Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc. 2024;23:e235581

doi: 10.33233/rbfex.v23i1.5581

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Capsaicin supplementation

enhances the physical performance of

kickboxing athletes

A suplementação de

capsaicina promove aumento no desempenho físico de atletas de kickboxing

Vernon Martins da Cruz,

Michel Efigênio Gonçalves, Rafael Henrique Nogueira, Matheus Dias Mendes,

Marcos Daniel Motta Drummond, Ronaldo Ângelo Dias da Silva

Universidade Federal de

Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil

Received: November 19,

2023; Accepted: January 18,

2024.

Correspondence: Marcos Daniel Motta Drummond, zangmarcos@gmail.com

How to

cite

Cruz VM, Gonçalves

ME, Nogueira RH, Mendes MD, Drummond MDM, Silva RAD. Capsaicin

supplementation enhances the physical performance of kickboxing athletes. Rev Bras Fisiol

Exerc. 2024;23:e235581. doi:

10.33233/rbfex.v23i1.5581

Abstract

Aim: The aim of the study

was to investigate

the acute effect of capsaicin

supplementation on the heart rate (HR), rate perception of effort

(RPE), and performance of

Kickboxing athletes undergoing

the Specific Kickboxing

Circuit Training Protocol (SKCTP). Methods: The sample consisted

of six black belt Kickboxing athletes (age

30.8 ± 6.47 years; height

1.76 ± 0.08 m; body mass 82.43 ± 28.03 kg; experience in the sport 13.71 ± 9.21 years). A randomized, cross-over, double-blind design was implemented in two separate sessions, one week apart. One session involved

12 mg of capsaicin supplementation (CAP), and the other involved

placebo supplementation (PLA). Results:

The Wilcoxon test revealed that the

total number of strikes thrown was significantly

higher (p = 0.03; d = 1.55) in the

capsaicin condition (369.14

± 12.10) compared to the Placebo condition (332.28 ±

31.23). The Friedman test demonstrated

that the first round in the CAP condition was superior to the three

rounds in the PLA condition,

and the second

round in CAP was superior to

the second and third rounds in PLA. No differences were observed in the HR mean between the

conditions (CAP = 132.42 ± 19.03 bpm and PLA: 133.57 ± 21.25 bpm; p = 0.87; d = 0.05) and in the RPE (CAP = 7.57 ± 1.51

and PLA = 7.00 ± 1.82; p = 0.43; d = 0.34). Conclusion: In conclusion,

acute capsaicin supplementation improved the performance of athletes in the SKCTP compared to the

placebo but did not show statistically significant differences in heart rate and subjective perceived exertion.

Keywords: sports nutritional science; dietary supplements; martial arts.

Resumo

Objetivo: O objetivo deste estudo foi investigar

os efeitos agudos da suplementação de capsaicina no desempenho físico de Kickboxers no Specific Kickboxing

Circuit Training Protocol (SKCTP), na frequência

cardíaca (FC) e na percepção subjetiva do esforço (PSE). Métodos: A

amostra foi composta por seis atletas faixas pretas de Kickboxing (idade 30,8 ±

6,47 anos; altura 1,76 ± 0,08 m; massa corporal 82,43 ± 28,03 kg; experiência

na modalidade de 13,71 ± 9,21 anos). O delineamento randomizado, cruzado e

duplo cego, foi aplicado em dois encontros separados por uma semana entre eles.

Um para a suplementação de capsaicina 12 mg (CAP) outro para a suplementação

Placebo (PLA). Resultados: O teste Wilcoxon

verificou que a quantidade total de golpes desferidos foi significativamente

maior (p = 0,03; d = 1,55) na condição CAP (369,14 ± 12,10) em comparação à

condição PLA (332,28 ± 31,23). O teste Friedman demonstrou que o primeiro round

da condição CAP foi superior aos três rounds PLA, e que o segundo round CAP foi

superior ao segundo e terceiro round PLA. Não foram verificadas diferenças na

frequência cardíaca média entre as condições (CAP: 132,42 ± 19,03 bpm e PLA:

133,57 ± 21,25 bpm; p = 0,87; d = 0,05) e na Percepção Subjetiva do Esforço

(CAP: 7,57 ± 1,51 e PLA: 7,00 ± 1,82; p = 0,43; d = 0,34). Conclusão:

Conclui-se que a suplementação aguda de capsaicina melhorou o desempenho dos

atletas no SKTCP em comparação ao Placebo, mas não apresentou diferenças para

FC e PSE.

Palavras-chave: ciências da nutrição e do esporte;

suplementos nutricionais; artes marciais.

Introduction

Kickboxing

is a combat sport discipline in which competitors aim to overcome their

opponent by scoring points through strikes or technical knockout, using hands, elbows,

knees, shins, and feet [1]. This

is an intermittent

characteristic sport

discipline, which can consist of 3 to

12 rounds lasting 2 to 4

minutes, with a rest period between 1 to 2 minutes between rounds [1]. Therefore, it is necessary for practitioners to develop physical

abilities such as cardiorespiratory endurance, strength, power, and agility, in addition to refining

technical and tactical elements [2,3].

Upon analyzing official competitions in the discipline, three distinct phases were identified during the match: a) high-intensity offensive and defensive actions;

b) low-intensity actions, preparation, and observation; and c) referee pause

[4]. Therefore, in order to analyze the

time-motion performance based

on the physical

demands of the discipline, it was developed the Specific

Kickboxing Circuit Training Protocol (SKCTP) [4]. Therefore, the SKCTP can be used

as a training tool and/or a

test for assessing the physical performance of Kickboxers, exposing them to

an effort-rest ratio and technical

execution similar to official matches [4].

Seeking better results in training and competitions, various nutritional ergogenic resources are used by practitioners in various sports modalities [5]. Among them, Capsaicin, a substance found in peppers, has been

extensively investigated in

the literature in various contexts [6]. The capsaicin interacts with the transient

receptor potential vanilloid

1 (TRPV1) receptor, located in the

sarcoplasmic reticulum [6],

which promotes greater release of calcium, consequently enhancing the interaction

between actin and myosin filaments,

leading to increased performance during physical exercise [6,7]. Furthermore, another explanation for the performance enhancement may be the potential

analgesic effect of capsaicin when

interacting with TRPV1, which would increase

the discomfort threshold and reduce

the rate of perceived exertion (RPE) [6,8].

In the literature, it is reported that

12 mg of capsaicin administered 45 minutes before exercise may result

in performance improvement [6]. However,

the results from various studies

are still highly contradictory.

Researchers observed that capsaicin supplementation was able to enhance

strength training performance [9,10], decrease sprint time [11], and

improve running performance at different

distances [12], as well as reduce session rate of perceived exertion

(sRPE) in Crossfit [8]. In contrast

to these findings, other studies observed that capsaicin did not improve performance in strength training [13], Crossfit [14], exhaustion

runs [15], and long-distance

running [16].

Given the divergence in results presented in the literature evaluating capsaicin supplementation in physical performance [9,10,12,13,14] and

the potential benefits of using

this supplement in combat sports, this study is

necessary. Therefore, the objective of

this study was to investigate

the acute effects of capsaicin

supplementation on the physical performance of Kickboxers, measured by the

total number of strikes performed in the SKCTP, heart rate (HR), and RPE. Moreover, based on the available

literature regarding the benefits of

Capsaicin, it is expected that athletes

will improve performance in SKCTP, reducing HR and RPE.

Methods

Ethical considerations

All procedures adopted

and the purpose

of the research

were explained to the athletes,

as well as the possible risks and benefits. The athletes read and

signed the Informed Consent Form. This project complied

with all the rules established

by the National

Health Council (Resolution

466/2012). The research in question

was submitted and approved by

the Ethics and Research Committee

of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (number: 5.683.532).

Sample

Six

black-belt Kickboxing athletes

participated in the study (age: 30.8 ± 6.47 years; height: 1.76 ± 0.08 m; body mass:

82.43 ± 28.03 kg), competing at

the regional and national levels, with a mean experience

of 13.71 ± 9.21 years in the sport. Body mass and height

were measured using a Líder P-180c scale with an attached

stadiometer (maximum capacity of 180 kg and minimum of

2.1 kg; precision of 0.1 kg

and 0.5 cm).

Athletes included in the study did

not consume any pre-training nutritional supplements, thermogenic substances, spicy foods, ginger, coffee, teas, alcohol, narcotics, or any

stimulating substances before training sessions. Exclusion criteria included athletes with injuries to the upper and

lower limbs or any other

medical conditions that could interfere with the tests.

Study design

Respecting the randomized, crossover, and double-blind design, carried out through the draw

of even numbers

for Placebo and odd numbers for Capsaicin, athletes performed two sessions of

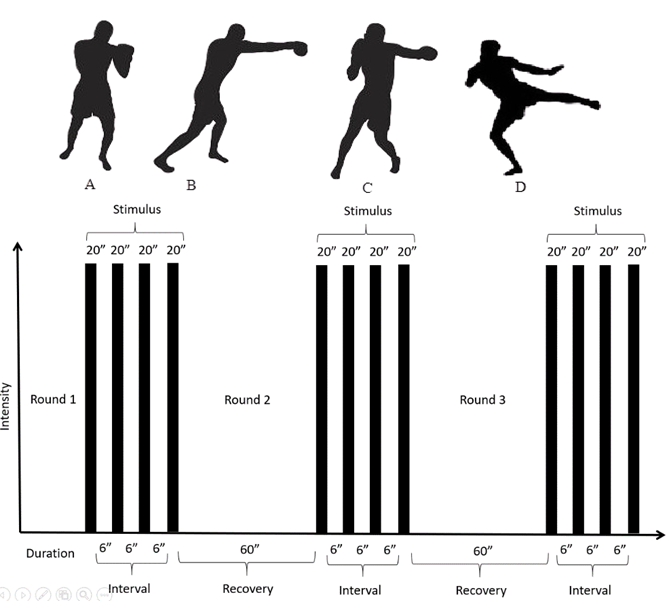

the SKCTP, with a one-week interval between them. The SKCTP consists of strike sequences of straight punch, cross punch,

and thigh-level kick (Low kick)

on a punching bag. Three rounds of 4 sets were performed, with a duration of 20 seconds of

stimulus (all out) per 6 seconds of interval

between sets and 60 seconds of rest

between rounds [4]. Additionally,

during the execution of the

SKCTP, average heart rate

(HR) was measured, and at the

end, the rating of perceived exertion

(RPE). Figure 1 below illustrates

the techniques employed and the

effort-rest relationship of the SKCTP.

Tests procedures

To tally the strikes performed in the SKCTP, athletes were filmed using

an Apple smartphone, iPhone 7 model (128 GB), mounted on a tripod

set in a vertical position at a distance

of 4 meters, so as not to

interfere with the athletes' execution of the strikes. The videos were analyzed

by the same

evaluator, who was blinded to

the experimental condition.

The footage was watched a minimum of 2 times and up to 3 times if

there was a difference in the strike count. For the execution of the

SKCTP, athletes used their usual training equipment to strike against a 25 kg punching bag suspended 150 cm above the ground.

To ensure that athletes started

and finished the sequence of

strikes respecting the pre-defined times of the protocol, a mobile application (Tabata Timer: Interval

Timer, developer: Eugene Sharafan)

was used, emitting a specific audible signal for each time interval.

The Heart

rate was measured pre and post-SKCTP using the Polar H10 heart rate monitor (Polar H10, Polar Electro Brazil, Ltda). The rate of perceived exertion was collected immediately

at the end

of the SKCTP protocol using the (CR-10) scale, ranging from 0 (rest) to 10 (maximum

effort) [17].

Capsaicin supplementation

During the testing sessions, through the random

assignment of even numbers (Placebo) and odd numbers

(Capsaicin), athletes consumed the substances

in a random and blinded manner, in identical capsules obtained from a compounding pharmacy, following specifications provided by an experienced

nutritionist. The Placebo capsule contained

50 mg of starch, while the capsaicin

capsule contained 12 mg. This

capsaicin dosage was chosen due

to its effectiveness in improving physical performance

[9,10,11,12], with no reported occurrences of side effects [13].

After supplement ingestion, a 45-minute interval was observed between

capsule intake and the start of the

testing protocol. This was done

to ensure that the tests

began at the peak concentration

moment of capsaicin following supplementation [6,9].

A = Start;

B = Direct Punch; C = Cross Punch; D = Low Kick.

Figure 1 – Strikes sequence

and effort-rest ratio in SKTCP

Statistical analysis

The data normality was assessed

using the Shapiro-Wilk

test. To compare the total number of strikes performed in the SKCTP, HR, and RPE between the capsaicin and

Placebo conditions, the Wilcoxon test was

applied. The Friedman test was used to

compare the number of strikes performed in each round. Cohen's d was employed to

assess the effect size (small

= 0.2 - 0.3; medium = 0.5 - 0.8; large

> 0.8). The significance level

adopted was α = 0.05. Statistical analysis was conducted using

the SPSS software (version

20.0).

Results

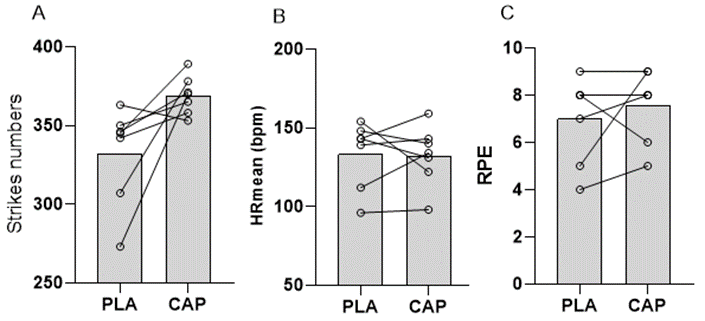

The total

number of strikes was significantly higher (t = 2.65, p = 0.03, d = 1.55) in the capsaicin condition

(369.14 ± 12.10) compared to

the Placebo condition

(332.28 ± 31.23). The mean HR showed

no statistically significant

difference (t = -0.16, p = 0.87, d = 0.05) in the capsaicin condition

(132.42 ± 19.03 bpm) when compared

to the Placebo condition (133.57 ± 21.25 bpm). The RPE did

not exhibit a statistically significant difference (t = 0.83, p = 0.43, d = 0.34) in the capsaicin condition

(7.57 ± 1.51) compared to the Placebo condition (7.00 ±

1.82). Figure 2 presents the

values of the total number of strikes delivered, HR, and RPE in the capsaicin and Placebo conditions.

PLA:

=Placebo; CAP = Capsaicina. *statistical significance p ≤ 0,05

Figure 2 - A = strikes numbers

in Specific Kickboxing Circuit Training Protocol. B = heart rate mean; C: rate of perceived exertion

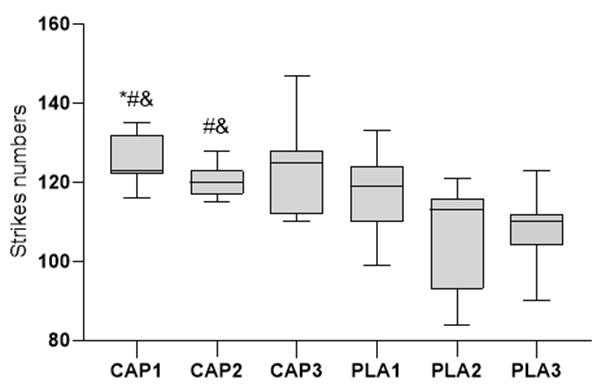

The number of strikes per round was significantly higher in the first

CAP round (125.71 ± 6.58) when compared

to the first

(117.57 ± 10.95, p = 0.02, d = 0.90), second (106.86

± 13.46, p = 0.01, d = 1.77), and third

PLA round (107.86 ± 10.02, p = 0.01, d = 2.10). The second

CAP round (120.43 ± 4.24) was not

significantly different from the first

PLA round (p = 0.60, d = 0.34). However, it was significantly higher than the

second (p = 0.04, d = 1.35) and

third PLA round (p = 0.02, d = 1.63). The third CAP round (123.00 ± 12.94) did

not differ from the first

(p = 1.00, d = 0.45), second (p = 0.14, d = 1.22), or third PLA round (p = 0.06, d =

1.30). Figure 3 below illustrates

these results.

*Statistical significance compared to PLA1. # statistical significance compared to PLA2. & statistical significance compared to PLA3

Figure 3 – Strikes numbers

in Specific Kickboxing Circuit Training Protocol on firts,

second and third rounds CAP (CAP1, CAP2 e CAP3) e PLA (PLA1, PLA2 e

PLA3)

Discussion

The aim of the present

study was to investigate the effect of

capsaicin supplementation on the physical

performance of Kickboxing athletes.

The formulated hypothesis was that capsaicin

would improve performance in the

SKCTP, and that HR and RPE would be

lower in the capsaicin condition. The results found in this study show that the total number of strikes delivered was higher

in the capsaicin condition compared to the Placebo. However, there was no significant difference in HR and RPE.

To the extent of our

knowledge, this was the first

study that assessed the performance of Kickboxing athletes in a specific test of

the modality using capsaicin supplementation. We are not aware of

other studies that evaluated capsaicin supplementation in specific tests in other combat sports,

which limits our discussion.

In the study by

Freitas et al. [9], an increase

in the total load (number of repetitions

x mass) was observed in a protocol of 4 sets of repetitions

to muscular failure, with an intensity

of 70% 1RM, a 90-second rest,

in the squat exercise when supplemented

with Capsaicin. Results from other

studies indicate that a dosage of

12 mg of capsaicin was able to

reduce the time in

1500-meter sprints in physically active

adults [11] and time to exhaustion by

13% in a high-intensity interval

training protocol [10]. Supporting

these findings, Costa et

al. [12] report that acute capsaicin supplementation also significantly improved

performance in the 400 meters

and 3000 m time trial in trained individuals.

In the present study,

capsaicin supplementation increased the strikes within the same

time frame in a specific test

of the sport.

This increase occurred with greater

magnitude in the first

round of the CAP condition compared to the three

rounds of the PLA situation, and in the second round of the CAP condition

compared to the second and

third rounds of the PLA condition. Therefore, it is expected that in a match, capsaicin supplementation could increase the probability of victory by

points and/or knockout for the athlete who

imposes a higher number of strikes. However, studies evaluating this hypothesis need to be conducted.

A possible explanation for the previously reported results is that capsaicin

may increase the activation of the TRPV1 receptor in skeletal muscle and enhance calcium

release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, influencing greater force production [18]. Additionally, another acute ergogenic

effect of capsaicin is its ability to stimulate

substrate oxidation, increase lipolysis, and spare more muscle glycogen [19,20], which would reduce

fatigue in long-duration and/or high-intensity activities where muscle glycogen is crucial for performance.

The muscle glycogen-sparing effect promoted by capsaicin can

contribute to Kickboxers, considering the effort-rest ratio, energy demands,

and physical fitness that are crucial for success in the sport [2]. However, Opheim and Rankin [21] did not observe difference in the performance of athletes subjected

to 15 sets of 30-meter

sprints with 30 seconds of rest in the

condition of 25.8 mg of capsaicin for 7 days. The difference between the results

of the study

by Opheim and Rankin [21] and the present

study may be due to

the chosen training protocol and the

administered dosage.

Gastrointestinal discomfort was

reported in the study by Opheim

and Rankin [21], which may have

affected the results.

Freitas et

al. [9] and Freitas et al. [11] also assessed the

effects of capsaicin supplementation on the RPE, which

was measured immediately after each set in strength training and at the

end of the

1500m run, respectively. These authors found

improvement in performance and

lower RPE values in the capsaicin condition

compared to the Placebo condition. Additionally, Piconi et al.

[8] also observed a decrease in session RPE after a Crossfit training protocol.

The authors attribute the lower RPE values

to the potential

analgesic effect of capsaicin [6], which could increase

the discomfort threshold. However, the present study

did not find

a decrease in RPE in Kickboxers

undergoing a specific test when supplemented

with Capsaicin. Consistent with the findings of

the present study, Piconi et al. [14] showed no significant difference in session RPE among female Crossfit competitors between the capsaicin and

Placebo conditions. The differences

between the results of these

studies may be justified by

the characteristics of the sports

demand and possibly by the

motivational aspect in the execution of

the task among athletes and practitioners of different modalities

when performing general exercises and specific

tests. However, motivational aspects were not assessed

in these studies, presenting a limitation for discussing these results.

The findings of these

studies [9,11,13,14] suggest

that the type of exercise

is an important

factor regarding the benefits of

capsaicin supplementation.

It appears that this substance may have an

ergogenic role according to the duration

of the exercise,

benefiting exercises that rely heavily

on glycolysis [6,12], as is the case with

Kickboxing [2,3,4,22].

It is important to

note that this study has some limitations, such as a small sample size, the absence of

general tests that assess other physical

demands inherent to the modality,

the application of a side effects

questionnaire, and the measurement of lactate concentration

to better characterize the energy demand in the test.

Conclusion

Acute capsaicin supplementation increased the total number of strikes executed by Kickboxing athletes in a specific modality test. However, there were no statistically significant differences in heart rate and rate of perceived exertion

between the supplemented conditions.

Conflict of Interest

The

authors declare no conflict

of interest.

Financing

This study

is self-funded.

Authors’ contribution

Conception and study design: Cruz

VM, Gonçalves ME, Drummond MDM, and Silva RAD; Data

acquisition: Cruz VM, Gonçalves ME, Nogueira RH,

Mendes MD, Silva RAD; Data analysis and interpretation: Cruz VM,

Gonçalves ME, Nogueira RH, Mendes MD, and Silva RAD; Statistical analysis:

Cruz VM, Nogueira RH, Mendes MD, and Silva RAD; Manuscript writing: Cruz VM,

Gonçalves ME, Silva RAD; Critical manuscript revision for important intellectual content: Cruz VM, Drummond MDM, and

Silva RAD.

References

- Dugonjić B,

Krstulović S, Kuvačić G.

Rapid weight loss practices in elite Kickboxers. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab.

2019;29(6):583-88. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0400 [Crossref]

- Ouergui I, Hammouda

O, Chtourou H, Zarrouk N,

Rebai H, Chaouachi A. Anaerobic

upper and lower body power measurements and perception of fatigue during a kickboxing match. J Sports Med Phys

Fitness. 2013 Oct;53(5):455-60. PMID: 23903524

- Ouergui I, Hssin N,

Haddad M, Padulo J, Franchini E, Gmada

N, Bouhlel E. The effects of five weeks

of kickboxing training on physical fitness. Muscles Ligaments Tendons

J. 2014a;4(2):106-113. PMID: 25332919

- Ouergui I, Houcine N,

Marzouki H, Davis P, Zaouali

M, Franchini E, Gmada N, Bouhlel

E. Development of a noncontact kickboxing circuit

training protocol that simulates elite male kickboxing competition.

J Strength Cond

Res. 2015;29(12):3405-11. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001005 [Crossref]

- Kerksick CM, Wilborn

CD, Roberts MD, Smith-Ryan A, Kleiner SM, Jager R, et

al. Exercise & sports nutrition review update: research

& recommendations. J Int

Soc Sports Nutr. 2018;15(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12970-018-0242-y [Crossref]

- Moura e Silva VEL, Cholewa JM, Billaut F, Jager R, Freitas MC, Lira FS, et al. Capsaicinoid

and capsinoids as an ergogenic aid:

A systematic review and the potential mechanisms

involved. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2021;16(4):464-73. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2020-0677 [Crossref]

- Linari M, Brunello E, Reconditi

M, Fusi L, Caremani M, Narayanan T, et al. Force generation

by skeletal muscle is controlled

by mechanosensing in myosin filaments. Nature. 2015;528(7581):276-9. doi: 10.1038/nature15727 [Crossref]

- Piconi BS, Oliveira MP, Silva RAD, Drummond MDM. Efeito agudo da suplementação de capsaicina na percepção subjetiva de esforço de uma sessão em competidores de Crossfit. Brazilian Journal of Health Review. 2021;4(3):9742-9753. doi: 10.34119/bjhrv4n3-013 [Crossref]

- Freitas MC, Cholewa JM, Freire RV, Carmo BA, Bottan

J, Bratfich M, et al. Acute

capsaicin supplementation improves

resistance training performance in trained men. J Strength Cond Res.

2018a;32(8):2227-32. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002109 [Crossref]

- Freitas MC, Cholewa JM, Panissa VLG, Toloi GG, Netto HC, Freitas CZ, et al. Acute

capsaicin supplementation improved resistance exercise performance after a

high-intensity intermittent

running in resistance-trained men.

J Strength Cond

Res. 2019;36(1):130-34. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003431 [Crossref]

- Freitas MC, Cholewa JM, Gobbo LA, Oliveira JVNS, Lira FS, Rossi FE. Acute capsaicin supplementation improves 1,500-m running time-trial performance and rate of perceived exertion

in physically active adults. J Strength Cond Res. 2018b;32(2):572-77. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002329 [Crossref]

- Costa LA, Freitas MC, Cholewa JM, Panissa VLG, Nakamura FY, Silva VELM, et al. Acute capsaicin analog supplementation improves 400 m and 3000 m running time-trial performance. Int J Exerc Sci. 2020;13(2):755-65. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000560912.52618 [Crossref]

- Simões CB, Gomes PLC, Silva RAD, Fonseca ICS, Fonseca M, CRUZ VM, et al. Acute caffeine and capsaicin supplementation and performance in resistance training. Motriz. 2022;28. doi: 10.1590/S1980-65742022010121 [Crossref]

- Piconi BS, Oliveira MP, Silva RAD, Drummond

MDM. Suplementação de capsaicina e o desempenho de mulheres no crossfit.

Coleção Pesquisa em Educação Física. 2019;18(4):117-26.

- Padilha CS, Billaut F, Figueiredo C, Panissa VLG, Rossi FR, Lira FS. Capsaicin supplementation during high-intensity continuous exercise: A double-blind study. Int J Sports Med. 2020;41(14):1061-66. doi: 10.1055/a-1088-5388 [Crossref]

- von Ah Morano AEV, Padilha CS, Soares VAM, Machado FA, Hofmann P, Rossi FE, et al. Capsaicin analogue supplementation does not improve 10 km running time-trial performance in male amateur athletes: A randomized, crossover, double-blind and placebo-controlled study. Nutrients. 2021;13(1):34. doi: 10.3390/nu13010034 [Crossref]

- Foster C, Daines E, Hector L, Snyder Ac, Welsh R. Athletic

performance in relation to

training load. Wis Med J.

1996 Jun;95(6):370-74. PMID: 8693756

- Lotteau S, Ducreux S, Romestaing C, Legrand C, Coppenolle FV. Characterization of functional TRPV1 channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum of mouse skeletal muscle. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58673. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058673 [Crossref]

- Kim KM, Kawada

T, Ishihara K, Inoue K, Fushiki T. Increase in swimming endurance capacity of mice by

capsaicin-induced adrenal catecholamine

secretion. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1997;61(10):1718-23. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.1718 [Crossref]

- Hsu YJ, Huang WC, Chiu CC, Liu YL, Chiu WC,

Chiu CH, et al. Capsaicin supplementation

reduces physical fatigue and improves exercise performance

in mice. Nutrients.

2016;8(10):648. doi: 10.3390/nu8100648 [Crossref]

- Opheim MN, Rankin

JW. Effect of capsaicin supplementation on repeated sprinting

performance. J Strength Cond

Res. 2012;26(2):319-26. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182429ae5 [Crossref]

- Ouergui I, Hssin N, Haddad M, Franchini E, Behm Dg, Wong Dp, Gmada N, Bouhlel E. Time-motion analysis of elite male kickboxing competition. J Strength Cond Res. 2014b;28(12):3537-43. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000579 [Crossref]