Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc.

2024;23(3):e235618

REVIEW

Pain and movement: practical assessment methods for health and exercise

professionals

Dor e movimento:

métodos práticos de avaliação para profissionais da saúde e do exercício

Poliana de Jesus Santos,

Lara Fabian Vieira Barbosa, José Carlos Aragão-Santos, Marcos Raphael

Pereira-Monteiro, Marzo Edir Da Silva-Grigoletto

Universidade Federal de

Sergipe, São Cristovão, SE, Brasil

Received 2024 november 8th; accepted 2024 10th December

Correspondence: Poliana de Jesus Santos, polianadejsantos@gmail.com

How to cite

Poliana de Jesus Santos PJ, Lara

Fabian Vieira Barbosa LFV, José Carlos Aragão-Santos JC, Marcos Raphael

Pereira-Monteiro MR, Marzo Edir Da Silva-Grigoletto

ME. Pain and movement: practical assessment methods for health and exercise

professionals. Rev Bras Fisiol Exerc. 2024;23(3);e235618. doi:

10.33233/rbfex.v23i3.5618

Abstract

Pain is an unpleasant experience that affects almost the entire world

population at some point in life. While acute pain serves as a protective

mechanism, chronic pain negatively impacts individuals' physical fitness,

social and psychological aspects, leading to high levels of absenteeism and

reduced productivity, thus becoming a global health issue. There are several

treatment options for chronic pain, with physical exercise being the most

recommended. However, to obtain the benefits of physical exercise in pain

reduction, it is necessary to understand the factors that may be related to or

interfere with the pain phenomenon. Likewise, it is essential to recognize that

each individual responds differently to this phenomenon. In this context, a

detailed pain assessment is required. Proper evaluation will allow movement

professionals, such as physical education instructors, physiotherapists, and

other health professionals, to act more efficiently in managing pain through

physical exercise. Nevertheless, pain assessment can sometimes be complex or

costly, limiting its use in professional practice. Therefore, the present study

seeks to present and discuss practical, low-cost methods for multidimensional

pain assessment and highlight important concepts in pain management. Hence,

this article will serve as a starting point for movement professionals in

managing pain through practical and cost-effective methods.

Keywords: assessment, pain; quality of life; professional

competence; physical exercise

Resumo

A

dor é uma experiência

desagradável que aflige quase toda a população

mundial em algum momento da

vida. Apesar da dor aguda servir como mecanismo de

proteção, a dor crônica

afeta negativamente a aptidão física, os aspectos sociais

e psicológicos dos

indivíduos, resultando em altos níveis de absentismo no

trabalho e diminuição

da produtividade, tornando-se um problema de saúde mundial.

Existem várias

opções de tratamento para a dor crônica e o

exercício físico é a opção mais

recomendada. No entanto, para a obtenção dos

benefícios do exercício físico na

redução da dor é preciso compreender os fatores

que podem estar relacionados

e/ou interferindo no fenômeno da dor. De igual forma, é

essencial entender que

cada indivíduo responde de uma maneira diferente a esse

fenômeno. Nesse

contexto, é preciso realizar uma avaliação

detalhada da dor. Uma avaliação

adequada permitirá aos profissionais do movimento, tais como

profissionais de

educação física, fisioterapeutas e outros

profissionais da saúde, atuarem de

forma mais eficiente no manejo da dor por meio do exercício

físico. Contudo,

por vezes a avaliação da dor pode ser muito complexa ou

de alto custo

dificultando sua utilização na prática

profissional. Portanto, o presente

estudo busca apresentar e discutir métodos práticos e de

baixo custo para a

avaliação da dor de modo multidimensional, bem como

destacar conceitos

importantes no tratamento da dor. Desta forma, esse artigo será

um ponto de

partida para a atuação dos profissionais do movimento no

manejo da dor por meio

de métodos práticos e de baixo custo.

Palavras-chave: avaliação, dor; qualidade de vida;

competência profissional; exercício físico

Resumen

El dolor

es una experiencia desagradable que afecta a casi toda la población mundial en algún momento de la vida. Aunque el dolor agudo actúa como un mecanismo de protección, el dolor crónico impacta negativamente en

la aptitud física y en los aspectos sociales y psicológicos de los individuos, lo cual se traduce en altos niveles de absentismo laboral y disminución de la productividad, convirtiéndose en un problema de salud mundial. Existen varias opciones de tratamiento para el dolor crónico, siendo el ejercicio

físico la opción más

recomendada. Sin embargo, para obtener

los beneficios del ejercicio físico en la reducción

del dolor, es necesario comprender los factores que pueden estar relacionados y/o interferir en el fenómeno del dolor. Asimismo,

es esencial entender que cada individuo

responde de manera diferente a este fenómeno. En este contexto, es necesaria

una evaluación detallada del dolor. Una evaluación adecuada permitirá a los profesionales del movimiento, tales como

licenciados en ciencia de la actividad física y del deporte, fisioterapeutas y otros

profesionales de la salud, actuar de manera más eficiente en el manejo del dolor

mediante el ejercicio

físico. Sin embargo, a veces

la evaluación del dolor puede

ser compleja o de alto costo,

lo que dificulta su aplicación en la

práctica profesional. Por lo tanto, el presente estudio busca presentar y discutir métodos prácticos y de bajo costo para la evaluación del

dolor de forma multidimensional, así

como destacar conceptos importantes en el tratamiento del dolor. De este modo, este

artículo busca serun punto

de partida para la actuación

de los profesionales del movimiento en el manejo del

dolor a través de métodos prácticos

y de bajo costo.

Palabras-clave: evaluación, dolor;

calidad de vida; competencia

profesional; ejercicio

físico

Introduction

The International Association for the Study of Pain

(IASP) defines pain as "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience

associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue

damage" [1]. Pain can be temporally classified as either acute or chronic.

Chronic pain is defined as pain persisting for more than three months beyond

the typical healing time for an injury or associated with chronic pathological

processes that result in continuous or recurrent pain. Studies indicate that the

global prevalence of chronic pain is 53% [2], and in Brazil, this prevalence

stands at 45.59%, with the lower back being the most affected area [3].

Chronic pain impacts not only physical fitness but also

social and psychological aspects of an individual's life. Among people

reporting chronic pain, high levels of work absenteeism and decreased

productivity have been observed [4]. Given the high prevalence of chronic pain,

it is reasonable to expect significant economic repercussions. Furthermore,

individuals with chronic pain have been found to be twice as likely to report

suicidal behaviors or to die by suicide [5], underscoring the impact of chronic

pain on mental health. Despite these consequences, pain is often overlooked in

the context of assessing an individual's health status. Nevertheless, certain

interventions can provide a better experience for those suffering from

pain-related distress, facilitating decision-making and leading to improved

outcomes [6].

However, some movement professionals still seem to

underestimate the impact of pain when interacting with clients and patients.

This may be due to factors such as a lack of knowledge about pain assessment

methods [7] and the normalization of pain during physical exercise. This

tendency to normalize pain, along with the lack of professional conduct

adjustments in response to this condition, results in decreased engagement with

these professionals among individuals suffering from chronic pain [8]. Consequently,

this leads to a lack of awareness of the beneficial effects of physical

exercise on pain management among some of these professionals. Interestingly,

the same professionals who sometimes normalize pain are also responsible for

one of the most scientifically supported non-pharmacological interventions for

pain reduction: physical exercise [9,10,11].

For movement professionals to effectively promote health

and reduce pain through exercise, it is essential to conduct a holistic

assessment of the condition of the client or patient, including pain assessment

to guide professional conduct and provide indicators for medium- and long-term

follow-up [12]. Immediately, pain assessment can help to identify movement

patterns that the client or patient may alter or even avoid due to pain.

Additionally, baseline assessment values enable the professional to monitor whether

pain increases or decreases in response to the adopted approach. In cases where

pain worsens, a "fear-avoidance" cycle often occurs, leading to the

cessation of exercise due to past painful experiences, which may foster

limiting beliefs [13].

Despite the challenges discussed, exercise remains the

primary approach for treating chronic pain [14] and is also the main tool used

by movement professionals. Mechanisms such as exercise-induced hypoalgesia

reduce pain intensity and enhance the quality of life for individuals with

chronic pain [15]. However, studies show that participants in various exercise

modalities — such as Pilates, weight training, martial arts, CrossFit, body

jump, and others — who are guided by movement professionals exhibit high rates

of pain incidence, regardless of regular exercise practice [16,17,18,19]. This may

stem from underlying biomechanical or social factors that are inadequately

assessed. Thus, it becomes necessary for these professionals to incorporate

pain assessment in their approach. This ensures that regular physical exercise

promotes pain reduction and encourages individuals to see exercise as an

effective approach to pain management, alongside its numerous health benefits.

Considering the impact of chronic pain, the potential of

physical exercise in its treatment, and the limited use of pain assessment

methods among movement professionals, this study aims to present and discuss

practical, low-cost methods for multidimensional pain assessment tailored to

movement professionals. Additionally, it highlights pain-related concepts and

mechanisms, consolidating existing literature into an accessible,

reader-friendly narrative review.

Pain is a response to noxious stimuli that threaten

tissues or the organism's survival, alerting the body to protect the tissue

from damage. These noxious stimuli typically stem from extreme pressure and/or

temperatures, potentially resulting in tissue damage. Pain pathways form a

complex and dynamic system encompassing sensory, cognitive, and behavioral

aspects [20].

The noxious stimulus is initially detected by peripheral

neurons called nociceptors, which transmit the nociceptive stimulus to the

central nervous system (CNS) [21]. Pain-related nerve fibers are classified

into two types: Ad and C fibers. Ad fibers are larger in diameter and myelinated, resulting

in faster conduction speeds and typically associated with acute or sharp pain.

Conversely, C fibers have slower conduction speeds, smaller diameters, and are

unmyelinated associating them more with prolonged nociceptive stimuli, as in

cases of chronic pain [21,22].

Among the ascending pain pathways, the spinothalamic

pathway stands out for its role in the sensory-discriminative aspects of the

pain experience, including the identification of location, intensity, and type

of pain stimulus. Meanwhile, the spinoreticular pathway, connected to the

amygdala, is associated with more diffuse pain and the affective properties of

pain [23]. These pathways are vertically located along the ventrolateral

portion of the spinal cord and transmit pain, temperature, and deep pressure stimuli

to the thalamus [24]. Once reaching the thalamus, the nociceptive stimulus is

directed to other brain areas, such as the cortex, for processing, which

results in pain perception [25].

After processing a painful stimulus, the brain can

modulate pain through descending mechanisms, producing an analgesic effect

during the pain process. In the gray matter region of the brain, a pain

inhibition system is activated via its connection with the ventromedial nucleus

of the spinal cord, a process mediated by opioids. This structure is involved

in both pain inhibition and facilitation [26]. Literature suggests that an

imbalance between the ascending and descending pain pathways may lead to a pathological

and continuous pain process, initiating chronic pain [27].

Another mechanism related to the pain experience is

temporal summation (TS), which mainly affects C fibers. TS increases the

activity of second-order neuron receptors, resulting in increased pain,

particularly present in cases of chronic pain [28]. TS is thought to be part of

a phenomenon known as central sensitization (CS), leading to hyperalgesia

(increased pain intensity in response to a noxious stimulus) and allodynia

(pain in response to a non-painful stimulus), which exacerbate pain perception

[29].

Pain not only induces changes in neurons communicating

with the thalamus but also in neurons projecting from the amygdala to the

medial prefrontal cortex, related to cognitive and emotional processes [30].

Thus, the pain experience impacts not only the sensory-discriminative dimension

but also the affective-motivational dimension. Within this context, chronic

pain patients often exhibit pain catastrophizing, reduced self-efficacy, and

depression. Pain catastrophizing is defined as an exaggerated negative orientation

towards current or anticipated painful experiences, encompassing feelings of

helplessness related to pain, and is a risk factor for the development of

chronic pain [31].

Furthermore, a factor that can either positively or

negatively influence the pain experience is self-efficacy — the belief that one

can successfully perform a task or achieve a favorable outcome. Self-efficacy

is one of the main determinants of how a person with chronic pain will manage

their pain, potentially affecting their adherence to different forms of

treatment depending on its level [31]. Additionally, it is worth noting that

participant experience plays a crucial role in adherence to regular exercise;

thus, enjoyment is linked to greater participation and the effectiveness of

physical exercise, while unpleasant experiences negatively impact exercise

adherence and participation [32].

Moreover, studies indicate

that 40-50% of individuals with chronic pain also suffer from depression [33],

as chronic pain can be a stress factor that induces depression or exacerbates

the processes involved in the progression of the disease. Individuals who

develop both conditions simultaneously often face a poor prognosis [33].

Pain assessment

Conducting a detailed pain assessment is essential for

guiding professional conduct during pain treatment and for prescribing physical

exercise effectively, aiming to prevent the onset of pain during intervention.

To achieve this, it is crucial to select appropriate tools for assessing pain

based on the specific situation, as well as the specificity and information

each instrument provides [33]. Quantitative sensory testing (QST) can be

employed, which assigns numerical values to the observed phenomenon — in this

case, pain — using simple tools such as an algometer, a sphygmomanometer, and a

stopwatch. Among the tests highlighted in the literature are pressure pain

threshold (PPT), temporal summation (TS), conditioned pain modulation (CPM),

and tactile detection threshold (TDT). Together, these tests form a method for

assessing CS, which is commonly present in chronic pain patients [34].

Additionally, pain can be assessed using scales such as

the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS), the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), and the

Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), which are practical and quick to administer.

Questionnaires like the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), the Brief Pain

Inventory - Short Form (BPI-SF), and the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire

(PSEQ-10) can also be used to gather more detailed insights about the pain

experience.

The PPT assesses the minimum pressure applied to a body

area necessary to elicit a painful or uncomfortable sensation. This test

evaluates the nociceptive threshold of free nerve endings in the sensory

neurons located in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord [35]. Studies indicate

that individuals with chronic pain generally have a lower pain threshold

compared to healthy individuals, which can be considered a factor related to CS

[36] (Figure 1A). The PPT can be evaluated near the affected area or in a distant

region from the pain focus. For assessing PPT in the lumbar region, a digital

pressure algometer with a 1 cm² area is used, bilaterally 5 cm laterally from

the spinous processes of the third (L3) and fifth (L5) lumbar vertebrae [37].

Another measure of quantitative sensory testing is the TS

which assesses the excitability of type C fibers in the dorsal horn of the

spinal cord when painful stimulation is applied [38]. The main characteristic

of TS is the increase in pain perception with repeated painful stimulation

[39]. For this test, a persistent painful stimulus is applied using a pressure

algometer at a constant pressure of 4 kg/cm² on an area of the body, usually

the forearm or thenar region, for 30 seconds. During this period, pain

intensity is assessed at four different time points (1st, 10th, 20th, and 30th

seconds) using a numerical pain scale (0-10). Significant discrepancies in

values are an indicator that pain is summing in this individual rather than

habituating to the stimulus, a feature often present in populations with

chronic pain due to CS [40] (Figure 1B).

CPM is described as the phenomenon where "one pain

inhibits another pain". The CPM assesses the nervous system's ability to

reduce pain sensation when another painful stimulus is applied at a distant

site. When the pain control system functions correctly, the second painful

stimulus, known as the conditioning stimulus, reduces the pain of the first

painful stimulus [41]. It is worth noting that CPM and TS are complementary, as

they assess, respectively, the descending and ascending pain pathways.

To assess CPM, the PPT is first evaluated in a specific

area, possibly the same area where TS was assessed. A second painful stimulus

(conditioning) is applied at another location, which may involve pressure

(e.g., using a sphygmomanometer) or a thermal stimulus (e.g., cold water),

until the stimulus is perceived with an intensity greater than 4 on the NPRS.

During the application of the conditioning stimulus, the PPT is reassessed at

the same site evaluated earlier. Five minutes after the removal of the conditioning

stimulus, the PPT is reassessed [34]. An increase in PPT during the second and

third measurements indicates pain modulation reduction, suggesting that

descending pain pathways are activated and capable of decreasing pain intensity

(Figure 1C). For further guidance on performing these tests, access the video.

Figure 1 - 1A: Assessment of PPT, performed

bilaterally 5 cm from the spinous processes of L3 and L5. 1B: Assessment

of TS of pain in the dominant arm of the volunteer, 7.5 cm above the wrist

line. 1C: Evaluation of CPM, using ischemic compression as the

conditioned stimulus via a sphygmomanometer. The PPT was assessed at the same

location as the temporal summation, 7.5 cm above the wrist line

The TDT is used to identify signs of hyperalgesia and

allodynia, conditions commonly found in individuals with CS [42]. To perform

this test, a set of six monofilaments, all made of nylon and each with a

different diameter and weight, is used. The filaments progressively increase in

pressure applied to the skin. If a filament that does not normally induce pain

elicits a painful response in the individual, it is likely that the person has

allodynia. Furthermore, if one of the filaments used as a mild painful stimulus

induces a pain intensity greater than what is expected, this may be a sign of

hyperalgesia [43].

It is important to note that the performance of

quantitative sensory tests is done using devices such as a pressure algometer,

Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments, and a sphygmomanometer. These devices are

widely available for purchase by professionals, and they are generally more

affordable compared to other research equipment. An example of a device that

requires greater financial investment is the computerized pressure algometry.

The choice of equipment depends on the professional’s available budget and desired

investment, as both digital and computerized algometers provide reliable

evaluation results.

In addition to quantitative sensory testing, pain can be

assessed using the NPRS and the VAS, both of which evaluate an individual’s

subjective pain perception [44]. For the NPRS, a ruler divided into eleven

equal parts (ranging from zero to ten) is used, where the patient matches their

pain intensity to a corresponding number, with zero representing no pain and

ten representing the maximum pain [45]. The VAS is similar but does not involve

specific numbers; instead, the patient is asked to mark a point on a 10 cm

line, where 0 represents no pain and 10 represents the worst possible pain. A

ruler is then used to measure the exact point marked by the patient [46]. Both

scales are easy to understand and require minimal resources for use. These

tools allow for an understanding of pain intensity in an individual and can be

used to assess pain tolerance during exercise, as well as monitor progress over

time for those being evaluated [46].

Pain scales and their variations have been validated in

Brazil for use in various populations [46]. For example, the VAS gave rise to

the Faces Pain Scale, which is used to improve understanding for specific

populations, such as children, adolescents, older people, people with hearing

impairments, and aphasic individuals. When used with children, the scale

includes drawings of characters from well-known programs [47]. For older

people, adaptations are also made using concepts that are easier to understand

in cases of cognitive impairment related to aging [48]. Figure 2 shows the

variations of pain scales.

Figure 2 - Pain scales

Another way to assess individuals suffering from pain is

through questionnaires, which can be directly related to pain or psychosocial

problems associated with the chronicity of pain. A well-known questionnaire for

pain assessment is the MPQ, which focuses on the context and characterization

of pain, addressing sensory and affective aspects. This questionnaire has a

broad range of application and can be used for both chronic and acute pain in

various conditions where pain is a symptom [49]. The MPQ is subdivided into

four subscales that assess the sensory, affective/evaluative, and miscellaneous

aspects of pain. Responses are given on a scale from: (0) none, (1) mild, (2)

discomforting, (3) distressing, (4) horrible, and (5) excruciating [50].

Similar to the MPQ, the pain severity subscale of the

BPI-SF directly assesses the interference and intensity of pain and can also be

used in various situations. It consists of four 11-point numeric pain scales:

two assess the worst and least pain experienced in the last 24 hours, and the

other two assess the average and current pain at the time of the evaluation

[51].

Another questionnaire that can be used is the Central

Sensitization Inventory (CSI), which indicates the presence of symptoms

associated with CS through a self-perception scale. In this context, other

factors related to CS, such as catastrophizing and self-efficacy, can also be

assessed through the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) and the PSEQ-10,

respectively. It is important to note that these latter measures enable a

psychosocial evaluation of this population [52].

Furthermore, when discussing pain, another important

factor that is highly affected in this population is quality of life. Quality

of life can be assessed using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)

questionnaire, which evaluates the quality of life across five dimensions:

mobility, self-care, usual activities, anxiety/depression, and pain/discomfort.

The last dimension specifically evaluates the impact of pain on quality of

life. EQ-5D results can be classified according to the severity level [53].

Additionally, there are specific questionnaires for evaluating the quality of

life in individuals with chronic pain, such as the Short Form Health Survey 36

(SF-36), which assesses the multidimensional aspects of pain’s impact on this

population [53].

Thus, we believe that the use of these tests, scales, and

questionnaires provides a comprehensive view of the health status of the

individual being assessed, helping to guide the treatment plan and track the

progress of the patient/client beyond commonly known aspects such as strength,

hypertrophy, and range of motion. The evolution of pain and how it affects

other socioemotional domains is an important aspect to monitor, as it

significantly contributes to the well-being and quality of life of individuals.

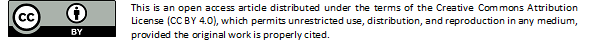

Table I summarizes the main instruments used for pain assessment by movement

professionals.

Table I - Pain assessment instruments

PPT = pressure pain threshold; TS = temporal summation;

CPM = conditioned pain modulation; TDT = tactile detection threshold; NPRS =

Numerical Pain Rating Scale; VAS = visual analog scale; PCS = pain

catastrophizing scale; MPQ = McGill pain questionnaire; BPI-SF = brief pain

inventory – short form. PSEQ-10 = pain self-efficacy questionnaire

Final considerations

Pain assessment by movement professionals is highly

valuable in clinical and practical contexts, including gyms, studios, and

clinics, as individuals in these settings are often afflicted by pain, whether

chronic or acute. Understanding the importance of pain assessment, the tools

available, and their proper application enables professionals to conduct

thorough evaluations and prevent pain from hindering clients' performance when

pain is not the treatment focus. This can help shift the perspective, viewing exercise

not as something that causes pain, but as something that reduces it.

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this

article was reported

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Coordination for

the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel, Brazil-CAPES. The funding source

had no involvement in the conduct of the study or in the preparation of the

article for publication

Author contributions

Conception and design of the

research: Da Silva-Grigoletto

ME, Santos PJ; Acquisition of data: Barbosa LFV; Writing

of the manuscript:

Barbosa LFV, Santos PJ, Aragão-Santos JC, Pereira-Monteiro MR; Critical revision of the manuscript

for important intellectual content: Da Silva-Grigoletto

ME

Glossary

Hypoalgesia - Reduction in sensitivity to pain.

Hyperalgesia - Increased sensitivity to pain.

Noxious stimuli - Stimuli that have the

potential to cause tissue damage or

evoke the sensation of pain.

Nociceptors - Sensory receptors located in the skin that are

specialized in detecting noxious stimuli and transmitting pain signals to the

central nervous system.

Myelinated - Refers to nerve fibers that are surrounded by a myelin

sheath, which increases the speed of nerve signal transmission.

Unmyelinated - Nerve fibers that lack a myelin sheath, resulting in

slower transmission of nerve signals.

Temporal summation - A process in which repetitive and continuous stimuli

gradually increase the perception of pain, even if the stimulus itself does not

intensify.

Central sensitization - Increased responsiveness of neurons in the central

nervous system following repetitive or intense stimulation, leading to an

exaggerated perception of pain.

Allodynia - Pain caused by stimuli that do not normally provoke

pain, such as light touch on the skin.

Sensory-discriminative dimension - The aspect of pain experience that allows for

identification of the location, intensity, and type of the painful stimulus.

Affective-motivational dimension - The aspect of pain experience related to the emotional

and motivational responses it triggers, such as distress or the desire to avoid

pain.

References

- DeSantana JM, Perissinotti

DM, Oliveira Junior JO, Correia LM, Oliveira CM e Fonseca PR. Definition of pain

revised after four decades. BrJP. 2020;3(3):197-8. doi: 10.5935/2595-0118.20200191 [Crossref]

- Latina R, Sansoni J, D’Angelo D, Di Biagio E, De Marinis MG e Tarsitani, G. Etiology and prevalence of chronic pain

in adults: a narrative

review. Professioni Infermieristiche.

2013;66(3):151–58. doi: 10.7429/pi.2013.663151 [Crossref]

- Aguiar DP, Souza CPQ,

Barbosa WJM, Santos Júnior FFU, Oliveira AS. Prevalence of

chronic pain in Brazil: systematic review. BrJP. 2021;4(3):257-67. doi: 10.5935/2595-0118.20210041 [Crossref]

- Patel AS, Farquharson R, Carroll D, Moore A, Phillips CJ, Taylor RS, et al. . The impact

and burden of chronic pain in the workplace: a qualitative systematic review.

Pain Practice, 2012;12(7):578–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00547.x [Crossref]

- Racine M. Chronic pain and suicide risk: a comprehensive review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87;269–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.08.020 [Crossref]

- Liang Z, Tian S, Wang C, Zhang M, Guo H, Yu Y, et al. The best exercise modality and dose for reducing pain in adults with low back pain: a systematic review with model based Bayesian Network Meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2024;54(5):315-27. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2024.12153 [Crossref]

- Alves RC, Tavares JP, Funes RAC, Gasparetto GAR, Silva KCC, Ueda TK. Análise do conhecimento sobre dor pelos acadêmicos do curso de fisioterapia em centro universitário. Revista Dor. 2013;14(4):272–79. doi: 10.1590/S1806-00132013000400008 [Crossref]

- Silva AC e Ferreira J. Corpos no ‘limite’ e risco à saúde na musculação: etnografia sobre dores agudas e crônicas”. Interface - Comunicação, Saúde, Educação. 2017;21(60):141–51. doi: 10.1590/1807-57622015.0522 [Crossref]

- Meeus M, Hermans L, Ickmans K, et al. Endogenous pain modulation in response to exercise in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and comorbid fibromyalgia, and healthy controls: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Pain Pract. 2015;15(2):98-106. doi: 10.1111/papr.12181 [Crossref]

- Naugle KM, Fillingim RB, Riley JL. A meta-analytic review of the hypoalgesic effects of exercise. J Pain. 2012;13(12):1139-1150. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.09.006 [Crossref]

- Oliveira MAS, Fernandes RSC, Daher SS. Impact of exercise on chronic pain. Rev Bras Med Sport. 2014;20(3):200-203. doi: 10.1590/1517-86922014200301415 [Crossref]

- Bottega FH e Fontana RT. A dor como quinto

sinal vital: utilização da escala de avaliação por enfermeiros de um hospital

geral. Texto & Contexto Enfermagem. 2010;19(2):283–90.

https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=71416097009

- Borges PA, Koerich MHAL, Wengerkievicz KC, Knabben RJ. Barreiras e facilitadores para adesão à prática de exercícios por pessoas com dor crônica na Atenção Primária à Saúde: estudo qualitativo. Physis: Revista de Saúde Coletiva. 2023;33:e33019. doi: 10.1590/s0103-7331202333019 [Crossref]

- Medeiros JD e Pinto APS.

Impacto social e econômico na qualidade de vida dos indivíduos com lombalgia:

revisão sistemática. Caderno de Graduação - Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde.

2014;2(1):73–78. https://periodicos.set.edu.br/fitsbiosaude/article/view/1037

- Borisovskaya A, Chmelik E e Karnik A. Exercise and chronic pain. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2020;1228:233–53. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-1792-1_16 [Crossref]

- Polaski AM, Phelps AL, Kostek MC, Szucs KA, Kolber BJ. Exercise-induced hypoalgesia: a meta-analysis of exercise dosing for the treatment of chronic pain. Plos One. 2019;14(1):e0210418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210418 [Crossref]

- Souza RFC e Pereira Júnior

AA. Prevalência de dor lombar em praticantes de musculação. Revista da UNIFEBE.

2010;1(8):190–98.

https://periodicos.unifebe.edu.br/index.php/RevistaUnifebe/article/view/549

- Cardoso M. e Rosas RF.

Presença de dor em praticantes de exercício físico em academia nas diferentes

modalidades. Repositorio Unesc.net. 2012.

http://repositorio.unesc.net/handle/1/956

- Freire VHJ, Almeida BR, Barros RC, Soares ACN, Ribas IGC, Sá FAF. Caracterização da dor em praticantes profissionais e amadores de jiu-jitsu. Revista Eletrônica Acervo Saúde. 2023;23(10):e13888. doi: 10.25248/reas.e13888.2023 [Crossref]

- Buzetti LC, Silva VF, Ferreira GLA, Lima JÁ, Batista SO, Moretti VB, et al. Prevalência e local de dor em praticantes de crossfit em uma cidade do sul de minas gerais. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2023;29:e2021_0328. doi: 10.1590/1517-8692202329022021_0328p [Crossref]

- Boron, W. F. Fisiologia médica. 2 ed. Rio de

Janeiro: 2015.

- Aires MM. Fisiologia. 4 ed.

Rio de Janeiro: 2012.

- Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, Julius D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell. 2009;139:267–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.028 [Crossref]

- Lee GI, Neumeister MW. Pain. Clin Plast Surg. 2020;47:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2019.11.001 [Crossref]

- Martin E. Pathophysiology of pain. Pain Management in Older Adults, Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018: p.7–29. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-71694-7_2 [Crossref]

- Ossipov MH, Morimura K, Porreca F. Descending pain modulation and chronification of pain. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2014;8:143–51. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000055 [Crossref]

- Nir R-R, Yarnitsky D. Conditioned pain modulation. Current Opinion in Supportive & Palliative Care 2015;9:131–7. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000126 [Crossref]

- Meeus M, Nijs J. Central sensitization: a biopsychosocial explanation for chronic widespread pain in patients with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:465–73. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0433-9 [Crossref]

- Lumley MA, Cohen JL, Borszcz GS, Cano A, Radcliffe AM, Porter LS, et al. Pain and Emotion: A Biopsychosocial Review of Recent Research. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67:942–68. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20816 [Crossref]

- Edwards RR, Dworkin RH, Sullivan MD, Turk D, Wasan AD. The role of psychosocial processes in the development and maintenance of chronic pain disorders. J Pain. 2016;17:T70–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.01.001 [Crossref]

- Sheng J, Liu S, Wang Y, Cui R, Zhang X. The Link between depression and chronic pain: neural mechanisms in the brain. Neural Plast. 2017;2017:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2017/9724371 [Crossref]

- Collado-Mateo D, Lavín-Perez AM, Penacoba C, Del Coso J, Leyton-Román M, Luque-Casado A, et al. Key Factors associated with adherence to physical exercise in patients with chronic diseases and older adults: an umbrella review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4);2023. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18042023 [Crossref]

- Dansie EJ, Turk DC. Assessment of patients with chronic pain. Br J Anaesth 2013;111:19–25. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet124 [Crossref]

- Leite PMS, Mendonça ARC, Maciel LYS, Poderoso-Neto ML, Araujo CCA, Góis HCJ, et al. Does electroacupuncture treatment reduce pain and change quantitative sensory testing responses in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain? a randomized controlled clinical trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;2018:e8586746. doi: 10.1155/2018/8586746 [Crossref]

- Stein C. Opioid receptors. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:433-51.

https://doi:10.1146/annurev-med-062613-093100 [Crossref]

- Amiri M. Alavinia M, Singh M e Kumbhare D. Pressure pain threshold in patients with chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 202:100(7):656. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001603 [Crossref]

- Corrêa JB, Costa LO, Oliveira NT, Sluka KA e Liebano RE. Central sensitization and changes in conditioned pain modulation in people with chronic nonspecific low back pain: A case-control study. Exp Brain Res. 2015;233(8):2391–99. doi: 10.1007/s00221-015-4309-6 [Crossref]

- Staud R, Crass JG, Robinson ME, Peristen WM, Price DD. Atividade cerebral relacionada à soma

temporal da dor evocada pela fibra C. Dor. 2007;129:130–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.010 [Crossref]

- Koltyn KF, Knauf MT e Brellenthin AG. Temporal summation of heat pain modulated by isometric exercise. Eur J Pain. 2013;17(7): 1005–1011. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00264.x [Crossref]

- Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011;152:S2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030 [Crossref]

- Kennedy DL, Kemp HI, Wu C, Ridout DA e Rice ASC.Determining real change in conditioned pain modulation: A repeated measures study in healthy volunteers. J Pain. 2020;21(5-6):708–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.09.010 [Crossref]

- Ji R-R, Nackley A, Huh Y, Terrando N, Maixner W. Neuroinflammation and central sensitization in chronic and widespread pain. Anesthesiology. 2018;129:343–66. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002130 [Crossref]

- Sydney PBH, Conti PCR. Diretrizes para avaliação somatossensorial em pacientes portadores de disfunção temporomandibular e dor orofacial. Rev Dor. 2011;12:349–53. doi: 10.1590/S1806-00132011000400012 [Crossref]

- Pimenta CAM. Escalas de

avaliação de dor. In: Teixeira MD (ed.) Dor conceitos gerais. São Paulo: Limay. 1994;46-56.

https://repositorio.usp.br/item/000882788

- Chiarotto A, Maxwell LJ, Ostelo RW, Boers M, Tugwell P, Terwee CB. Measurement properties of visual analogue scale, numeric rating scale, and pain severity subscale of the brief pain inventory in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2019;20:245–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.07.009 [Crossref]

- Shafshak TS, Elnemr R. The visual analogue scale versus numerical rating scale in measuring pain severity and predicting disability in low back pain. J Clin Rheumatol. 2021;27:282–5. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000001320 [Crossref]

- Tsze DS, von Baeyer CL, Bulloch B, Dayan PS. Validation of self-report pain scales in children. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e971–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1509 [Crossref]

- Pereira LV, Pereira GDA, Moura LAD, Fernandes RR. Pain intensity among institutionalized elderly: a comparison between numerical scales and verbal descriptors. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2015;49:804–10. doi: 10.1590/S0080-623420150000500014 [Crossref]

- Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63Suppl 11:240-252. doi: 10.1002/acr.20543 [Crossref]

- Escalante A, Lichtenstein MJ, White K, Rios N, Hazuda HP. A method for scoring the pain map of the McGill pain questionnaire for use in epidemiologic studies. Aging Clin Exp Res. 1995;7(5):358–66. doi: 10.1007/BF03324346 [Crossref]

- Chiarotto A, Maxwell LJ, Ostelo RW, Boers M, Tugwell P, Terwee CB. Measurement properties of visual analogue scale, numeric rating scale, and pain severity subscale of the brief pain inventory in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2019;20:245–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.07.009 [Crossref]

- Bonafé FSS, Marôco J, Campos JADB. Questionário de autoeficácia relacionado à dor e seu uso em amostra com diferentes durações de ocorrência de dor. BrJP. 2018;1(1):33–9. doi: 10.5935/2595-0118.20180008 [Crossref]

- Robinson CL, Phung A, Dominguez M, Remotti E, Ricciardelli R, Momah DU, et al. Pain scales: what are they and what do they mean. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2024;28(1):11–25. doi: 10.1007/s11916-023-01195-2 [Crossref]