Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc.

2024;23(3): e235594

OPINION

Physical fitness as a vital sign: why are we not using it in clinical

practice?

Aptidão física como

sinal vital: por que não a utilizamos na prática clínica?

Dahan da Cunha Nascimento,

Bruno Viana Rosa, Karla Helena Coelho Vilaça e Silva

Universidade Católica de

Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brazil

Received 2024 May 2; Accepted

2024 Oct 14

Correspondence: Dahan da Cunha Nascimento, E–mail: dahanc@hotmail.com

How to cite

Nascimento DC, Rosa BV, Silva

KHCV. Physical fitness as a vital sign:

why are we not using it in clinical practice? Rev Bras Fisiol

Exerc. 2024;23(3):e235594. doi:

10.33233/rbfex.v23i3.5594

Abstract

Physical inactivity can be considered a disease of the 21st century. Among

several physical parameters, strength and cardiorespiratory fitness stand out

as they are strongly associated with mortality and chronic diseases. Thus, we

propose that physical fitness can be used as a vital sign and that strength and

cardiorespiratory fitness can be applied to assess health in practice. This can

be accomplished using muscular strength cutoff points for the elderly, such as

< 32 kg for men and < 21 for women, using a manual dynamometer, and <

40% of body weight in isometric knee extension. Likewise, several maximal and

submaximal tests, such as a 12-minute running test or step test, can be used as

a low-cost alternative for assessing cardiorespiratory fitness. Therefore, the

assessment of physical fitness parameters can be a promising and low-cost

screening tool to identify participants at risk of disability, chronic

non-communicable diseases and survival prognosis.

Keywords: muscle strength; cardiorespiratory fitness; public

health

Resumo

A inatividade física pode

ser considerada como uma doença do século XXI. Dentre diversos parâmetros

físicos, a força e a aptidão cardiorrespiratória se destacam por estarem

fortemente associadas a mortalidade e doenças crônicas. Dessa forma, propomos

que a aptidão física possa ser utilizada como sinal vital e que força e aptidão

cardiorrespiratória podem ser aplicadas para avaliar a saúde na prática. Isso

pode ser realizado utilizando os pontos de corte de força muscular para idosos,

como < 32 kg para homens e < 21 para mulheres, com uso de dinamômetro

manual, e < 40% do peso corporal na extensão isométrica de joelho. Da mesma

forma, diversos testes máximos e submáximos, como teste de 12 minutos de

corrida ou teste de degrau, podem ser utilizados como alternativa de baixo

custo para avaliação de aptidão cardiorrespiratória. Portanto, a avaliação de

parâmetros da aptidão física podem ser ferramenta de triagem promissora e de

baixo custo para identificar participantes com risco de incapacidade, doenças

crônicas não transmissíveis e prognóstico de sobrevivência.

Palavras-chave: força muscular; aptidão

cardiorrespiratória; saúde pública

Introduction

Physical inactivity and sedentary behavior are the

diseases of the 21st century, which have been linked to chronic

non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, cancer,

and depression [1,2,3,4,5]. It is estimated that, between 2020 and 2023, 500 million

preventable NCDs will occur due to physical inactivity, with 47% being

attributed to hypertension and 43% to depression [6].

However, physical inactivity is still undervalued in

public health and clinical medicine and not given the same importance as

traditional risk factors such as hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and high

cholesterol [2].

It is crucial to consider evaluating components of

physical fitness such as cardiorespiratory, morphological, muscular, metabolic,

and motor in clinical practice. Traditionally, the American College of Sports

Medicine (ACSM) considers strength, flexibility, and cardiorespiratory fitness

as components of health-related physical fitness [7]. However, flexibility does

not seem to be an efficient predictor of cardio-metabolic health and mortality,

despite being beneficial for joint mobility [8].

On the other hand, low levels of muscle strength have

been identified as a predictor of all-cause mortality, functional,

psychological, and social health in the elderly population [9,10,11]. Similarly,

low levels of cardiorespiratory fitness increase the risk of cardiovascular

mortality, cancer mortality in men, and coronary heart disease in both sexes

[2,12,13].

Therefore, we propose the use of physical fitness

components as a vital sign and suggest how strength and cardiorespiratory

fitness can be applied to assess health in clinical practice.

Muscle strength as a vital sign

Muscle strength is a stronger predictor of death than

traditional risk factors such as systolic blood pressure [14]. Furthermore,

high levels of muscular strength are significantly associated with a lower risk

of all-cause mortality in hypertensive men, even after controlling for

potential confounders such as age, physical activity, smoking, alcohol intake,

body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol,

diabetes, abnormal electrocardiogram, family history of cardiovascular disease,

and cardiorespiratory fitness [14,15].

It is comprehensible that low levels of muscular strength

and cardiorespiratory fitness are independent predictors of cardiovascular

hospitalizations, mortality due to suicide, and all-cause mortality.

Furthermore, hospital costs are approximately 20% more expensive in patients

with lower strength, even after controlling for factors such as malnutrition,

patient characteristics, and disease severity [16].

Therefore, the use of cut-off points already displayed in

the scientific literature should be included in clinical practice for older

participants, adults, and children. For older participants, a handgrip strength

of less than 32 kg for men and less than 21 kg for women has been found to be

the best probability of identifying mobility limitations among older adults in

Brazil [17].

However, for measuring mobility, it seems more intuitive

to measure lower limb strength as it has a lower correlation with physical

performance tests related to mobility and a low correlation with handgrip

strength and low correlation with lower limb strength [18,19,20,21,22]. This low

correlation is due to the fact that the lower limb has a greater loss of

strength when compared to the upper limb [23].

Therefore, the test of sitting and standing up from a

chair can be used, as the inability to perform the test or taking more than 15

seconds to complete the test is a good indicator of mobility limitation [24].

Another possibility is to verify isometric knee extension strength, as having a

strength of 40% of body weight (sensitivity was 85.7% and specificity was

82.4%) is a reliable target to verify independence of older participants to

rise from a chair without using upper limbs [25].

In addition to the elderly, populations of other ages,

such as children, adolescents and adults, also have reference values for muscle

strength proposed by several studies [26]. However, for children, studies are

even more necessary to identify reference values normalized by body mass or

height, as these parameters are the ones that most influence the muscular

strength of this population and not necessarily age [27].

Furthermore, it is already established that low strength

in the elderly and adults is a risk factor for mortality from all causes, but

there are few longitudinal studies to show how low strength in childhood and

adolescence could harm you throughout your life.

Cardiorespiratory fitness as a vital sign

Cardiorespiratory fitness is normally measured through VO2max, which is the maximum

capacity to capture, transport and use oxygen [28]. It is an extremely important

measure for cardiovascular health,

being independently associated with mortality from all causes, cancer, and heart disease.

An increase of one metabolic equivalent (MET) in VO2max can reduce the risk

of coronary heart disease by 13% and 15% [29].

There are several ways to measure cardiorespiratory

fitness, the gold standard being ergospirometry - the maximum effort is

performed using a portable gas analyzer [7]. However, this material involves

high cost and specialized human material; indirect tests can offer a valid and

alternative way of measuring VO2max. Therefore, several maximum or submaximal

tests, which generally associate a certain oxygen consumption with a load,

heart rate or time, can be used for this purpose [30].

Among these tests, the 12-minute field tests (r = 0.79;

0.73-0.85) and 2400 m (r = 0.78, 0.72-0.83) have good validity and are

practical and cheap to be used on a daily basis by adults and children [28]. For the elderly, submaximal step tests, treadmill, or cycle ergometer

can be used

[31].

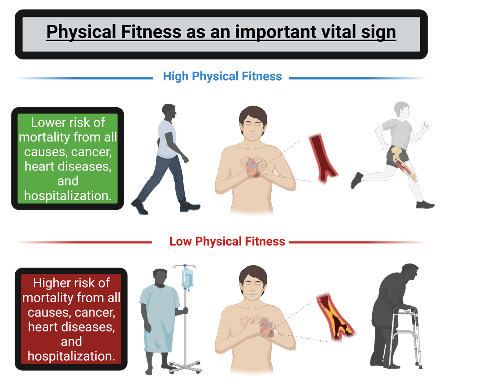

Conclusion

Thus, this opinion article raises the concern of not

utilizing the components of physical fitness, such as muscular strength and

cardiorespiratory fitness, in clinical medicine and clinical practice (Figure

1). These components can be used as a promising screening tool to identify

participants at risk of disability, NCDs, and survival prognosis

Created in

https://BioRender.com

Figure 1 - Physical fitness as an important vital sign

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Sources of funding

There was no funding.

Authors' contributions

Conception and design of the research: Nascimento DC; Manuscript writing: Nascimento DC; Critical

revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Rosa BV,

Silva KHCV

References

- Arocha Rodulfo

JL. Sedentary lifestyle a disease from XXI century. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2019;31(5):233-40. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1304982 [Crossref]

- Blair SN. Physical inactivity: the biggest public health problem of the

21st century. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(1):1-2.

- Milton K, Gomersall SR, Schipperijn J. Let's get moving: The Global Status Report on Physical Activity 2022 calls for urgent action. J Sport Health Sci. 2023;12(1):5 doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2022.12.006 [Crossref]

- Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Stracciolini A, Hewett TE, Micheli LJ, Best TM. Exercise deficit disorder in youth: a paradigm shift toward disease prevention and comprehensive care. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2013;12(4):248-55. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31829a74cd [Crossref]

- Myers J, Prakash M, Froelicher V, Do D, Partington S, Atwood JE. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(11):793-801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011858 [Crossref]

- Organization WH. Global status report on physical activity 2022: World

Health Organization; 2022.

- Medicine ACoS.

Manual do ACSM para avaliação da aptidão física relacionada à saúde: Grupo Gen-Guanabara Koogan; 2011.

- Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, Fiatarone Singh MA, Minson CT, Nigg CR, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(7):1510-30. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a0c95c [Crossref]

- Carbone S, Kirkman DL, Garten RS, Rodriguez-Miguelez P, Artero EG, Lee DC, et al. Muscular Strength and Cardiovascular Disease: an updated state-of-the-art narrative review. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2020;40(5):302-9. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000525 [Crossref]

- Ling CH, Taekema D, de Craen AJ, Gussekloo J, Westendorp RG, Maier AB. Handgrip strength and mortality in the oldest old population: the Leiden 85-plus study. CMAJ. 2010;182(5):429-35. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091278 [Crossref]

- Newman AB, Kupelian V, Visser M, Simonsick EM, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, et al. Strength, but not muscle mass, is associated with mortality in the health, aging and body composition study cohort. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(1):72-7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.1.72 [Crossref]

- Lee CD, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness and smoking-related and total cancer mortality in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(5):735-9. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200205000-00001 [Crossref]

- Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, Labayen I, Lavie CJ, Blair SN. The Fat but Fit paradox: what we know and don't know about it. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(3):151-3. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097400 [Crossref]

- Leong DP, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Avezum A, Jr., Orlandini A, et al. Prognostic value of grip strength: findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. Lancet. 2015;386(9990):266-73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62000-6 [Crossref]

- Artero EG, Lee DC, Ruiz JR, Sui X, Ortega FB, Church TS, et al. A prospective study of muscular strength and all-cause mortality in men with hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(18):1831-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.025 [Crossref]

- Guerra RS, Amaral TF, Sousa AS, Pichel F, Restivo MT, Ferreira S, et al. Handgrip strength measurement as a predictor of hospitalization costs. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(2):187-92. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.242 [Crossref]

- Delinocente MLB, de Carvalho DHT, Maximo RO, Chagas MHN, Santos JLF, Duarte YAO, et al. Accuracy of different handgrip values to identify mobility limitation in older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2021;94:104347. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2021.104347 [Crossref]

- Harris-Love MO, Benson K, Leasure E, Adams B, McIntosh V. The Influence of Upper and Lower Extremity Strength on Performance-Based Sarcopenia Assessment Tests. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2018;3(4):53. doi: 10.3390/jfmk3040053 [Crossref]

- Martien S, Delecluse C, Boen F, Seghers J, Pelssers J, Van Hoecke AS, et al. Is knee extension strength a better predictor of functional performance than handgrip strength among older adults in three different settings? Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60(2):252-8. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.11.010 [Crossref]

- Bohannon RW. Dynamometer measurements of grip and knee extension strength: are they indicative of overall limb and trunk muscle strength? Percept Mot Skills. 2009;108(2):339-42. doi: 10.2466/PMS.108.2.339-342 [Crossref]

- Felicio DC, Pereira DS, Assumpcao AM, de Jesus-Moraleida FR, de Queiroz BZ, da Silva JP, et al. Poor correlation between handgrip strength and isokinetic performance of knee flexor and extensor muscles in community-dwelling elderly women. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14(1):185-9. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12077 [Crossref]

- Rodacki ALF, Boneti Moreira N, Pitta A, Wolf R, Melo Filho J, Rodacki CLN, et al. Is handgrip strength a useful measure to evaluate lower limb strength and functional performance in older women? Clin Interv Aging. 2020;15:1045-56. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S253262. eCollection 2020 [Crossref]

- Samuel D, Wilson K, Martin HJ, Allen R, Sayer AA, Stokes M. Age-associated changes in hand grip and quadriceps muscle strength ratios in healthy adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24(3):245-50. doi: 10.1007/BF03325252 [Crossref]

- Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB, Simonsick EM, Harris TB, Penninx BW, et al. Added value of physical performance measures in predicting adverse health-related events: results from the Health, Aging And Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(2):251-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02126.x [Crossref]

- Bohannon RW. Body weight-normalized knee extension strength explains sit-to-stand independence: a validation study. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(1):309-11. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31818eff0b [Crossref]

- Benfica PDA, Aguiar LT,

Brito SAF, Bernardino LHN, Teixeira-Salmela LF, Faria

C. Reference values for muscle strength: a systematic review with a descriptive meta-analysis. Braz J

Phys Ther.

2018;22(5):355-69. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2018.02.006 [Crossref]

- McKay MJ, Baldwin JN, Ferreira P, Simic M, Vanicek N, Burns J, et al. N [Crossref]ormative reference values for strength and flexibility of 1,000 children and adults. Neurology. 2017;88(1):36-43. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003466 [Crossref]

- Taylor HL, Buskirk E, Henschel A. Maximal oxygen intake as an objective measure of cardio-respiratory performance. J Appl Physiol. 1955;8(1):73-80. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1955.8.1.73 [Crossref]

- Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, Maki M, Yachi Y, Asumi M, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301(19):2024-35. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.681 [Crossref]

- Mayorga-Vega D, Bocanegra-Parrilla R, Ornelas M, Viciana J. Criterion-related validity of the distance- and time-based walk/run field tests for estimating cardiorespiratory fitness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151671 [Crossref]

- Smith AE, Evans H, Parfitt G, Eston R, Ferrar K. Submaximal exercise-based equations to predict maximal oxygen uptake in older adults: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(6):1003-12. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.09.023 [Crossref]