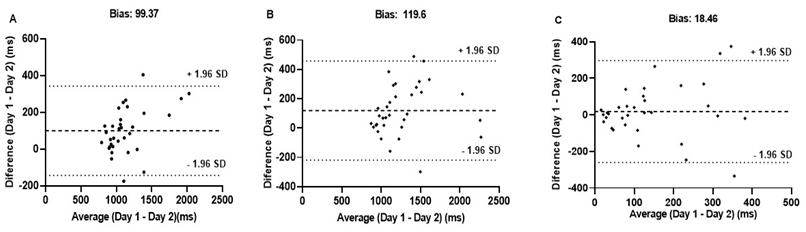

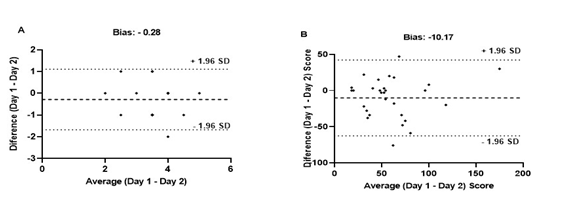

Regarding the Congruent and

Incongruent RT of the SCWT, an excellent ICC, low CV, and SEM within the

expected range were observed (Table I). We detected low bias for the two

measures based on the agreement analysis with only two individuals beyond the

agreement interval (Figure 2). Regarding SE, we observed a moderate ICC and SEM

within the expected range but a high CV (Table I). In addition, the agreement

between measurements showed a bias close to zero, and only three individuals

were outside the limits of agreement (Figure 2).

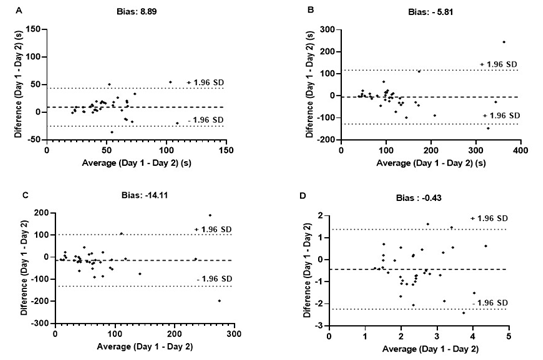

Regarding the CBTT, the sequence

analysis results showed moderate ICC, low CV, and SEM within the expected range

(Table I). There was a bias close to zero in the agreement between

measurements, and only one individual exceeded the limits of agreement (Figure

3). The composite score demonstrated a good ICC, low CV, and within the

expected SEM (Table I). Finally, the agreement between the measures had a bias

close to zero, and only one individual was outside the limits of agreement

(Figure 3).

Regarding TMT-A and TMT-B, a good

ICC, low CV, and SEM within the expected range were verified (Table I).

Regarding the agreement between measurements, we found a bias close to zero in

both variables, with two individuals exceeding the limit of agreement in the

TMT-B (Figure 4). Using other measures of cognitive flexibility, specifically,

the difference (B-A), good ICC, high CV, and within expected SEM were observed

(Table I). The agreement between measurements showed a bias close to zero with

two individuals outside the agreement limit. In the ratio (B/A), a moderate

ICC, low CV, and SEM within the expected range were detected (Table I). The

agreement between measurements showed a bias close to zero, and only one

individual was outside the limits of agreement (Figure 4).

SD

= Standard Deviation; MD = Mean Difference; CI = Confidence Interval; ICC =

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient; CV = Coefficient of Variation; SEM =

Standard Error of Measurement; RT = Response Time; SCWT = Stroop Color-Word

Test; TMT = Trail Making Test; CBTT = Corsi

Block-Tapping Test

Figure

2 - Bland-Altman plots of differences between Day 1

and Day 2 as a function of the mean of paired measurements for RT Congruent (A)

and RT Incongruent (B) and the Stroop effect (C). The dotted line represents

the systemic bias, and the dashed lines represent the upper and lower limits of

agreement

Figure

3 - Bland-Altman plots of differences between Day 1

and Day 2 as a function of the mean of paired measures for the CBTT sequence

(A) and the CBTT composite score (B). The dotted line represents the systemic

bias and the dashed lines represent the upper and lower limits of agreement

Figure

4 - Bland-Altman plots of differences between Day 1

and Day 2 as a function of the mean of paired measurements for TMT-A (A), TMT-

B (B), difference (B-A) (C), and ratio (B/A) (D). The dotted line represents

the systemic bias and the dashed lines represent the upper and lower limits of

agreement

Discussion

The present study’s findings

partially corroborate our hypothesis since some of the results obtained in each

test were reproducible in older adult women. RT congruent and incongruent

results for the SCWT, composite score values for the CBTT, and the TMT-A,

TMT-B, and ratio (B/A) measures. Furthermore, the time interval used and the

application of the tests in sequence do not affect the reproducibility of the

measurements. Thus, our findings help outline research investigating the EF of

older women [34].

In the concordance analyses, we

found excellent reproducibility in the SCWT congruent and incongruent RT, low

CV, and low bias. However, the Stroop effect showed moderate reproducibility

and high CV. These findings corroborate those presented by Wang et al.

[24], who evaluated the reproducibility in older people in the congruent and

incongruent RT and demonstrated a value classified as excellent (ICC = 0.91)

with a period between the test and retest of three to seven days.

Interestingly, Wang et al. [24] applied the SCWT using pencil and paper

while we performed it using computers. Thus, there may be no significant impact

on the measurement of inhibitory control with different application forms.

However, the application through computers makes it easier from the application

to the evaluation and number of tests applied [20,35]. These findings apply to

older women since other studies with young adults found values below those

presented in the present study [12].

Regarding the CBTT values, the

sequence and the composite score were analyzed, demonstrating that both

variables have good reproducibility. These values differ from the study by

White et al. [20] in which direct order CBTT was applied to 30 healthy

older men, showing poor reproducibility in sequence and composite score

measures [20]. A possible explanation may be given by the help of the

applicator in handling the mouse, which is an important aspect when considering

the application of this test in a computerized way to guarantee the quality of

the measurement since the older adult population tends to present deficits in

fine motor control and low familiarization with the use of the mouse [36].

Regarding cognitive flexibility,

the values referring to TMT-A, B, and difference (B-A) presented a good classification

in the ICC. In contrast, the ratio (B/A) showed a moderate ICC. It is also

important to note that the CV for TMT-A, TMT-B, and the ratio (B/A) were

classified as low. These findings partially corroborate with other studies that

analyzed the same population, such as the findings of Park and Shott [37], who

evaluated TMT-A and TMT-B measurements in older people, finding an excellent

ICC. However, in these studies, the authors considered individuals 50 years old

as older people. Another study applying the Chinese version of the TMT

addressed test reproducibility in older people and demonstrated a good ICC in

TMT-A and excellent in TMT-B using an evaluation interval similar to that of

the present study, from three to seven days [25]. A possible reason for the

differences is the diversity of education in the sample between the studies

since we do not require a minimum education level. Another important point of

our study is the standardization of the interval between applications. It is

also worth mentioning that we maintained the performance of this test with pen

and paper since the literature recommends the application in this way [38,39].

Although the tests used alone are

reported in the literature as general indicators of EF, each assesses a domain

in isolation. A strength of our study was an integrated approach, using SCWT to

assess inhibitory control, CBTT for working memory, and TMT to assess cognitive

flexibility, thus favoring the interpretation of the global state of EF [11].

In turn, we adopted the application of SCWT and CBTT in a computerized way

based on free access protocols and software, which facilitates the method of

reproduction used in clinical practice and scientific research. In addition to

innovating by bringing the reproducibility of neurocognitive tests in a

computerized format in older people, this is relatively scarce in the

literature [20]. Thus, our findings provide important insights for a

comprehensive assessment and follow-up of EF in older women.

Among the limitations of the

present study, we can point out the possibility of the learning effect since

only two measurements were performed for the test and retest. However, we

believe that the seven-day interval between measurements minimizes this effect.

Furthermore, to reduce the learning effect, the SCWT and CBTT tests were

planned with the sequences of words and blocks randomized between the test and

retest days.

Another limitation is the small

sample size, which may increase the chance of type I or II error, although we

met our sample calculation. In this sense, the literature has no consensus

about the best way to calculate sample size for reproducibility studies.

Furthermore, most studies used two groups, and we used only one. Thus, there

may be differences compared to other groups. Anyway, considering the normality

of the data, we believe that the results observed in the present study

contribute to the literature regarding tests for EF in older

women since we provide detailed information on the characteristics of the

tasks, instructions, stimuli, and scoring methods, presenting itself as an

important differential for other studies in the area [40]. In addition, we

provide score values that can be considered in other scientific studies and clinical

practice.

Conclusion

The evaluation of the congruent and

incongruent RT in the SCWT for inhibitory control, the sequence and a composite

score of the CBTT for visuospatial working memory, and the TMT-A, TMT-B and the

ratio (B/A) in the TMT for cognitive flexibility are reproducible methods for

assessing EF in older women. In addition, carrying out the tests sequentially

and with an interval of one week is an effective approach to guarantee the

reproducibility of these evaluations.

Academic

affiliation

This

article represents part of Alan Pantoja Cardoso's Master's thesis, supervised

by Professor Dr. Marzo Edir

Da Silva-Grigoletto, from

the Federal University of Sergipe, Brazil.

Conflict

of interest

There

is no conflict of interest

Funding

source

Part

of this study is funded by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher

Education Personnel - Brazil (CAPES)

Authors’ contributions

Research conception

and design: Pantoja-Cardoso A, Faro HKC; Data collection: Pantoja-Cardoso A, Dos-Santos AC, Santos

PJ; Data analysis and interpretation: Pantoja-Cardoso A, Aragão-Santos JS; Manuscript writing:

Pantoja-Cardoso A, Aragão-Santos JS, Monteiro MCP, Santos PJ, Heredia-Elvar JR, Dos-Santos AC; Critical

review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Fortes

LS, Da Silva-Grigoletto ME

- Diamond A. Executive Functions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64:135-68. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750 [Crossref]

- Diamond A. Why improving and assessing EF early in life is critical. In: Griffin JA, McCardle P, Freund LS, eds. Executive function in preschool-age children: Integrating measurement, neurodevelopment, and translational research. American Psychological Association 2016;11-43. doi: 10.1037/14797-002 [Crossref]

- Harada CN, Love MCN, Triebel KL. Normal cognitive aging. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(4):737-52. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2013.07.002 [Crossref]

- Ho H-T, Lin S-I, Guo N-W, Yang YC, Lin MH, Wang CS. Executive function predict the quality of life and negative emotion in older adults with diabetes: A longitudinal study. Prim Care Diabetes. 2022;16:537-42. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2022.05.002 [Crossref]

- Aron AR, Robbins TW, Poldrack

RA. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex: one decade on. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(4):177-85. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.12.003 [Crossref]

- Jonides J, Lewis RL, Nee DE, Lustig CA, Berman MG, Moore KS. The mind and brain of short-term memory. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:193-224. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093615 [Crossref]

- Donders FC. On the speed of mental processes. Acta Psychol (Amst). 1969;30:412-31. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(69)90065-1 [Crossref]

- Servant M, Logan GD. Dynamics of attentional focusing in the Eriksen flanker task. Atten Percept Psychophys. 2019;81(8):2710-2721. doi: 10.3758/s13414-019-01796-3 [Crossref]

- Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology 1935;18:643-62. doi: 10.1037/h0054651 [Crossref]

- Verbruggen F, Logan GD. Response inhibition in the stop-signal

paradigm. Trends Cogn Sci 2008;12:418-24. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.07.005 [Crossref]

- Scarpina F, Tagini S. The stroop color and word test. Front Psychol 2017;8:1-8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00557 [Crossref]

- Strauss GP, Allen DN, Jorgensen ML, Cramer SL. Test-retest reliability of standard and emotional stroop tasks: an investigation of color-word and picture-word versions. Assessment. 2005;12(3):330-7. doi: 10.1177/1073191105276375 [Crossref]

- Periáñez JA, Lubrini G,

García-Gutiérrez A, Ríos- Lago M. Construct validity of the stroop

color-word test: influence of speed of visual search, verbal fluency, working

memory, cognitive flexibility, and conflict monitoring. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2021;36(1):99-111. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acaa034 [Crossref]

- Ward N, Hussey E, Alzahabi

R, Gaspar JG, Kramer AF. Age-related effects on a novel dual-task Stroop

paradigm. PLoS ONE 2021;16:e0247923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247923 [Crossref]

- De Nardi T, Sanvicente-Vieira B,

Prando M, Stein LM, Fonseca RP, Grassi-Oliveira R. Tarefa N-back

Auditiva: Desempenho entre diferentes grupos etários. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2013;26(1). doi: 10.1590/S0102-79722013000100016 [Crossref]

- Gonçalves VT, Mansur LL. N-Back auditory test performance in normal individuals. Dement Neuropsychol. 2009;3(2). doi: 10.1590/S1980-57642009DN30200008 [Crossref]

- Nyberg L, Dahlin E, Stigsdotter Neely A, et al. Neural correlates of variable working memory load across adult age and skill: Dissociative patterns within the fronto-parietal network. Scand J Psychol. 2009;50(1):41-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2008.00678.x [Crossref]

- Arce T, McMullen K. The Corsi

Block-Tapping Test: Evaluating methodological practices with an eye towards

modern digital frameworks. Computers in Human Behavior Reports [Internet]. 2021

[cited 2022 dez 12];4:100099.

Available from: https://par.nsf.gov/servlets/purl/10292489

- Corsi PM. Human memory and the medial temporal region of

the brain [Internet]. Dissertation Abstracts International 1973;34(2-B): 891.

Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1976-04900-001

- White N, Flannery L, McClintock A, Machado L. Repeated computerized cognitive testing: Performance shifts and test–retest reliability in healthy older adults. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2019;41:179-91. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2018.1526888 [Crossref]

- Milner B. Some cognitive effects of frontal-lobe

lesions in man. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1982 Jun 25;298(1089):211-26. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1982.0083 [Crossref]

- Reitan RM. The relation of the Trail Making Test to organic

brain damage. J Consult Psychol.

1955;19(5):393-4. doi: 10.1037/ [Crossref]

- Miguel

FK. Teste Wisconsin de Classificação de Cartas. Avaliação Psicológica 2005;4:203-4.

- Suzuki H, Sakuma N, Kobayashi M, Ogawa S, Inagaki H, Edahiro A, e t al. Normative data of the Trail Making Test among urban community-dwelling older adults in Japan. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:832158. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.832158 [Crossref]

- Wang R-Y, Zhou J-H, Huang Y-C, Yang Y-R. Reliability of the Chinese version of the Trail Making Test and Stroop Color and Word Test among older adults. Int J Gerontol. 2018;12:336-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijge.2018.06.003 [Crossref]

- Cesar KG, Yassuda MS, Porto FHG, Brucki SMD, Nitrini R. MoCA Test: normative and diagnostic accuracy data for seniors with heterogeneous educational levels in Brazil. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2019;77(11). doi: 10.1590/0004-282X20190130 [Crossref]

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [Crossref]

- Bowie CR, Harvey PD. Administration and interpretation of the Trail Making Test. Nat Protoc 2006;1:2277-81. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.390 [Crossref]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, et al. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41:1149-60. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 [Crossref]

- Shieh G. Sample size requirements for the design of reliability studies: precision consideration. Behav Res Methods. 2014;46(3):808-22. doi: 10.3758/s13428-013-0415-1 [Crossref]

- Fontes AS, Santos MS, Almeida MB, Marín PJ, Silva DRP, Silva-Grigoletto MES. Inter-day reliability of the Upper Body Test for shoulder and pelvic girdle stability in adults. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy 2020;24:161-6. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2019.02.009 [Crossref]

- Koo TK, Li MY. A Guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2016;15:155-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012 [Crossref]

- Martin Bland J, Altman Douglas G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. The Lancet 1986;327:307-10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8 [Crossref]

- Harvey PD. Domains of cognition and their assessment. Dialogues in Clinical Neurosci. 2019;21:227-37. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2019.21.3/pharvey [Crossref]

- Collie A, Maruff P, Darby DG, McStephen M. The effects of practice on the cognitive test performance of neurologically normal individuals assessed at brief test–retest intervals. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;9(3):419-28. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703930074 [Crossref]

- Hoogendam YY, van der Lijn F, Vernooij MW, Hofman A, Niessen WJ, van der Lugt A, et al. Older age relates to worsening of fine motor skills: a population-based study of middle-aged and elderly persons. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00259 [Crossref]

- Park S-Y, Schott N. The trail-making-test: Comparison between paper-and-pencil and computerized versions in young and healthy older adults. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2022;29(5):1208-20. doi: 10.1080/23279095.2020.1864374 [Crossref]

- Miller JB, Barr WB. The technology crisis in neuropsychology. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2017;32:541-54. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acx050 [Crossref]

- Rumpf U, Menze I, Müller NG,

Schmicker M. Investigating the potential role of ecological validity on

change-detection memory tasks and distractor processing in younger and older

adults. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1046. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01046 [Crossref]

- Zanini GAV, Miranda MC, Cogo-Moreira H, et al. An Adaptable, open-access test battery to study the fractionation of executive-functions in diverse populations. Front Psychol. 2021;12:627219. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.627219 [Crossref]